Copyright Cable News Network

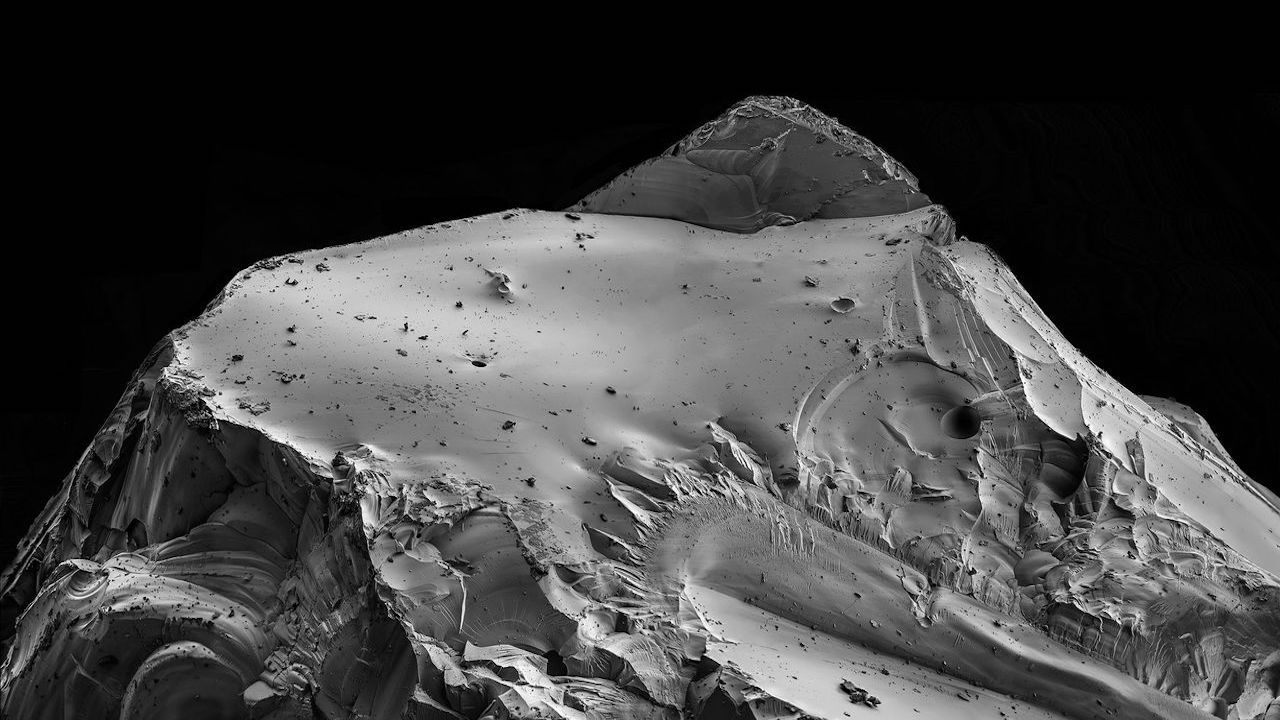

Off Brazil’s northeastern coast, where the sediment-heavy water of the vast Amazon River tips out into the Atlantic, are two very different types of treasure. The first is an ecological gem: a 3,600 square-mile deepwater coral reef discovered less than a decade ago. The second treasure puts the first in immediate danger. Billions of barrels of oil may lie in the ancient sediments beneath the seabed, and licenses have just been approved to drill there. A few hundred miles north, off the coast of Guyana, companies are already pumping around 650,000 barrels of oil a day from a huge deep-water reservoir discovered in 2015. The find has transformed this rainforest-carpeted country into the planet’s newest petrostate and highest oil producer per capita. Several thousand miles inland to the south, the wide, dusty plains of western Argentina’s Vaca Muerta — “dead cow” in English — are dotted with oil wells. Fossil fuel production from this enormous shale deposit has boomed over the past decade, putting it on track to produce more than a million barrels a day by 2030, analysts predict. Welcome to South America’s new oil frontier. “It’s really incredible how fast and how much it’s expanding,” said Nicole Figueiredo de Oliveira, the executive director at environmental non-profit Arayara. Countries across the region are ramping up extraction but Brazil, Guyana and Argentina are at the forefront — among the top five drivers of global oil growth outside of OPEC, the group of major oil exporters. They are three very different countries: an economic behemoth with an environment-championing president, a biodiversity hotspot with high rates of poverty and an economically volatile country led by a chainsaw-wielding climate denier. Yet they are united in their quest to expand oil production, arguing it’s vital to their economic and social development. This new fossil fuel boom is happening just as the impacts of the climate crisis — driven by fossil fuels — are beginning to bite in ever more alarming ways. People in South America are dying in fires, floods, storms and droughts made longer and more catastrophic by climate change. Brazil’s role as host of the COP30 climate conference, which is supposed to be a landmark summit where countries set out goals to radically reduce planet-heating pollution, adds a particular dissonance to this oil surge. But as global oil demand stays strong, and other, richer, countries show few signs of scaling back, their argument is: Why shouldn’t oil supply come from South America? The continent has a long history of fossil fuel extraction; it holds the second-largest reserves of oil and gas after the Middle East. Yet it’s one of the few regions that didn’t take advantage of the oil boom at the beginning of this century due to political riskiness and an aversion to private investment, said Francisco Monaldi, director of the Latin America Energy Program at Rice University. “But that is changing very significantly,” he told CNN. Recent discoveries have stirred excitement, especially as the oil in South America is typically cheaper than average — deepwater sources, in particular, tend to produce large amounts at lower cost — and it also tends emit slightly lower levels of climate pollution per barrel, as it often requires less processing and is produced using newer infrastructure and cleaner energy. Huge oil companies including Exxon and Chevron have plowed in, seeing dollar signs in South America’s deep oceans and shale fields just as the US shale boom starts to plateau. Brazil is a superstar: the region’s largest oil and gas producer. Production has “reached levels that have never been seen in the region,” Monaldi said. This is in large part due to ultra-deep “pre-salt” oil reserves discovered in 2006 buried under thick layers of ancient salt beneath the ocean. Crude oil became the country’s top export in 2024 for the first time, overtaking soybeans, and there are hopes production will ramp up much further. In August, BP announced it had made its largest