By Bruce Dorminey,Mark Sennet,Senior Contributor

Copyright forbes

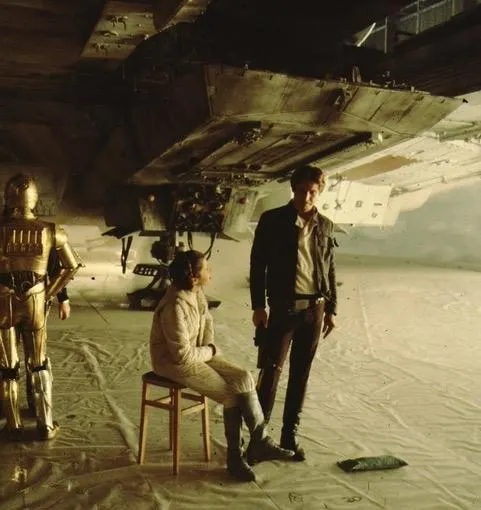

Actors Harrison Ford, Carrie Fisher, and Anthony Daniels as C-3PO pose for a portrait on the set of Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back in 1979 in London, England. (Photo by Mark Sennet/Getty Images)

Getty Images

As the recent Worldcon 2025 Convention here in Seattle reaffirmed, science fiction is more than just a genre of contemporary literature. It remains a real-world driver that inspired a surprising number of researchers to make the leap to astronomers, aerospace engineers, astrobiologists, even astronauts.

But does science fiction drive science or does science drive science fiction?

Science fiction drives science in the sense of creating inspiration and interest in science and fostering curiosity and the ability to ask questions, Julie Novakova, a Czech evolutionary biologist, science fiction author, editor and translator, tells me during Worldcon. But mostly science drives science fiction because science fiction authors often use inspiration from modern day science and discoveries to craft their stories, she tells me.

For more than 200 years, science fiction has been a part of global culture, now sometimes called speculative fiction. It owes some of its roots to Karel Capek, a little-known Czech journalist turned author and playwright, who with inspiration from his brother, Josef, first coined the term robot a century ago.

The word robot comes from the Czech word ‘robota’ which meant involuntary servitude, something very close to slavery, says Novakova.

The word ‘robot’ spread into every vestige of the world as we know it, Novakova writes in “From the Land of Robots and Golems” — a collection of stories from various authors in which Novakova edited, translated and even contributed. While it first appeared in Capek’s 1920 drama R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots), the concept of robots had already been a familiar one in Czech-region speculative fiction, because golems, clay servants originating from Jewish folklore, [were]

remarkably similar to robots in many ways, she writes.

Robots In Revolt

In his 1920 play, Capek’s robots end up revolting against humanity. But this idea of AI revolting against humanity was preceded by Mary Shelley’s classic 1818 novel “Frankenstein.” Arguably, the first science fiction horror tale of AI gone horribly wrong, the novel continues to evoke fear that human meddling in methods of reanimation and/or advanced intelligence will boomerang back to haunt us in real life ways that the monster Frankenstein never could.

MORE FOR YOU

Shelley’s “Frankenstein,” widely considered to be the founding work of modern-day science fiction, reflected the early 19th century fears of science and of artificial machines and possibly artificial life and even electricity, says Novakova.

But Shelley’s masterwork preceded the late 19th century boon in science fiction, including H.G. Wells’ two classic novels “The War of the Worlds” and “The Time Machine” by almost a century. Thus, what about Czech culture fostered the idea of robots and the growth of science fiction?

During the first big wave of Czech science fiction, after World War I, Czechoslovakia became very prosperous and gained independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, says Novakova. And there was huge interest in science and technology and literature reflected that, she says.

As for today? Science fiction is still preoccupied with real world fears about the pitfalls and potential dangers of AI.

If we feed AI rubbish, it can turn out pretty bad, as we have seen in the examples of countless chatbots which developed in very bad ways, says Novakova. But, in fiction, we have also seen many examples of amicable robots, or androids like Star Wars’ C-3PO and there are also robots who care for the elderly or small children, she says. But we should make sure that we are using data we want AI to learn, says Novakova.

Yet is most science fiction space-based?

That’s really a huge segment of science fiction, but there is a lot of near future science fiction dealing with themes like the impacts of climate change and how we might mitigate them, says Novakova.

Is Novakova disappointed that we haven’t fully exploited our potential in space?

We should have had a permanent human research station on the Moon by now, says Novakova. But I am also in awe of what we have accomplished because fifty years ago, nobody imagined that we would have confirmed the detection of thousands of planets orbiting other stars, she says.

As for the science fiction genre itself?

As Novakova notes in her introduction to “From the Land of Robots and Golem,” although publishing might undergo massive shifts, the thirst for good stories will, hopefully, stay. It’s what has been at the core of legends told by the fire and tales whispered before sleep, she writes.

“From the Land of Robots and Golem”

Nova Vina Prague

A Malevolent Computer

Yet it would be hard to have a serious conversation about science fiction without referencing Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 film adaptation of Arthur C. Clarke’s classic novel “2001: A Space Odyssey.” The film revisits this age-old idea of technology gone wrong; in this case, in the form of the Discovery One spacecraft’s primary computer — the HAL 9000.

Flash forward to Kubrick’s haunting final act when astronaut Dave Bowman is ensconced, spacesuit in tow, in a bizarre, futuristic rococo hotel suite.

Bowman’s alien hosts never show themselves directly. But they do give the astronaut a taste of his future old age before the film ends with the classic shot of (depending on your interpretation) his transformation into a star child peering down onto Earth itself.

What does it all mean?

Frankly, I like the book more than the movie, says Novakova. But for me, “2001” represents humanity still in its Earth cradle; hopefully, at the beginning of its journey elsewhere, she says.

Forbes5 Little-Known Nuggets From Kubrick And Clarke’s ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’By Bruce Dorminey

Editorial StandardsReprints & Permissions