Copyright scmp

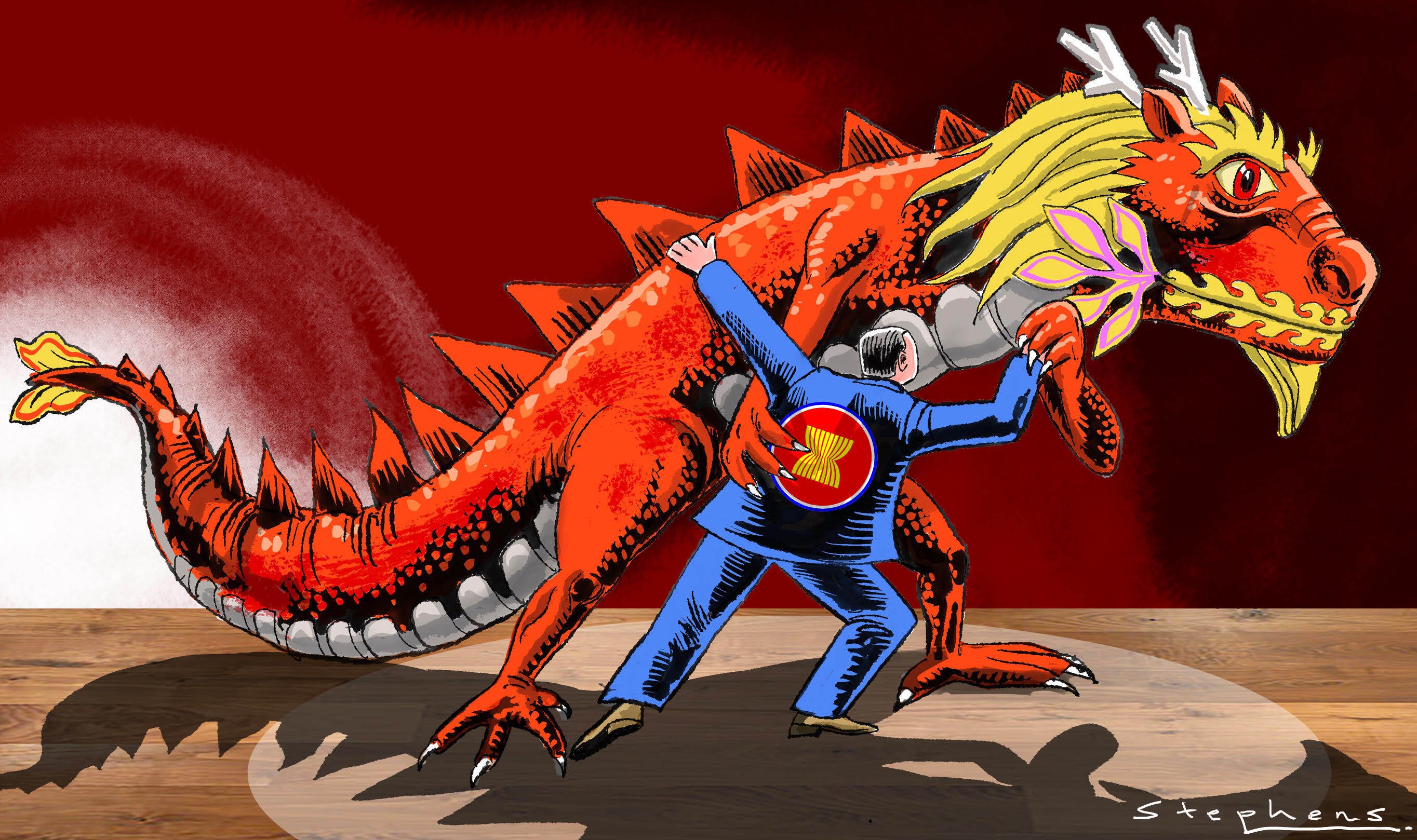

At last month’s Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) summit, China and the bloc upgraded their free trade pact in the areas of environmental protection, product quality and support for small businesses. Premier Li Qiang contextualised the agreement in light of “greater development challenges” facing Asean nations, as they are “unfairly subjected to steep tariffs”, an indirect criticism of the erratic measures unleashed across the region by US President Donald Trump. Another noteworthy moment at the summit was the formal accession of East Timor, a prominent economic and trade partner of China, Indonesia and Singapore. On the surface, Sino-Asean relations have never looked more promising. Asean has been China’s primary trading partner since 2020, with bilateral trade surging from US$160 billion in 2006 to almost US$1 trillion in 2024. Chinese investments in infrastructure – from railways to ports and gas pipelines to energy grids – have played an instrumental role across both the continental Asean states of Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos as well as maritime nations such as Indonesia and Malaysia. On the streets of Thailand, one could easily find a BYD model. The Chinese electric vehicle (EV) company opened its first factory outside China in the Southeast Asian country. The SAIC Motor-CP partnership also speaks to the depth and pace of supply chain integration between the two economies. However, the reality is more complex. When I speak to policymakers, business elites and young students in Asean countries, the rise of China comes across as a double-edged sword. In their eyes, China is at once an exceptional source of indispensable exports and a daunting juggernaut that threatens to outcompete vast swathes of domestic producers. China’s astounding development in the past 40 years serves as both an aspirational exemplar and a demonstration of formidable strength, especially for countries with which it shares historically rooted territorial disputes. The State of Southeast Asia Survey 2025 conducted by the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute found that 52.3 per cent of respondents would align with the US over China when forced to choose between the two – a curiously phrased hypothetical – even though six out of the then 10 Asean members ranked the country as the most strategically relevant dialogue partner to the region. In the Philippines, a poll by OCTA Research in August revealed that 85 per cent of respondents distrusted China, with two-thirds attributing their sentiments to ongoing maritime tensions. Broader concerns loom over the ferocious competition posed by Chinese sophisticated and affordable EVs, lithium batteries, solar panels and a raft of advanced manufacturing goods. The “involution” of Chinese industries has spillover repercussions for its southern neighbours, with local producers feeling increasingly unable to compete effectively. Then, there