Since the end of World War II, Brazil has attempted to establish itself as a prominent power player on the international stage. Recently, it has tried to be a leader on environmental and human rights issues. Now, as Brazil gears up to host COP 30 in Belém, a roguish side of the country’s national culture, Jeitinho Brasileiro, or circumventing rules to accomplish one’s goals, might diminish its global importance via insatiable greed from local hotels.

This Brazilian trait, in its positive form, can be used with creativity and flexibility to improvise solutions to bypass rules, allowing the poor to survive in a socially unequal country. However, Belém’s hotels are showing this culture in its most nefarious form by taking advantage of visitors wishing to attend COP 30. The stereotypical “Brazilian way” is on full display through elevated hotel accommodation rates amid shortages, jeopardizing the legitimacy of the climate summit, turning away poorer countries from attendance, thus raising red flags at the U.N. climate bureau; Brazil’s intended international green policy is starting to look anything but green.

In Belém, accommodations for COP 30 can cost up to $600 per night, far above the average cost each night in previous COP host cities. Still, the problem is not just with the hotel industry’s greed vying to make a score of a lifetime. The Brazilian government wanted to have a symbolic event close to the world-famous Amazon rainforest—where politicians will likely meet with Indigenous communities wearing suits, while taking photos wearing war paint. In contrast, the Indigenous communities, affected the most by matters discussed at COP summits, rarely are given the opportunity to take part in discussions that are pertinent to them.

While the images and debates at COP 30 will disseminate around the world and have a symbolic impact in the media, the coastal city of Belém, with its 1.3 million inhabitants, is not prepared to host such an event, as it is racing to expand its 18,000 hotel beds to receive an expected 45,000 attendees. In August, the city’s administration claimed to have 53,000 beds available while resorting to ships, Airbnbs, and rented homes as accommodation. The Brazilian government should have chosen Rio de Janeiro, with its 100,000 hotel beds, or São Paulo, which has 75,600 hotel beds. Still, Brazil’s heavily urbanized centers, São Paulo more than Rio, wouldn’t make for good photo ops or convey the notion that the world “cares” about climate change as being in heart of the Amazon would.

There are plans from the government to charge up to 100 percent of the hotels’ profits to contain abusive practices; meanwhile, the U.N. is putting pressure on Brazil to ensure rooms for $100 a day for delegates from the poorest countries and up to $500 for other nations. If no real actions are taken, COP 30 will further champion elitism.

For the record, Brazil already faces environmental and human rights challenges; the status quo has improved since the Jair Bolsonaro era, and although it may feel that the boot on the neck has been eased, it is not entirely free. Nevertheless, to compare the current administration with Bolsonaro, who isn’t keen on environmental and social causes, means that the bar is held almost at the bottom.

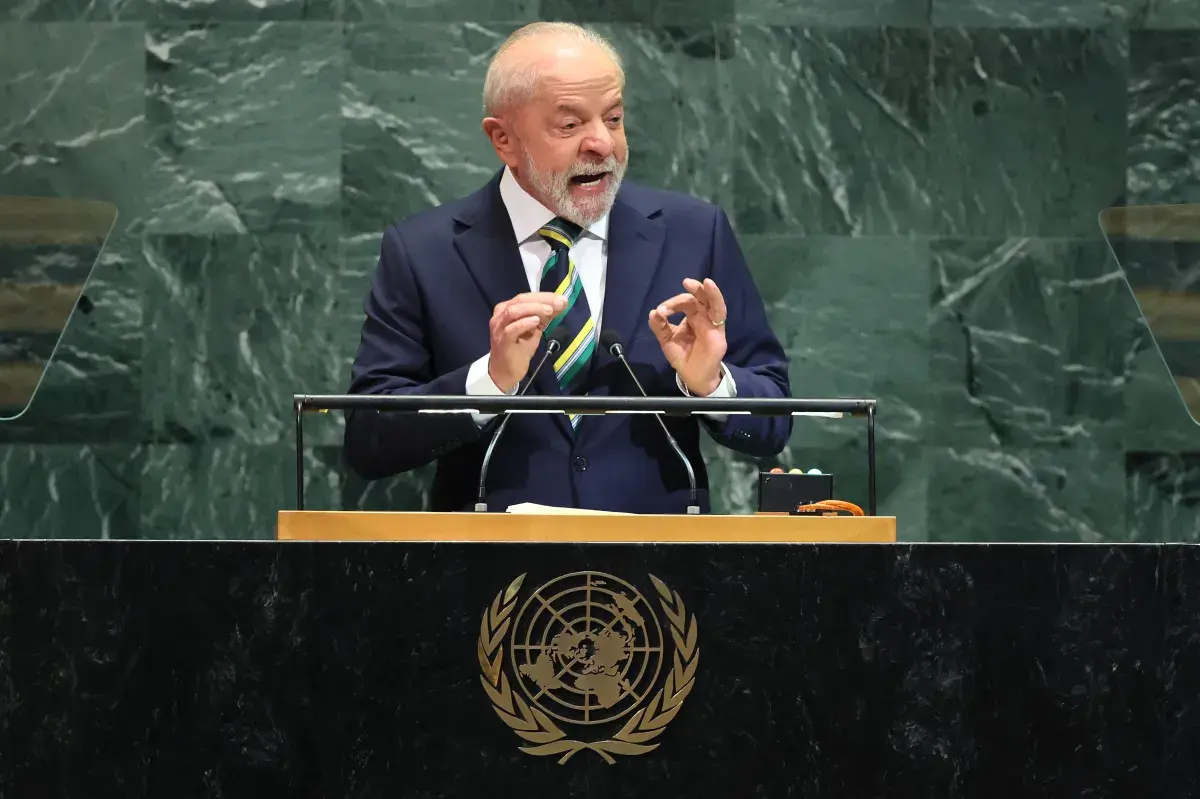

Brazil isn’t a green utopia. There is still the ongoing Yanomami humanitarian crisis, supported by the tentacles of growing Brazilian organized crime that wait on the margins to exploit Indigenous territory; the wildfires that plague the country’s biomes have hit record levels in 2024 and are still burning land and destroying lives, not to forget the 38 million wild animals trafficked yearly in a $23 billion industry. President Luís Inácio “Lula” da Silva and the Brazilian Congress also have a burning desire for oil reserves located in the Amazon. These are just some of the issues yet to be addressed by Lula and will likely not be addressed by future administrations.

Brazil under Lula might have good will toward improving environmental and human rights issues, but heightened hotel room accommodation rates remain in Belém, and Brazil’s international image as a “tropical paradise” won’t save it from the potential PR damage COP 30 may create—ultimately extinguishing its ambition to be a respected international power player.

Gabriel Leão works as a journalist and is based in São Paulo, Brazil. He has written for outlets in Brazil, the U.K., Canada, Mexico, and the U.S. such as WIRED, Al Jazeera, Dazed, Vice, Dicebreaker, Scarleteen, Women’s Media Center, Clash, Anime Herald, Anime Feminist, and Brazil’s ESPN Magazine. Leão also holds a master’s degree in communications and a post-grad degree in foreign relations.

The views expressed in this article are the writer’s own.