By The Eagle Online

Copyright theeagleonline

When Temitope Afolabi realised her husband could get imprisoned due to a N48 million debt he incurred from a bad business deal, she resolved to become a surrogate to earn money to save him. She had initially considered selling one of her kidneys, but unable to find a source, she settled for being a surrogate.

Surrogacy is a form of assisted reproduction in which a woman (the surrogate) carries a pregnancy on behalf of a third party—the intended parent. Usually, the surrogate is paid for her service in a commercial arrangement.

The global surrogacy industry is valued at $27.9 billion, and the United Nations regards the practice as a form of violence against women and girls.

Meanwhile, in Nigeria, surrogacy is becoming increasingly common. Celebrities like Nancy Umeh, Ini Edo, and Chimamanda Adichie have used surrogate services. Lifestyle influencer Ife Agoro also plans to use one regardless of health challenges.

But what is the experience of surrogates in Africa’s most populous country, and how did it become so common? I followed Temitope’s journey from pregnancy to postpartum through a Facebook Messenger conversation, where she unveiled her experience with me. I would eventually meet with her for more details.

Temitope became a surrogate in May 2024. She was paid about N2,233,000, including transportation, accommodation allowance, childbirth fee, and wardrobe allowance.

However, her compensation did not reflect Nigeria’s economic realities. Her N3,000 transportation allowance was insufficient to cover her logistics. She lives at Sango Ota, along Oju Ore in Ogun State, and was to travel 41.9 kilometres to her healthcare centre in Ikorodu.

Although her transport fare was later increased to N5,000 after several complaints, the catch was that she would visit a clinic in Ikeja, Lagos State. Amidst tears, Temitope swore she always added an extra N1,000 from her funds to cover the lapse in logistics costs while enduring the stress of commuting farther. She also barely had enough money to eat after she paid her rent and her children’s school fees.

Her teary voice, while sharing her experience, soon switched to anger when she recounted that her agent collected N450,000 for logistics from intending parents, alleging they went to the hospital via Uber.

“Nigerians are users,” she said, her voice hoarse. “They just use people because of what they are going through. They did not even look at the stress of carrying pregnancies, vomiting, and everything. They are just using us as slaves because they believe that if you don’t do it, another person will.”

Although Temitope was informed of the compensation plan from the outset, she wasn’t aware of the terms and conditions until much later. Her contract, dated August 26, 2024, was given to her to sign when she was already three months pregnant. It includes a death clause stating she understands that she could die.

A BBC report highlights that Nigeria is the worst country to give birth in, with one death happening every seven minutes. Also, Temitope’s contract mandates that only the intended parent and the doctor can decide how to proceed if the pregnancy is harming her health. She is also forbidden to speak to the media.

During her journey as a surrogate, Temitope was prohibited from leaving her home and eating specific food items for two weeks: noodles, orange, pineapple, mineral drinks, and anything that burns were forbidden. She was also mandated to visit the agency regularly, even when she didn’t feel like it, or her child was sick.

After she delivered the baby on February 24, 2025, Temitope suffered several medical conditions. She began menstruating thrice a month, had a fibroid and ovarian cysts, and often suffered from lightheadedness. When she complained, she was told by her agent that post-partum healthcare ends at six weeks.

“I feel used, stupid, and depressed,” she said, expressing regret at being a surrogate. “At the end of the day, my husband still went to prison on December 18, 2024.”

Like Temitope, another surrogate I spoke to reported medical challenges after childbirth. The student of the University of Benin, who wants to be kept anonymous, gave birth to twins as a surrogate. She shared that her healing process after birth was difficult, and she spent half of the money she was paid just to get better.

Dr Sunday Olarenwaju, the managing director of Mother and Child Hospital, said that twin pregnancies are dangerous.

He explained that the more children a woman carries, the higher the risk of being exposed to diseases, including hypertension, haemorrhage, and even death. Researchers also document that when a woman gestates an embryo unrelated to her genes, she is more likely to develop placental issues and preeclampsia, among other ailments.

“Nigerians do not understand,” Temitope said, explaining she once tried to raise concerns about the experience of surrogates on social media. “They say we agreed to it. If not for financial problems, who would agree to such a thing? There is no one to fight for us,” her voice flattened in resignation.

Meta’s complicity in fuelling surrogacy in Nigeria

While the surrogates I conversed with are of different age groups, one thing they have in common is that they belong to the Facebook Surrogate group: Egg donor and surrogate mother in Nigeria. The community, created on January 5, 2023, has over 4,800 members within two years.

