Copyright independent

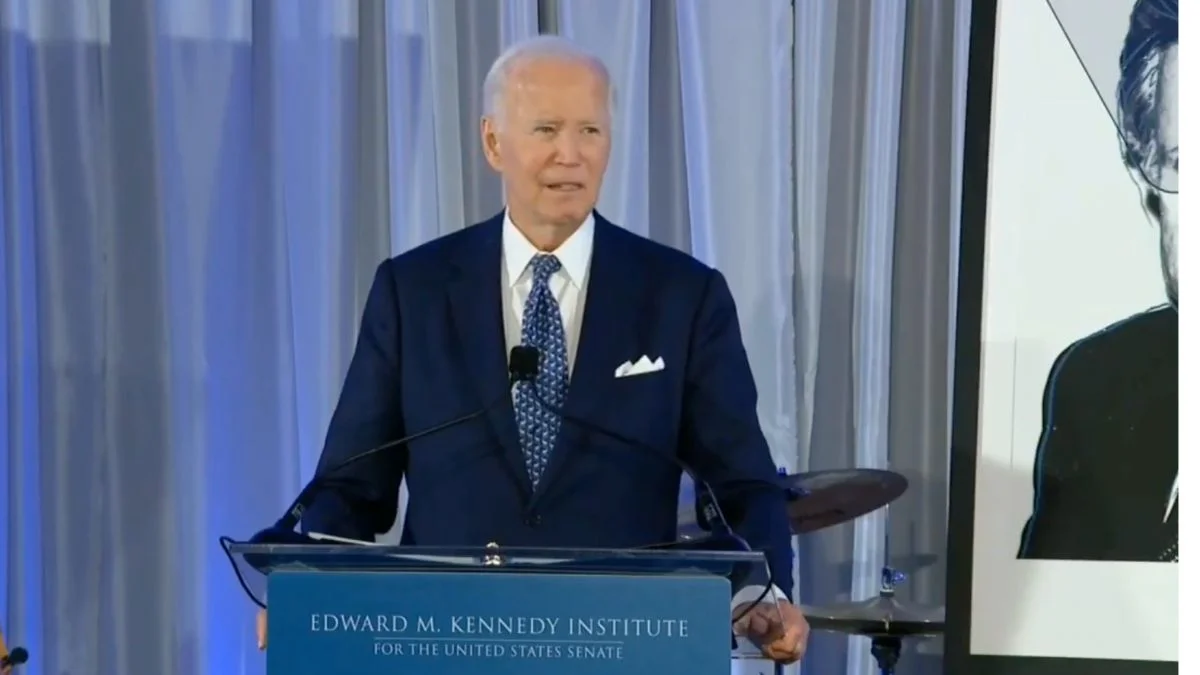

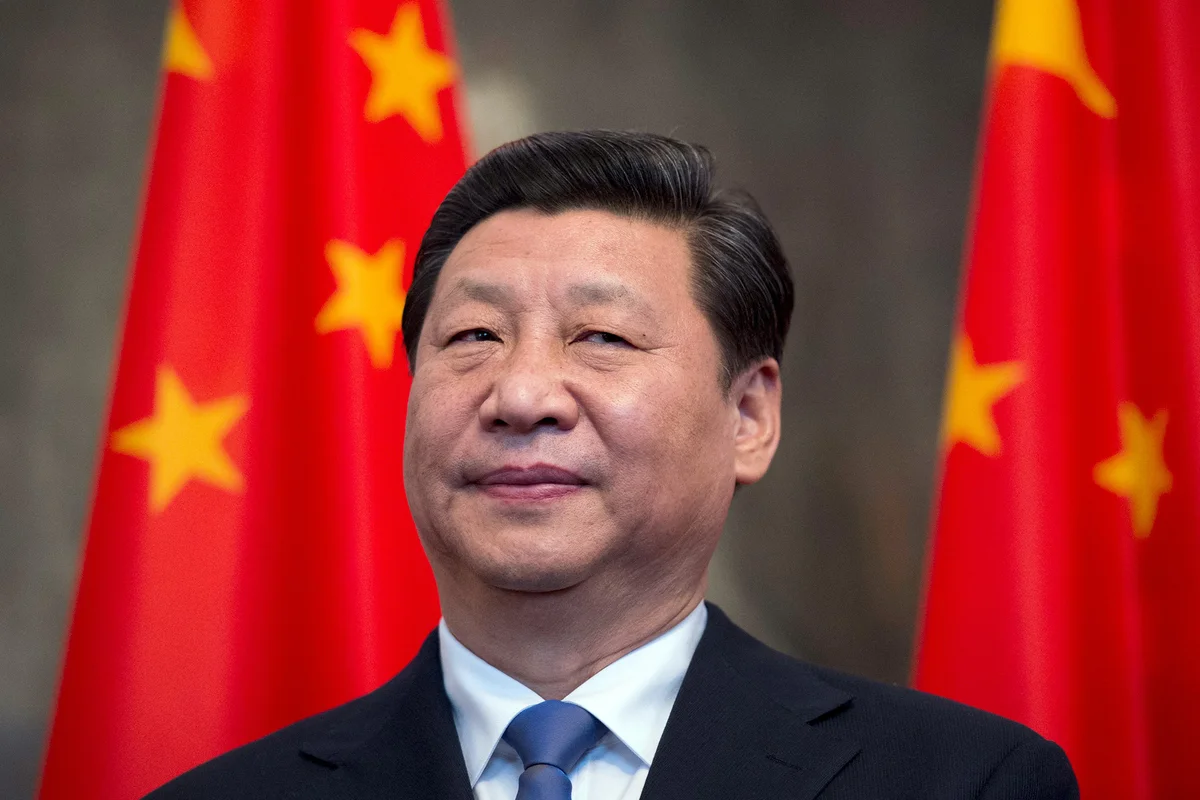

An unexpected grassroots football phenomenon, born from the fields and factories of rural China, is rapidly transforming the nation’s sporting landscape, drawing millions of fans and inspiring urban centres to launch their own amateur leagues. This burgeoning movement offers a glimmer of hope that China can finally cultivate world-class talent from the ground up, challenging its long-standing struggles on the global football stage. Despite boasting an estimated 200 million fans – more than any other country – China has consistently failed to produce top-tier teams. This has largely been attributed to a rigid, top-down system where professional clubs select players from a limited pool of pre-screened candidates. The professional game itself has been plagued by a history of match-fixing, corruption, and dismal performances, leaving President Xi Jinping’s ambition for China to become a football superpower by 2050 seemingly more distant than ever. However, 2023 marked a turning point with the remarkable success of the Village Super League (VSL). This amateur competition captivated audiences with its passionate matches, vibrant half-time folk performances, and unique prizes of livestock. Beyond the pitch, the VSL significantly boosted local tourism and economies, even earning praise from President Xi in his 2024 New Year’s speech. Grassroots football, he noted, "embodies people's pursuit of a beautiful life and presents a vibrant and flourishing China to the world”, marking the first and only time he has mentioned the sport in his New Year messages since taking office. The VSL’s widespread appeal has since encouraged major cities to embrace amateur leagues, hoping to replicate its commercial triumph. The response from spectators has been overwhelming. The final of the inter-city Jiangsu Super League (JSL) on 1 November, organised by the provincial sports bureau and 13 city governments, attracted 62,329 spectators. This figure nearly matched the record 65,769 attendees at a professional game in 2012. An additional two million people, unable to secure the 20 yuan (£2.20) tickets – a stark contrast to the 1,000 yuan often charged for Chinese Super League seats – streamed the final online. Overall, online viewership for the JSL’s 85 matches surpassed an astonishing 2.2 billion streams. Hours before kick-off, fans marched into the