By Alex Williams,Jennifer Riggins

Copyright thenewstack

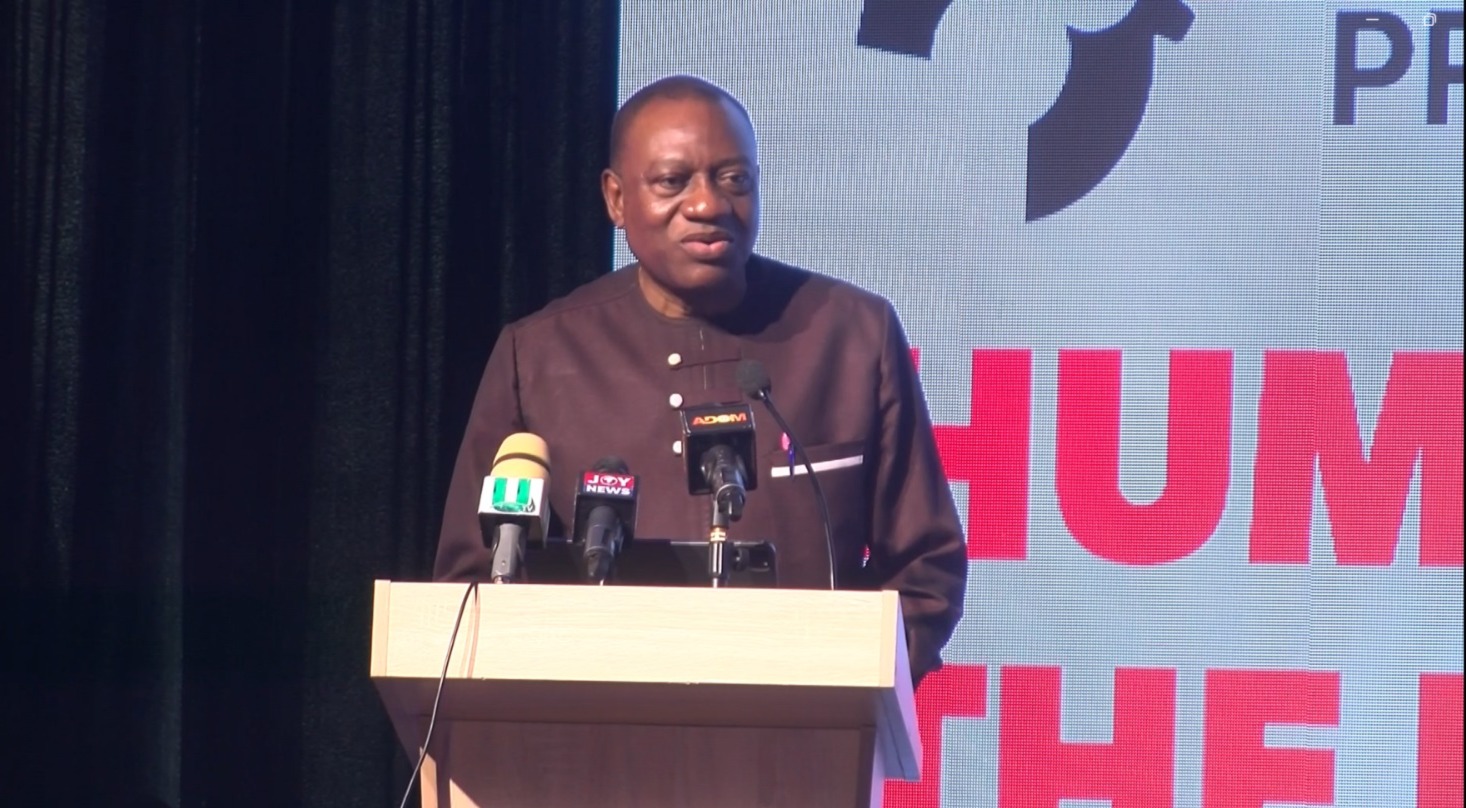

LONDON — “The blinking lights are a curse and a blessing at the same time for a lot of us,” Mandi Walls, developer advocate at PagerDuty, told the audience here at DevOpsDays London.

And, she added, “it doesn’t matter if they are representing good things or are representing bad things.”

If, as she defined it, an alert is something that’s “real time and demands your attention,” we are living in a time of alert fatigue. Developers need to push back on all of the push notifications, beeps, bells and whistles interrupting their flows.

A certain amount of firefighting comes with the job. But when is it really crucial to wake up devs in the middle of the night? This decision isn’t about the true emergencies. Teams need to address all the other calls, pages and pings.

