Whither the men?

Not in your local bookstore, that’s for sure. For the past several years, writers and pundits have been wringing their hands over how few men are supposedly writing and reading fiction today. It is numerically true that women make up a majority of fiction readers and nearly always have. But this crisis is apparently of both new literary and social import. In December, still reeling from the reelection of Donald Trump, thanks in part to the support of young men, the creative-writing professor David J. Morris declared that “these young men need better stories — and they need to see themselves as belonging to the world of storytelling.” Once they do so, Morris implied, they will cease their rightward drift and become empathetic, liberal creatures once more.

He wildly overestimates the powers of literary fiction. Still, why don’t men read? For lack of the right books, it would seem.

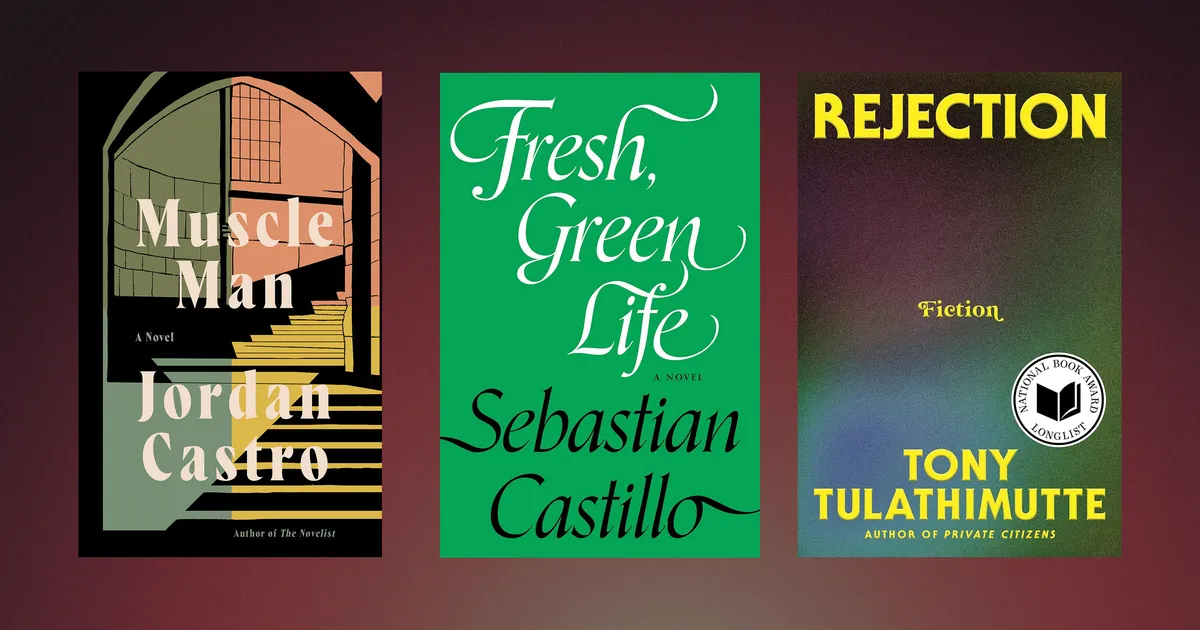

Men, we are assured, will return to reading when they see their own experiences reflected in contemporary fiction. A number of books over the past few years have attempted to capture a sliver of this audience. Call them novels of masculine tedium. These books, like Sean Thor Conroe’s Fuccboi; Adem Luz Rienspect’s Mixtape Hyperborea; Tony Tulathimutte’s Rejection; Sebastian Castillo’s Fresh, Green Life; and most recently, Jordan Castro’s Muscle Man, all depict the male psyche as a pulsing wound of self-conscious neurosis. Their men go online way too much, where they are bombarded by visions of contemporary masculinity: left-wing Twitter posturing, philosophy videos posted by lifting influencers, Wikipedia rabbit holes on all things crunchy and prehistoric. All this scrolling feeds a gnawing anxiety about the status of men today, imperiled by shifting cultural norms and technological addictions — an insecurity at the core of debates about the place of men in literature today. Desperate to cajole readers away from their phones, these writers deploy online language and screen-friendly forms. In the process, they have all written books that demonstrate what the novel might increasingly become in a world of ever-more-fragmented attention spans, where literacy rates are falling and screen time is skyrocketing and few people, not even self-consciously “literary” writers, are immune: a form continuous with the internet and increasingly inextricable from the demands of the digital world.

