Copyright thediplomat

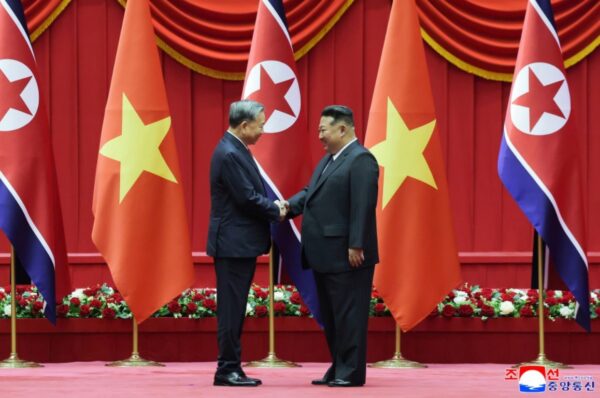

Despite successive rounds of sanctions, North Korea continues to generate hard currency and preserve diplomatic access. This persistence stems less from loopholes than from a “small-node strategy”: dispersing revenue and embedding low-visibility networks across jurisdictions where hedging and procedural multilateralism dominate. China and Russia are often blamed for enabling North Korea’s illicit finance. Yet Pyongyang has long turned to Southeast Asia for its permissive financial niches, historical ties to socialist states, and sustained diplomatic presence. Vietnam is a revealing case. Its “bamboo diplomacy” – firm in aims yet flexible in practice – anchors diversified ties with major powers and embeds Hanoi in ASEAN’s process-heavy forums. This posture safeguards autonomy but also creates gray zones that sanctioned actors can test. The 2024 lapse of the United Nations Panel of Experts (PoE) widened those gray zones by shifting enforcement to uneven national efforts. In this environment, North Korea’s use of labor, hospitality, information-technology (IT) services, maritime practices, and regional forums shows how low-visibility cash streams persist by riding on durable process cover. North Korean Party General Secretary and national leader Kim Jong Un’s 2019 state visit to Hanoi, where he met then-Vietnamese Party General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong, signaled interest in Vietnam’s reform model and helped institutionalize narrow channels of engagement that offered limited space within ASEAN’s architecture. During his October 2025 visit to Pyongyang, Vietnamese Communist Party General Secretary To Lam offered to share Vietnam’s “economic renovation” experience, to which Kim expressed interest in “national development” – continuing a dialogue begun six years earlier. Small-Node Strategy The small-node strategy is best understood as risk spreading. Rather than relying on a few large conduits vulnerable to disruption, North Korea cultivates a web of routine, low-visibility touchpoints that appear marginal in isolation but collectively sustain its external reach. These include hospitality businesses, freelance IT contracts, small trading houses, freight forwarding services, and commercial activity linked to diplomatic missions. Each node is easily overlooked, yet its aggregate effect is significant. Three dynamics reinforce this approach. By dispersing revenue and procurement across many small channels, Pyongyang reduces the risk that the loss of any single node will cripple its operations. The use of proxies, nominee directors, intermediaries, and reflagged assets obscures beneficial ownership and complicates attribution. And the slow, process-driven nature of regional institutions creates delays between suspicion and enforcement – delays Pyongyang exploits. Southeast Asia is especially fertile ground. Bureaucracies prioritize stability, services sectors remain cash-intensive, and legal systems favor gradualism. The 2024 PoE lapse amplified these tendencies by shifting oversight to uneven national and private efforts. In this environment, small nodes thrive, sustaining Pyongyang’s financial resilience and diplomatic space amid sanctions. Shifting Sanctions Landscape Between 2017 and 2019, the United Nations ratcheted up sanctions on North Korea, culminating in Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 2397, which capped refined-petroleum imports and required repatriation of overseas workers by late 2019 – a direct squeeze on Pyongyang’s cash and logistics. In March 2024, however, Russia vetoed the renewal of the PoE, and the mandate lapsed on April 30 that year. Sanctions remain, but centralized monitoring collapsed, fracturing enforcement across uneven national authorities, ad hoc coalitions, and private open-source efforts. This diffusion of oversight matters. As King Mallory notes, North Korea’s sanctions evasion clusters around four streams: hard-currency generation, procurement, covert transportation, and covert finance – enabled by officials, workers, shell firms, and intermediaries. Eleven like-minded nations launched the Multilateral Sanctions Monitoring Group in October 2024 to help close the gap, but concerns remain about legitimacy and reach. The result is fragmented oversight with uneven deterrence – exactly the environment in which the small-node strategy thrives, amplifying cover opportunities more than financial returns. In Vietnam, the post-PoE environment produces compliance lags and jurisdiction shopping, pushing enforcement onto complex tasks like know-your-customer vetting, maritime analytics, and platform policing. North Korea’s Evasion Pathways in Vietnam North Korea’s illicit financial activities in or through Vietnam have ranged from ship-to-ship transfers and restaurant operations to trade and IT labor exports. The best-known cases of sanctions violations trace back to the Workers’ Party’s Munitions Industry Department (MID), which oversees nuclear and missile programs. In 2019, the U.S. Treasury sanctioned MID agent Kim Su Il for exporting coal and chartering ships for transport – activities that continued in Vietnam until at least August 2019 via the Korea Puhung Trading Company. In 2025, the Treasury sanctioned Kim Se Un for running fraudulent overseas IT-worker schemes and converting proceeds into cryptocurrency through a Vietnam-based subsidiary of Korea Sobaeksu Trading Company, another MID front. These cases show that Pyongyang views Vietnam as a favorable environment for proliferation