By Ling Xin

Copyright scmp

David Baltimore, the Nobel Prize-winning American biologist who died this month at 87, built a legacy in China through decades of scientific exchange that helped the country rise as a global powerhouse in life sciences.

Baltimore revolutionised gene research in his 30s and went on to mentor dozens of Chinese researchers and advise on the creation of top research institutions in the nation. His final paper was published in a Chinese journal.

Since his passing, scientists in China and Chinese-American researchers have remembered him for strengthening the country’s scientific foundation and fostering collaboration across borders.

Cheng Genhong, an immunologist and one of Baltimore’s former students who has worked in both the US and China, said in a tribute that Baltimore’s scientific vision and humanistic spirit had a profound impact on the global research community, especially in China.

“Dr Baltimore visited China many times, with his footprints across numerous universities and research institutes,” wrote Cheng, now head of the Suzhou Institute of Systems Medicine, which Baltimore helped establish. “He enjoyed face-to-face exchanges with students and faculty, gave thought-provoking talks, and tirelessly built bridges for collaboration.

“His contributions went far beyond the usual duties of an academic adviser, reflecting his genuine belief that science knows no borders and his deep desire to create pathways for young talent around the world – a legacy that commands lasting admiration.”

Shan-Lu Liu, a virologist at The Ohio State University and president of the American Society for Virology, called Baltimore “a towering figure in biomedical science” whose discoveries fundamentally changed our understanding of how retroviruses replicate and how cancer can arise from viral infection.

“Importantly, Dr Baltimore championed global scientific exchange, facilitating strong collaborations between the United States and China that enriched virology and biomedical research,” Liu said. “His vision, generosity and commitment to global scientific collaboration leave a profound and enduring legacy.”

Baltimore’s personal connection to China ran deep. His wife, molecular virologist Alice Huang, was born in Nanchang and moved to the US in 1949. The pair met at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in San Diego, married in 1968, and built parallel scientific careers while raising a daughter.

Over the decades, Baltimore devoted himself to training hundreds of young researchers, many of them from China. Some became leading figures in their fields, either continuing their work in the US or returning to China to launch new research programmes.