Let’s start with the most recent of them. Jordan Castro’s Muscle Man, out this month from Catapult, follows a man named Harold who teaches literature at Shepherd College, a liberal-arts institution in “the northern-most part of the south.” Having worked hard to rise from his working-class background, Harold now despises his job, the eerie building where he teaches, his liberal co-workers more concerned with “various abstractions” like inequality than literature, the administration that prioritizes student feelings over the work of education. Most of all, Harold hates being alone with himself. Harold believes himself an Übermensch, he calls himself “the One” constrained by “the All” of his buglike colleagues and “zombified” students. Yet whenever given the chance to express himself, he stutters, turns away, disappears into his phone. Harold even wrote a dissertation and then a novel on exceptional men punished by a mediocre society — beliefs deployed earnestly, yet interpreted by his (minimal) public as satire.

Castro understands better than most that not only contemporary life but contemporary consciousness have become hopelessly contaminated by the internet. His novels center around characters scrolling helplessly, until the images on their screens, and the voices in their ears, become intertwined with their sense of self. His 2022 debut, The Novelist, devotes slightly fewer than 200 pages to slightly more than two hours of a Friday morning, in which an unnamed narrator steeps tea, scrolls Twitter, washes the dishes, goes to the bathroom, fiddles with his Google doc, and clicks back to Twitter again — anything to avoid working on an autobiographical novel about his own drug addiction. In Castro’s signature move, he creates a kind of digital-consciousness stream, stacking a series of connected but unrelated thoughts, sensations, and impressions on top of one another, evoking the cacophonous simultaneity of contemporary life. “David—backpack—laughing—food,” runs Harold’s inner monologue during a faculty meeting, struggling to piece together his fragmented attention.

The sole bright spot in Harold’s life is Casey, an award-winning writer and tenured professor who introduced Harold to weightlifting. “Casey seemed set apart,” Harold reflects. “He was not zombified and sterile like the rest of the faculty.” Contemptuous of academia, which he considers feminine and intellectually stultifying, Casey guides Harold toward the gym, where he will build up a strong, vital body to counteract the “dead matter” of his colleagues, and the weak, parasitic ideas they mindlessly propagate. Harold only feels truly himself while at the gym, and throughout the day he does miniature bicep curls during meetings to make mundane interactions and perceived slights seem bearable. Yet this strength leads only to further insecurity. He spends the novel’s first part desperate to leave campus and lift weights, and terrified that by forgetting to pack a lunch, he has forced his body to feed on his precious muscles.

When lifting, Harold becomes a philosophical being, expressing through the flow of blood what words cannot convey. Yet when forced to actually communicate with, say, any of the attractive women at the gym, he breaks down completely, crushed by self-consciousness over how his actions and words will be interpreted by them — and in the process acting much creepier than if he had just said hello. The deeper his thoughts, the less he is able to convey, a gap which he blames on the parasitic, feminizing power of words, while the real problem festers elsewhere within his insecure and malleable self.

Castro is a precise and immensely readable stylist. He’s fun to read, and very funny, and his novels do not read like a simple transposition of online life to the page. Muscle Man is a deeply ironic book, creating a vast chasm between Harold’s strongman self-image and his infantile powers of self-expression. When he rants at length about vitality, weakness, and the corrupting power of liberal academia, it’s impossible to take him seriously. We are told that politics is for cowards, literary analysis is for women, education is a system of liberal indoctrination, brave individuals must resist the herd. He might mock his colleagues for their various social-justice crusades, but they at least seem to move through the world, while Harold is trapped in the prison of his own body.