oil and gas discovery in 25 years off the coast of Rio de Janeiro. Farther south, near Uruguay, oil companies hope the Pelotas Basin could be another new frontier. Perhaps the most controversial project is the one at the mouth of the Amazon River — the Foz do Amazonas basin — part of what’s known as the “Equatorial Margin,” a stretch of ocean along the northern coast of Brazil. In June, Brazil auctioned off several offshore oil blocks in the region, 19 of which are in the Amazon Basin, to companies including Chevron, Exxon and Brazil’s state-run oil company Petrobras. Petrobras has been trying to drill here for many years. In 2023, Brazil’s environmental agency IBAMA denied it an offshore drilling license, citing environmental concerns. But last month, the agency gave the greenlight for exploratory drilling “after a rigorous environmental licensing process,” according to a statement from IBAMA. The agency’s task was to assess the “technical feasibility” of the project only, not the political or strategic side of oil exploitation, said a spokesperson for Brazil’s Ministry of Environment and Climate Change, which oversees IBAMA. Any process involving high-risk areas such as the Foz do Amazonas “must comply with the strictest technical, scientific, and environmental standards,” they added. The decision “is an achievement of Brazilian society,” said Magda Chambriard, president of Petrobras, in a statement. Environmental advocates are strongly opposed, arguing drilling in this ecologically delicate swath of ocean, with its unique reefs and huge stretches of mangrove forests, could bring catastrophic consequences. Ultra-deep water and strong currents mean any oil spill could quickly be swept across miles of ocean and coastline, and the remoteness of the drilling location from large settlements could delay clean-up operations, said Arayara’s Figueiredo de Oliveira. Approving drilling here mere weeks before the start of COP30 in the city of Belém — known as the gateway to the Amazon — presents tricky optics for Brazil, which is trying to walk a tightrope between environmental champion and fossil fuel power. The country’s mighty rivers and abundant rains mean most of its electricity comes from clean hydroelectric power. Brazil’s president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, has presided over a sharp decline in deforestation and an increase in renewables. But Lula has always been pro-oil, Figueiredo de Oliveira said. He greeted Brazil’s big pre-salt discovery, made during his previous presidential term, with the words, “God is Brazilian.” A famous photo shows him raising oil-drenched hands at a Petrobras event in 2010. Lula has firmly rejected claims of hypocrisy. “I don’t want to be an environmental leader. I never claimed to be,” he said at a COP30 meeting last week, adding it would be “irresponsible,” to quit oil. He argues oil wealth can help fund Brazil’s clean energy transition, although some fear the quest to become a major oil power will only delay it. “Every new discovery does set back the effort to move the world off fossil fuels; there’s a loss of momentum,” said Michael Ross, a political science professor at the University of California, Los Angeles. Perhaps Lula’s main narrative is that oil revenues will provide a route to development and a pathway out of poverty, especially for the country’s poorer Amazon states. But Brazil is already a powerhouse “with many other economic opportunities,” Ross told CNN. The argument oil is vital for development may be easier to make in a country like Guyana, where around 48% live on less than $5.50 a day, according to the World Bank. Guyana, which has a similar geology to Brazil’s Equatorial Margin, is experiencing a remarkable oil boom. The 2015 offshore discovery “represents one of the most transformative milestones” in the country’s modern history, said President Irfaan Ali. It has transformed the nation of around 820,000 people into the world’s fastest expanding economy. “We have never seen a country produce so many barrels per capita in the history of (the region)… they