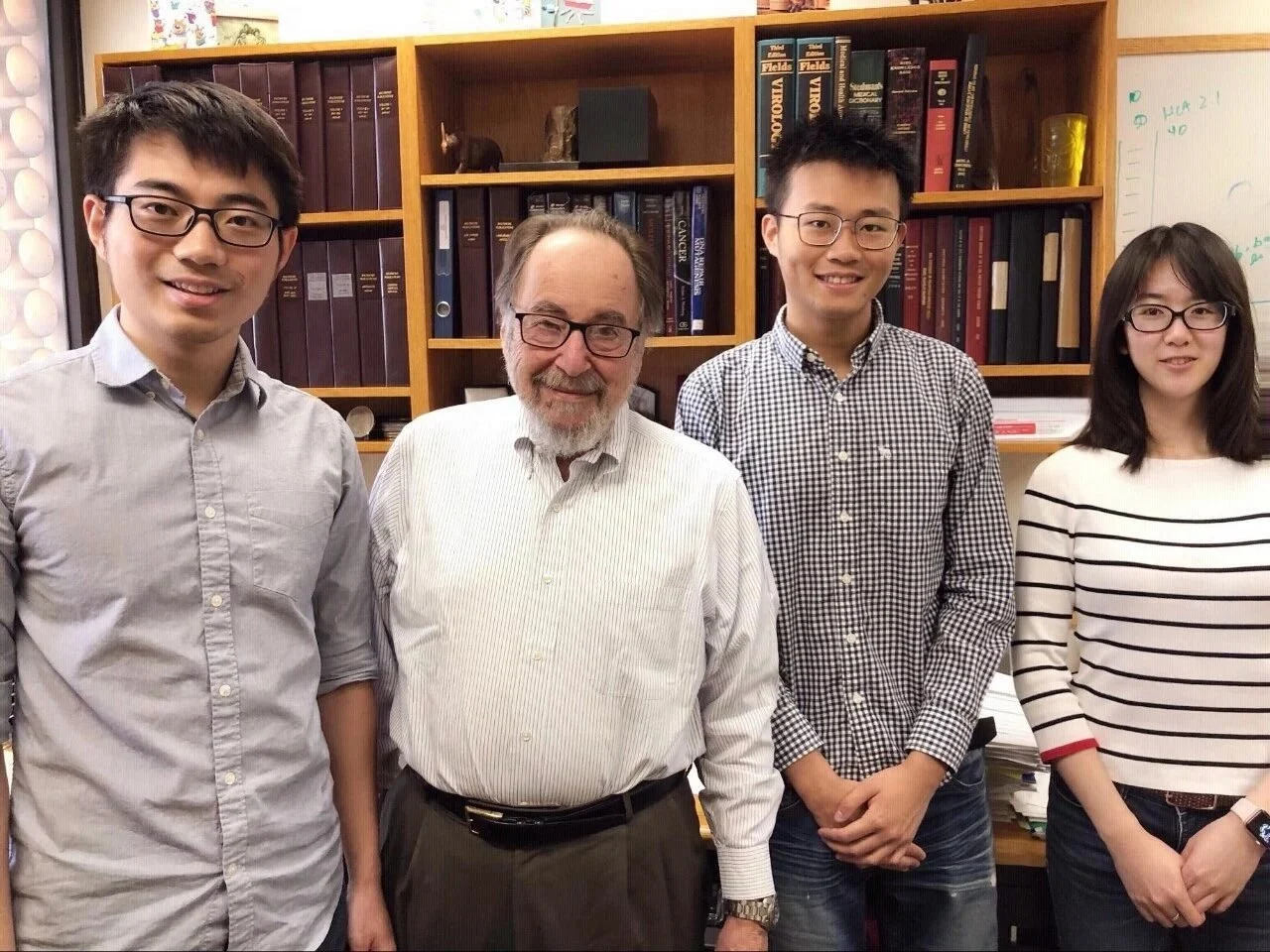

To name just a few, Cheng and Ren Ruibao were both trained under Baltimore as postdocs at Rockefeller University in the 1990s. Cheng later became a professor at the University of California, Los Angeles before returning to China. Ren held a tenured professorship at Brandeis University and is now director of the Shanghai Institute of Hematology.

Among Baltimore’s US-based protégés, female researchers Xin M. Luo and Lili Yang built influential careers in immunology after training in his lab at the California Institute of Technology in the 2000s.

Luo, now a professor at Virginia Tech, studies how the immune system interacts with gut microbes and contributes to autoimmune diseases. Yang, a professor at UCLA, leads a lab developing engineered immune cells to treat cancer and other disorders.

In his tribute, Cheng noted that Baltimore’s influence extended beyond individuals. “He recognised the huge potential of Chinese science early on, served as an adviser to multiple institutes, and promoted the creation of new research centres to meet the needs of a rapidly evolving scientific landscape,” he said.

Drawing on his leadership experience at MIT’s Whitehead Institute, Rockefeller University, and Caltech, Baltimore played a central role in founding the Suzhou Institute of Systems Medicine. He was co-chair of its international advisory board for a decade, helping shape its research agenda in cancer, infectious diseases and immunotherapy.

In 2018, shortly after Westlake University was approved for establishment, Baltimore was invited to join its governing board and advisory committee. Though he seldom served on university boards, he accepted the offer with enthusiasm, saying he was “intrigued by the vision of a small, research-driven institution emerging from China”, the university said in a post on its website.

“We deeply mourn Professor David Baltimore – a Nobel laureate, a brilliant scientist, an exceptional educator, and a beloved member of the Westlake family whose name is etched into our history. His legacy will live on,” it said.

Even towards the end of his life, Baltimore’s connection with China endured. On September 4, two days before his death, he co-authored his final paper with Cheng and another former postdoc in Immunity & Inflammation, a journal recently launched by the Chinese Society for Immunology.

The study examined how a protein, called RelB, helps control inflammation in the gut by keeping immune cells in check. The findings could shed light on diseases like inflammatory bowel disease – a fitting final chapter for Baltimore, who spent his career uncovering how the immune system responds to threats.

The paper also served as a passing of the torch, Cheng wrote. “The molecular pathways Dr Baltimore uncovered remain central to ongoing research, and the questions he raised will continue to guide discoveries that advance human health,” he said.

“His remarkable achievements and personal character will continue to inspire generations of students to reach new academic heights and overcome scientific challenges.”