Countless surrogacy adverts flood the group daily. Some adverts encourage people to contact them via DM (Facebook Messenger) and WhatsApp.

Meta is the parent company of Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, and Messenger. The multinational technology company has an estimated monthly active user base of 3.98 billion on its apps and has a community standard guiding its platforms.

Its website states that it has “a responsibility to promote the best of what people can do together by keeping people safe and preventing harm.” Its Community Standards, which guide Facebook advertisements, also prohibit content that facilitates human exploitation, such as sales of children and labour exploitation.

I contacted Meta through their dedicated email for the press. I inquired whether they consider surrogacy a form of human exploitation and, if so, why surrogacy groups such as Egg donors and surrogate mothers in Nigeria, which facilitate surrogacy for women like Temitope, exist. The tech giant deleted the group, with the response,

“Ads and Groups that exploit people through the sale or illegal adoption of children violate our policies, and we remove this content when it’s found – as we have done in this case.”

However, Olivia Maurel, the spokesperson for the Casablanca Declaration, an international non-governmental organisation working on a universal ban on surrogacy, advised that, beyond deleting such groups, Facebook should implement a policy that monitors and bans all forms of surrogacy advertisements in vulnerable regions like Nigeria.

Misinformation abounds

Beyond its rules against human exploitation, Meta is explicit in its intolerance for misinformation. Yet, conversations with surrogate agents on WhatsApp are often half-truths, outright lies, or concealment in their pursuit to recruit women.

One such experience is an interaction I had with a surrogate agent, Omobolanle Oguntolu, on WhatsApp. I found her advertisement for Surrogacy on Facebook in the Surrogate Mothers Nigeria group, which has over 5,600 members. She added her phone number to the post so interested surrogates could contact her through her agency, Regal Surrogate Services.

I brought the group Surrogate Mothers Nigeria to Meta’s attention, and they deleted it. However, when I contacted Omobolanle on WhatsApp about being a surrogate, she claimed she had helped more than 35 women become surrogates.

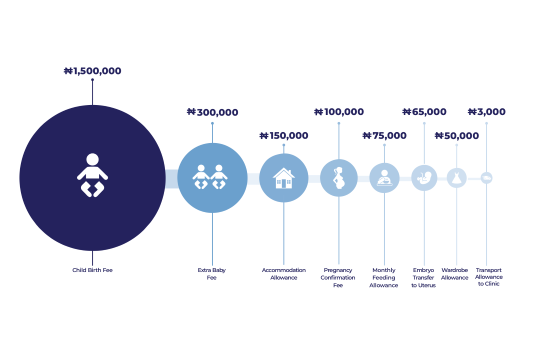

She told me I would be paid about N2,243,000 and sent me a breakdown.

I tried negotiating a higher figure with her and other agents, but soon discovered it was a take-it-or-leave-it deal. One surrogate agent, who identified herself simply as Sophia, had a disclaimer to the financial offer she gave me. “Kindly read through the rules and regulations of the payment plan; there must be no complaints once you have signed the contract.”

I returned to Omobolanle. I told her that it was my first time being a surrogate and that she should tell me everything I needed to know. She responded that aside from the payment, there wasn’t much, but she offered to answer any more questions I had.

“Since this is your first time, you should know what you are getting yourself into,” she said.

But when I asked her which hospital I would use as a surrogate, she told me it was confidential and she wouldn’t give me the details until I was on my way there. Puzzled, I asked her how I could research the hospital with which my fate lies; she said I couldn’t. I asked what would happen if I experienced complications during the pregnancy or if I died. Surprisingly, she gave me a “100% guarantee for safety.”

Jumoke Falade, a nurse practitioner at Lagos State University Teaching Hospital, was shocked that surrogacy could be tagged “safe,” saying that it came with risks associated with pregnancy, including death.

Omobolanle also claimed that as a surrogate, I would birth the baby through a cesarean section (CS) because it was “better and safer” than a natural birth. However, Olanrewaju, who is also a gynaecologist at Mother and Child Hospital, revealed that natural birth, not CS, is better for a surrogate because it comes with a faster post-delivery recovery process and does not leave a scar.

The medical professional further clarified that surrogacy does not deal only with the usage of the woman’s womb.

“The woman’s lungs are being used to help the baby breathe. The blood is used for circulation, and the nutrients from the woman’s body nourish the baby,” he said. “The womb is only the house of the baby.”