belong now in the category of the countries of the Middle East,” Monaldi said. The government has insisted it can balance oil exploitation with environmental priorities. Guyana is one of the few countries that stores more planet-heating pollution than it produces due to its vast rainforests. It also says that revenues will boost socioeconomic growth. “We do not see a contradiction between the responsible development of our oil and gas sector and our commitment to protecting the planet’s climate,” Ali told CNN. Both are “integral parts of a single national mission” to cut poverty, boost the economy and protect the environment, he said. But there are concerns Guyana could fall victim to the “resource curse,” in which huge windfalls can make life worse for those who live there. Venezuela, for example, holds the world’s largest proven oil reserves, and has descended into authoritarianism and economic crisis. Ali insists the resource curse “is not destiny” and oil wealth will translate into “benefits for every household.” Yet some residents say they face sky- high living costs they blame on oil development, and the country’s health outcomes remain below the regional average, according to the World Bank. South American oil is not just about deep water. Argentina’s huge shale region, Vaca Muerta, often compared to the Permian Basin in Texas, holds the world’s second largest reserves of shale gas and fourth largest of shale oil. It’s Argentina’s big hope for economic recovery under libertarian President Javier Milei. “Almost everything is about expanding Vaca Muerta,” said Gabriel Blanco, a professor in the Faculty of Engineering at the National University of Central Buenos Aires and former national director of climate change in Argentina. Oil and gas are a very easy sell domestically, Blanco told CNN. Climate change has “never ever” been on the public or political agenda, he said. Instead, “the narrative says that we are going to be rich and we’re going to develop.” Vaca Muerta is an attractive proposition for fossil fuel companies. Shale is a very different type of investment than deep-water drilling, Monaldi said. Companies can spend relatively small amounts to see if they can recover their money before putting in more. This encourages investment in Argentina, a country with “high political and regulatory risk,” he said. But environmental experts fear the impacts of this booming shale field. Fossil fuels are extracted by “fracking,” a process that involves drilling into the Earth and injecting fluids at high pressure. “They use a lot of water, they use a lot of sand and chemicals, and so it’s a mess,” Blanco said. Exactly how South America’s oil future will unfold is not yet clear. New discoveries in Brazil may turn out to be less viable than hoped. For projects already drilling and pumping, reserves often run out earlier than anticipated, UCLA’s Ross said. Oil demand is also predicted to peak at the start of the next decade, which could mean countries that go hard on fossil fuels will find themselves locked into an unprofitable industry. “These countries are getting to the party right as the bar is closing,” Ross said. For now, however, demand remains. “While there’s still a gap between current production and demand, there will be investment into new projects,” said Flávio Ferreira Menten, an analyst at the research firm Rystad Energy. There are geopolitical considerations, too. If US oil production doesn’t keep growing, South America “becomes much more important,” Monaldi said, otherwise the world risks becoming reliant on countries such as Saudi Arabia and Russia. What’s happening in South America is reflective of something bigger, according to Blanco. The region’s love affair with fossil fuels is part of a global movement, he said: an implicit — and sometimes explicit — consensus that oil exploitation can and should continue for decades to come even in the face of a barreling climate crisis. “It seems like leaders decided to step strongly on the on the gas pedal and move forward with fossil fuels everywhere,” he said, “no matter what.”