At DevOpsDays London this month, Walls offered a framework to make sure these on-call “folks responsible for fixing and preserving customer experience” can be more productive and less stressed out. This is achieved with the right mix of service-level objectives (SLOs), automation and machine learning (ML).

At a time when fewer humans are involved in producing more code than ever, we owe it to our security engineers, sysadmins, site reliability engineers (SREs) and devs on call to get the most actionable alerts in real time. Here’s how.

Understanding the Immense Risk of Alert Fatigue

This deluge of unimportant alerts puts both your security and your employees at risk.

For the average organization, somewhere between 95% and 98% of alerts are noncritical or false positives, according to the “OX 2025 Application Security Benchmark” report. The same report also found that 84% of security professionals report burning out from alert overload, with one in three actively looking to leave their jobs in response to alert volume.

This isn’t an overreaction. Alert fatigue is the result of cognitive load and decision fatigue. Moshe Bar, a neuroscientist formerly at Harvard Medical School and currently at Bar-Ilan University, said on a webinar with OX that this fundamentally changes thinking patterns: “We become less creative, less exploratory. We exploit familiar templates and resort to easier solutions.”

The consequences of alert fatigue that Walls outlined are:

Delayed response times

Missed alerts

Ignoring false positives

Increased stress and burnout

Higher staff turnover

Decreased productivity

Lower quality incident reviews and documentation

Without time for post-mortems and reflection, the lessons get lost and incidents repeated. Walls referenced unnamed customers who work in operations that can have more than 100,000 alerts in a short time: “At some point, you’ve just got to declare alert bankruptcy. That’s no longer meaningful.”

Alerts are important, but so is not getting pinged with nonurgent alerts that distract from your real priorities.

Strategies To Reduce and Prioritize Alerts

At a time when we have more code — and hopefully more tests, monitoring and observability looking after it — teams have to be more organized and selective about what is waking them up at 2 a.m.

It may not sound fun, but if your team is facing a messy majority of nonactionable, nonurgent alerts, it’s time to prioritize cleanup. This can be time-intensive, Walls warned. Teams often need to intentionally block out a sprint to concentrate on cleaning up existing alerts.

Start with the noisiest alerts and then, she continued, revisit each alert signal, asking:

Is it actionable? Can I do anything right now? Offer data to help compel the product manager to fix it.

Is it urgent? “Admitting to yourself that not everything we run is a Sev-1,” Walls said, when it could just be a ticket.

Is it helpful? “We want to get to the point where everything that is coming in and alerting a human user is important to customer experience,” she said. These customers, she emphasized, should include your internal users, whether you are managing a human-resources tool or an internal developer platform.

Look to easily surface the alerts that “have real material impact to your business,” Walls said. “Even if you’re just supporting internal IT processes, especially if the alerts are coming from payroll systems, things that you want to have working as everybody likes to get paid, right?”

Methods to reduce alert fatigue:

Don’t alert on success. Nearly always, Walls said, you don’t need to know if something is working in real time — just let it work in silence.

Don’t send alerts that aren’t actionable. “This thing is broken without explanation” isn’t going to help it get resolved.

Set appropriate urgency and severity, deferring low-urgency alerts. “Takes a little bit of humility,” warned Walls, as there will always be features that engineers worked hard on but that are unpopular.

Delete or suspend broken alerts. There may be some lag between monitoring tools and what goes to production. Turn off alerts for things that aren’t up to date or are chronically broken.

AI can help identify what to deprioritize, because it’s very good at identifying patterns and categories of different types of alerts.

How To Ground Your Alerting Policy in SLOs

Next, Walls argues, alert policy should be tied to SLOs, which are always specific and measurable targets of performance, but, unlike service-level agreements (SLAs), remain an internal focus.

Tie your SLOs to your production metrics, grounding them in anything that matters to your external and internal users. Once you set your goals, communicate them to product managers in a way that helps them prioritize a feature, bug fix or update that is flagging a lot.

Walls gave the example of: “The users really like this component. How can we make sure this component is always up to what they want out of it?”

SLOs, she argued, give you the ability to ask, for every single incidence of an error: Is it worth notifying a human in real time?

“We want to have some wiggle room,” Walls said. “We want to have some tolerance for how many alerts in a certain time period represent a real problem, versus the internet being the internet today, and there’s something weird between monitoring and the service itself.

“We want to get to a place where we are sure that when the thing alerts to a human, there is a real problem that needs to be remediated, and the SLOs are going to help us do that.”