Harold might believe himself an Übermensch who doesn’t need public affirmation. Yet in order to organize his own thoughts, he must imagine that he is delivering them as a speech to his colleagues or on a podcast. That this is only possible within his private monologue — that he flubs every single moment of public expression — is the novel’s constitutive joke. Without an audience, he is no one.

Yet Castro, too, is obsessed with capturing his audience and controlling their attention, an obsession which gets in the way of his own fiction. Late in the novel, the professor’s latent paranoia coalesces into a meeting with a pair of colleagues and two administrators — one of whom, he notices, distressed, seems also to lift. The administrators want to know Harold’s thoughts about Casey, who, they say, “has been teaching certain texts, saying things during lectures that have been causing harm in our community.” By keeping the accusations couched in vague, heterodox dog-whistling, he prevents you from coming to their own conclusions about Casey, and Harold, and the investigation as a whole. He imposes his view without giving you the breathing room to gauge if it might even be true, shrinking his novel to the size of his own mind, rather than opening it out to the reader, and the world.

This kind of self-consciousness has become more common in literature today. It can feel like the expression of an anxiety about not being read, period, in a world where most Americans, male or female, are not reading novels at all. Across genres and styles, new books must maintain a death grip on the reader’s attention, fearful of losing it to the many readily accessible distractions lying at most one foot from the book itself. To manage this, they prioritize textual legibility and narrative immediacy, qualities which even the self-confident Castro shares with many of his peers. Fuccboi’s Conroe has asserted that he writes for people who don’t read, and the first “commandment” of his recent Blast2 manifesto declares: “U MUST BE READABLE & COMPREHENSIBLE…”

In our era of infinite disposable distractions, then, writers must apparently meet the people where they are, in their own denuded language. Not that everyone agrees. Sebastian Castillo ruthlessly mocks this kind of aestheticized internet speech in June’s Fresh, Green Life, puncturing his narrator’s self-importantly formal inner monologue with dispatches from real (online) life: a teenage boy boasting that he’s going to be “getting that podcast pussy tonight”; an inexplicably popular tweet that says only “shitting piss/cummm out of my dickkk.” Yet as I noted elsewhere, his virtuoso performance of internet-addled intellection ultimately hedges its bets. After an entire novel spent shit-talking and being shit-talked, the narrator confronts a young man reading Jordan Peterson on the subway, denouncing this stranger for his naïveté, his cowardice, his fear of living with others — qualities, we’ve well been made to understand, apply as much if not more to Castillo’s callow narrator himself. The author is telling us how to feel about his character, his novel, his project in general; he is telling us what it all means, exactly, with no room for misunderstanding. Like Castro, he seems intent on leaving no ambiguity, no contradictory gap in which the reader might come to their own perspective on the narrator and his illusions.

Adem Luz Rienspects, too, who self-published Mixtape Hyperborea in 2023, seems obsessed with confusing or otherwise challenging his reader. In July, Rolling Stone profiled Rienspects along with other members of the L.A. alt-lit scene, declaring them the best chance of making “literature cool again among young men.” Like Muscle Man, Mixtape follows a self-important, inarticulate mediocrity on the fringe of a minor American metropolis. Unlike Muscle Man, Mixtape reads like a politically incorrect CW pilot — Kids by way of Perks of Being a Wallflower. Spanning the 2007–2008 school year, it centers on a Camry-driving senior at a private Christian preparatory academy outside of a city in the American Southwest. He lifts weights, hits on girls, smokes weed, and drives around listening to curated mix CDs, which he calls mixtapes. He hangs with his friends, distinguishable only by their names. At the end, he loses his virginity, and he and his buddies watch as a cloud of fire-extinguisher fog is blown away by the wind.

The book is padded full of the thin, present-tense prose beloved of young writers, who mistake its vagueness for urgency. The narrator eavesdrops “with sonic precision” and feels “a kind of rising adrenaline” during tense situations. When a group of people come together, “there’s an undeniable feeling of community.” Most paragraphs are one sentence long, to keep your eye scrolling steadily down the page.