financing. Kim Su Il’s operations continued well beyond UNSCR 2371’s 2017 coal ban, while Kim Se Un’s sanctioning in 2025 demonstrated the MID’s continued regional reach. This persistence suggests either cautious enforcement shaped by historical ties or limited institutional capacity. To Lam’s 2025 visit to Pyongyang reinforced this duality. Vietnam remains one of the few countries where North Korea still operates embassy-linked restaurants and limited tourism ventures that generate foreign currency. North Korea is also suspected of routing coal and software sales through Vietnam. Although Hanoi formally supports U.N. sanctions, its gradualist governance and dense commercial ecosystem create precisely the gray zones in which small-node activity operates. Vietnam’s weaknesses in countering money laundering, terrorist financing, and proliferation financing – combined with an expanding cryptocurrency market – have been identified as creating opportunities for illicit activity. These conditions reveal structural vulnerability rather than intent. For Pyongyang, they represent opportunity. Understanding why Pyongyang continues to invest diplomatic capital in the Vietnam channel, despite limited evidence of substantial, Vietnam-sourced revenues, requires examining the political logic behind its engagement. North Korea’s Calculus Toward Vietnam Since 2024, North Korea has intensified efforts to revitalize exchange and cooperation with Vietnam amid deepening ties with Russia and increasingly strained relations with China. That year, the Workers’ Party and Foreign Ministry sent delegations to Hanoi; Vietnam reciprocated with visits to Pyongyang for talks on public security, defense, and political and cultural cooperation. These exchanges culminated in To Lam’s October 2025 visit to Pyongyang – his first as party leader and the first by a Vietnamese top leader in 18 years. Kim Jong Un’s elaborate reception of Lam marked the highest engagement point since his 2019 state visit to Hanoi. During Lam’s visit, the two sides signed agreements spanning foreign affairs, defense, culture, media, aviation, judicial assistance, investment, and health, including a double-taxation avoidance pact. The presence of both countries’ foreign and defense ministers signaled a structured effort to normalize engagement. While details of the defense accord remain opaque, analysts suggest Vietnam may seek technical insights from North Korea’s battlefield experience in Ukraine, while Pyongyang aims to expand its diplomatic reach within ASEAN. Pyongyang’s motivation for strengthening ties with Vietnam extends beyond preserving permissive conditions for illicit finance. It reflects a broader diplomatic calculus: to reframe North Korea as an active participant rather than an isolated outlier in the emerging multipolar order. During the 80th anniversary celebrations of the Workers’ Party of Korea, Kim Jong Un stood at the center of a carefully choreographed tableau flanked by senior Chinese, Vietnamese, and Russian officials. The symbolism was deliberate, evoking ideological kinship among Asia’s remaining socialist states while signaling Pyongyang’s ambition to establish itself as a key player within that shrinking fraternity. Kim reinforced this message in his anniversary address, declaring that “the international prestige of our Republic as a faithful member of the socialist forces and a bulwark for independence and justice is further increasing with each passing day.” His rhetoric sought to recast North Korea not as a pariah but as a principled defender of sovereignty resisting external coercion. Lam, positioned immediately to Kim’s left, embodied this narrative – his placement signaled Pyongyang’s intent to diversify its diplomatic imagery and demonstrate legitimacy beyond Beijing and Moscow. For Hanoi, the optics were equally strategic. Vietnam’s “bamboo diplomacy” – resilient in purpose yet flexible in execution – contrasts with Pyongyang’s confrontational “toughest anti-U.S. counteraction” posture. Yet both share a structural instinct: each views multipolarity as a buffer against dependency and a source of maneuvering space. Their engagement is less about ideological solidarity than strategic complementarity. In this light, the new cooperation agreements are less breakthrough than calibration. Pyongyang gains visibility and limited legitimacy within ASEAN’s diplomatic ecosystem, while Hanoi reinforces its image as an independent, bridge-building power able to engage all sides. Beneath the ceremony lies a quiet logic of mutual utility – each state leveraging the other’s diplomatic bandwidth to project flexibility and relevance in a crowded multipolar arena. Conclusion North Korea’s persistence amid tightening sanctions underscores the adaptive logic of its small-node strategy: generate repeatable cash flows by nesting within legitimate structures that provide enduring cover. While designed for autonomy, Vietnam’s diversified diplomacy and process-driven governance inadvertently furnish structural seams through which sanctioned actors operate. This dynamic does not imply complicity; it highlights the governance challenge of multipolarity, where institutional density and procedural gradualism can obscure enforcement gaps. In the post-PoE era, cash sustains Pyongyang’s survival, but cover sustains its reach. Thus, the North Korea–Vietnam link functions less as a revenue hub than a resilient node of legitimacy and access – a case study and a cautionary tale. The test for regional mechanisms is whether they can evolve faster than the networks that exploit them.