Be sure to calculate an error budget for your SLOs — often 95% of the time within tolerance, Walls suggested. This stands down your on-call team for the 5% of the time that things are spiking, but it’s not really an emergency — at least not yet. You can also, she recommended, change the volume of alerts by adding thresholds based on your error budget.

This practice, she said, also gives you wiggle room for the unpredictability within staging how your users will use a feature. This 5% gives you time to then monitor and observe how they are going to use it.

The overall goal of SLOs then becomes to reduce the number of alerts of what she called the “surprising stuff” that doesn’t reach the tolerance threshold, so you are only alerting things that are truly important right now.

Identifying When and How To Automate Alert Responses

Somewhere between 20% and 23% of PagerDuty alerts that pinged human beings were resolved within five minutes, said Walls. This means that almost a quarter of alerts didn’t require a deep triage or unusual handling. Those on call already understood what the alert was about and aren’t even learning from fixing it.

“Human resolution in under five minutes means that is a waste of people’s time,” Walls said. Thus, such alerts are ripe targets for automation, she said; they tend to be alerts for things in the architecture that you never get time to fix or modernize.

“We want to get to a place where we ask the machines to do this for us,” she said. “We want [the solution] to be triggered by the alert, so the humans don’t have to know.”

You can assign a metric to the AI agent based on parameters: for example, that it’s OK if it has to restart three or four times a week. But you don’t want it doing that 300 times.

You can write this automaton, Walls said, with a human in the loop for common issues related to novel alerts in our complex distributed environments. This can be, for instance, that the automation didn’t work, so then ping the human engineer to figure out why it didn’t work. This then becomes an actionable alert for the engineer, which stops the AI agent from repeating the error continuously.

Organizations will undoubtedly have a high volume of low-urgency alerts that automation can take care of. If you already have a RunThis.sh script for it, she said, you want to get rid of the human response completely.

A great AI use case is to leverage automation to preproduce information and telemetry to speed up response time, Walls said. This can be prepopulating a Slack channel with links to dashboards and to the data that appears in the logs. Be careful that these don’t just create more alerts, she cautioned, instead of helping to remediate them faster.

Practical AI Use Cases for SREs Today

About two-thirds of CISOs are planning to add AI-powered features to their security stacks within the next year, according to a 2025 report by DarkTrace. Where is AI helping now?

“The AI space in SRE over-indexes on incident response, which is boring,” Dave O’Connor, vice president of engineering at Astronomer, told The New Stack. “Don’t fight the fires faster.” Instead, he said, work on the signals to prevent future incidents.

You can ask AI, he said, “to analyze six to 12 months of our incidents and tell me what I’m doing wrong. Use these amazingly powerful analytical tools. They’re much better than humans” at uncovering patterns.

SREs and other security engineers have a lot of “stranded knowledge” — for example, how Prometheus works — which O’Connor also recommends feeding into a knowledge base with a chatbot overlay.

This and other AI SRE use cases require intentional data sharing and cleaning.

“I need to know if they are all related to a particular problem or cluster of problems,” Walls said, which makes intelligent alert grouping a great early AI SRE use case.

The problem, she warned, is that “alerts are usually terrible, so garbage in/garbage out.”

To add to this, alerts are usually owned by different teams on different platforms, maybe even in different clouds. SRE teams would benefit from cleaning up alert messages and even manually grouping them before feeding them into large language models (LLMs). This includes standardization around languages and the naming of services and deployed assets.

“When you have these tools available, they are incredibly powerful,” Walls said. “But you have to ensure your data is aligned to the point where this will actually work for you.”

Similar to O’Connor’s suggestion of knowledge dump and transfer, Walls also remarked how “the humans that work on the system probably know exactly how things are configured and what they talk to, and they have a mental map of the system diagram, [showing] what the AI model does and doesn’t know.”

You need to work with those people who work on those systems that can help translate that mental map for the AI.

A Checklist for Reducing Your Overall Alert Load

It benefits all tech organizations to stay alert to things that are meaningful, important and need human response right now. You also want every alert that reaches a human responder to be actionable, with few repeated alerts.

With this in mind, Walls created an SRE checklist:

Clean up alerts.

Focus on your users with SLOs and prioritize alerts on those metrics.

Get the junk out of the human workflow with automation.

Train the machines to be effective teammates.

Does this all sound expensive?

As Walls put it, “Missing alerts, having longer incidents, having more downtime or outages, reducing that overall customer experience is also expensive.”