Nanjing Olympic Sports Centre Stadium, waving banners and coloured smoke sticks, chanting slogans in support of their home teams. Even supporters from the 11 cities that didn't reach the final turned out to represent their defeated sides. In a dramatic penalty shootout, the city of Nantong narrowly lost to Taizhou. This burgeoning amateur scene is also beginning to forge a new pathway to the professional game. Taizhou supporter Cai Liang, 39, admitted he had been hesitant about encouraging his son to pursue football. Yet, his 14-year-old son, whose interest was ignited after watching Taizhou defeat Zhenjiang in July, declared, "I'd play football more often." The professional game’s scandal-ridden reputation has traditionally deterred parents, who often prioritise academic paths for their children, from considering football as a viable career. Professional players have historically emerged from a very narrow state and national sports school system, meaning talent not evident at a very young age is often overlooked. The JSL’s success has inspired other provinces to follow suit, with Liaoning launching a league last year, Hebei and Inner Mongolia forming theirs in August, and Hunan and Sichuan kicking off theirs in September. There are already early indications that these amateur leagues are creating a direct route to the professional ranks. Taizhou midfielder Wu Zhicheng, 18, became the first JSL player to enter China's top professional division in July. When asked after a pre-match training session if more players would follow in Wu's footsteps, Taizhou coach Zhou Gaoping, the league's only female coach and a former player on the women's national team, expressed her optimism: "There will be players advancing to national teams." The Nanjing Olympic Sports Centre, once home to Jiangsu FC – a club that famously had former England manager Fabio Capello at its helm during the heady days of Chinese football's pre-pandemic gold rush – now hosts this new wave of enthusiasm. Backed by corporate cash, the Chinese Super League (CSL) once attracted world-class talent and coaches. Jiangsu FC even won the CSL in 2020 but ceased operations less than a year later after its owner, Nanjing-based retailer Suning Group, decided to refocus on its core businesses. "Jiangsu FC regretfully disbanded at its peak and now Jiangsu's hopes have been re-ignited by the amateur league," said Li Jianlin, 33, a Taizhou fan. "Chinese soccer still has a future."