is the real issue of xenophobia towards Chinese immigrants and fears of destabilisation by criminals originating from China. This is a cauldron of simmering discontent, which could boil over into a violent flare-up. One might suggest that Southeast Asian leaders and policymakers develop a more multidimensional understanding of the Chinese political system and increase communication with different economic stakeholders. For example, China’s commitment to “building a modernised industrial system” in the coming 15th five-year plan is partly fuelled by Beijing’s desire to withstand US-led efforts to excise the country from global supply chains. This is a goal that savvy Asean operators can leverage for their own gain. Of course, it takes two to tango. Politically, Beijing must learn to view itself through the lenses of emerging powers and the people who live there. It must recognise that its projection of technological advancement and economic prowess both impresses and intimidates. More affirmative policies and messaging centred around China’s constructive role in addressing shared worries in the region – climate change, unequal development, trade barriers for Asean exports and education disparities – would go a long way. With regard to territorial disputes in the South China Sea, Beijing should strike the right balance between deterrence-oriented assertion of its interests and the mitigation of mass resentment that plays into the hands of local politicians whose political legitimacy is propelled by repudiating China. A sincere acknowledgement of the centrality and importance of Asean institutions and an embrace of multilateral frameworks for dialogue are key. Commercially speaking, Chinese companies must work harder to embed themselves locally, through hiring local executives and managers, proactively serving the wider community beyond the diaspora on the ground and developing regional geopolitical expertise. In these areas, there is still room for improvement. In this regard, the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council and the Ministry of Commerce have a crucial steering role to play. They can expedite the comprehensive corporate localisation of China’s state-owned and private companies in Southeast Asia. Finally, in the same way that it benefited immensely from its access to Western markets through the 1980s and 1990s in the early days of the reform and opening-up, China must remember that market access is a pivotal source of goodwill. I was at the “Summer Davos” forum this year when Premier Li vowed that the country would become a “mega-sized” consumption power, doubling down on household demand in the coming years to spur economic growth. In positioning the country not just as an export engine, but as a proactive importer, he is arguably addressing the concerns of critics who worry about the significant trade dependence their countries experience in relation to China. We should hope that such rhetoric translates into substantive action.