Beyond the health misinformation, Omobolanle affirms that commercial surrogacy is legal in Nigeria, and that is why it is a norm in the country.

But, legal practitioner Marvellous Igbineweka argues that the National Health Act of 2014 provides a framework that makes commercial surrogacy illegal. The Act prohibits the donation of human organs, cells, or tissue for monetary purposes, gains, or profit. The learned fellow further cited that the Child Rights Act of 2003, Section 13 of the Trafficking in Persons (Prohibition) Enforcement and Administration Act, and Order 23 of the Code of Medical Ethics in Nigeria can be used to argue the illegality of the practice.

Another lawyer, Dogo Joy Njeb, emphasised that it is only an argument. She states that “anything the law has not explicitly criminalised is legal.” She added that Nigeria allows citizens to engage in contractual agreements, under which many surrogate arrangements occur.

So, when I asked Omobolanle why I couldn’t find online information about her agency, Regal Surrogate Services, to confirm her legitimacy, she responded that it is just something “she calls herself.”

Nigeria government complicity

Omobolanle’s surrogate agency is unregistered, but no Nigerian law requires her to be. Nigeria is silent on the practice of surrogacy, so the legality of commercial surrogacy is debatable. Members of the National Assembly, responsible for making legislation in the country, have attempted to pass a law but were unsuccessful. The Bill for Establishing a Nigerian Assisted Reproduction Authority (2012) and the Assisted Reproductive Technology (Regulatory) Bill 2016 were not passed due to lawmakers’ lack of majority support.

I contacted Christiana Eguma, the Head of the Gender Technical Unit (GTU) in the National Assembly, regarding Nigeria’s lack of a surrogacy bill. Christiana is also the Programme Coordinator of Women’s Rights Advancement & Protection Alternatives (WRAPA). She stated that the GTU would intervene by developing a policy brief to highlight the gender, ethical, and health implications of unregulated surrogacy practices.

However, Hon. Olamijuwonlo Alao-Akala, a House of Representatives member representing Ogbomoso North, South and Oriire constituencies, is sponsoring a National Surrogacy Regulatory Commission Bill (2024) to remedy the lack of legislation in the country. The bill passed the second reading in the House of Representatives in October 2024. It is expected to monitor and mandate the registration of surrogate agencies, making surrogacy legal. It will also prohibit monetary compensation in surrogacy arrangements (commercial surrogacy). This means that surrogates would not be paid for their service. Hence, carrying a baby without payment (altruistic surrogacy) would be the norm.

Regarding the bill’s relevance, Hon. Olamijuwonlo argued, “It is to regulate and evaluate surrogacy in Nigeria, thereby ensuring medical and health laws are not flouted.”

Similarly, Hon. Uchenna Okonkwo, representing the Idemili North/Idemili South Federal Constituency of Anambra State, is sponsoring a surrogacy bill titled “A Bill for an Act to Protect the Health and Well-being of Women, Particularly in Relation to Surrogacy and for Related Matters.” The bill will also criminalise commercial surrogacy but legitimise altruistic surrogacy.

However, Olivia, who is also a woman born through surrogacy, during an email correspondence with me, decries the problem with such bills.

“We should not differentiate between commercial and altruistic surrogacy, ever, because there is no real difference between the two. Both rely on the same mechanism: using a woman’s body to fulfil the desires of others, often at the cost of her own health, autonomy, and dignity.”

The United Nations also recommends that countries must eradicate surrogacy in all its forms, criminalise surrogacy agencies and those facilitating it. It states that lawmakers must nullify surrogacy contracts, provide exit support strategies for surrogate mothers and regard them as the legal mothers of the babies they carry.

I contacted Hon. Olamijuwonlo via X (formerly Twitter), WhatsApp and email regarding the bill he is sponsoring and the international standard, but he failed to comment. I then spoke to Hon. Uchenna Okonkwo about discussing his surrogacy bill. The lawmaker asked to call back in two hours but never responded to subsequent calls, texts, or emails.

Meanwhile, Olivia warns, “If Nigeria doesn’t act now, it risks becoming a hub for a global market that treats women’s bodies as tools and children as products.”

Back to Square 1

As Temitope continues to battle health challenges as a result of being a surrogate, the N1.3m she was paid for birthing the child was exhausted in three months.

She spent the larger portion of the money to feed, pay her four children’s school fees, send money to her husband in prison, and settle the debts she owed.

With all the money gone, Temitope now sells dried ponmo (local cow skin), hoping she can make enough to survive and care for her children.

Simbiat Bakare