Rienspects writes under a pseudonym (he makes us “re-inspect” the world around us — get it?) , apparently to keep the real man from getting canceled. The kids act like not particularly imaginative teenagers, peppering their conversations with the occasional jab at “retards” or “mexies”; when one boy orders a salad as a main course, the narrator declares it “(very Asian behavior).” The edgiest joke is on the back of the book, where you’ll find three defensively satirical pans from fictional critics with Jewish names. Rienspects has set his novel in 2007, when he would have been around 8 years old. Unsurprisingly, he flubs basic facts and essential truths. His characters don’t use cell phones, unthinkable for teenagers at a wealthy prep academy in the mid-2000s. They listen to CDs, they don’t have iPods, and they almost never go online. In trying to resurrect his vaguely recalled pre-internet utopia, then, Rienspects reveals that he cannot even imagine a time before web2.

But his nostalgia for pre-internet life is revealing. These years seem to represent a kind of utopia for him, when file-sharing allowed music and information to flow around the world, yet before social media (and digital surveillance) became omnipresent. In the Rolling Stone profile, he yearns for “a new consciousness that emerges that’s post-political, anti-tech, anti-stimulation.” He writes, like all these authors write, in a way that feels inescapably post-internet, and that strikes me as essentially coming from a place of fear: a fear that you will misunderstand, get frustrated, get bored, get outraged; that you will put the book down and go back to your phone.

Only Tony Tulathimutte does not write from this place of fear. The many self-loathing characters of his 2024 short-story collection Rejection self-medicate with hardcore pornography, with bizdev self-help mantras, with the pity they ritually manipulate out of family and friends. Take the Feminist, a man with small shoulders and “lenticular baldness” who stars in a story of the same name. The Feminist is a man who from an early age gained plenty of female friendships but never a romantic relationship, not even a kiss. From his teens to his 20s and on into his 30s, our protagonist consoles his deep and unshakable sense that heartbreak is romantic and dignified, whereas rejection “only makes you a loser.”

The Feminist is precisely one of those liberals mocked all throughout Muscle Man, an ostensibly progressive male ally who filters every relationship and desire through the “various abstractions” of ideology. But Tulathimutte does not want to be glib, like Castro; he actually wants to understand how such concepts mold and mutate the psyche. The Feminist lives among women and adopts a rhetoric of feminine liberation. He does not catcall, does not make unwanted passes; he always asks before coming in for a kiss, an enlightened chivalry which he believes, deep into adulthood, to be work enough to earn him a date. When it does not he begins paying for sex, and though he insists that he respects the sex workers, he finds the experiences unfulfilling, even degrading. He watches domination porn, though only the kind made under good conditions, and with respect for the actors. His penis grows so ragged he has to stimulate himself with the rough surface of a “textured plumber’s glove.” He retreats into an online community of other men with small shoulders and open minds, men who have read the feminist texts, who by their own reckoning have made every attempt to understand the plight, the lives, the desires of women — women who, they now insist, have never made to understand them. “When I die,” the Feminist writes, “my entire being will evaporate without residue, with no one left to know what I’ve had to endure absolutely by myself.”

In “The Feminist,” we have everything our defenders of masculine literature desire: deeply sexual beings who cruise the internet, giving vent to the unspeakable frustrations of men today. But Rejection does not hide behind the ironic, the provocative, the self-consciously confrontational. As “The Feminist” drives toward its namesake’s terroristic auto-da-fe, Tulathimutte does not come up for air. He buries you inside of his narrators, his stories, the ugliness of this contemporary world in which we are all trapped, and then you suffocate.

The effect is awful, claustrophobic, immensely dispiriting; it is also fundamentally literary. While Tulathimutte directly embeds text messages, forum posts, and extracts from dating profiles into his stories, the effect has more in common with the 19th-century epistolary novel than modern internet fiction, deepening the communication between characters, and thus between book and reader, rather than flattening everything into a seamless feed. Rejection might be a book about people too much on their phones, but it does not by any stretch read like being on your phone. It reads, horribly, like the world. Thank God for that.