Copyright scmp

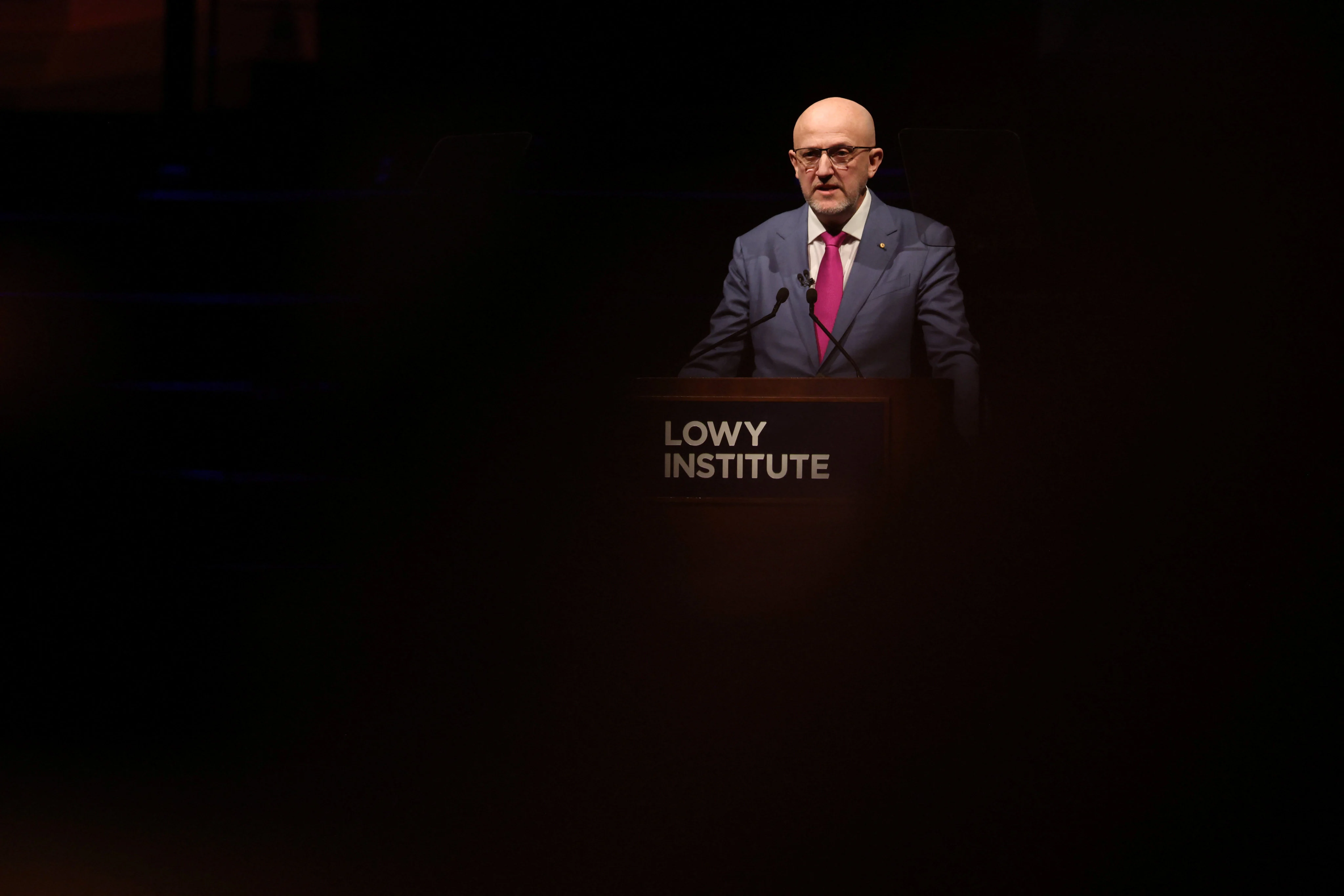

Regional hot-button issues amplified by great power rivalry, such as the South China Sea and Taiwan, have contributed to more Australians “than ever before” being exposed to foreign intelligence operations, Canberra’s top spy has warned. Australia’s social cohesion faced “unprecedented” tests, with international dynamics playing a role, Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) director general Mike Burgess said in a speech on Tuesday. The country had been among the targets of Moscow’s increasingly aggressive intelligence apparatus against Kyiv’s supporters worldwide following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, while the Middle East conflict had also reshaped Australia’s security environment from afar, he said when delivering the 2025 Lowy Lecture in Sydney. “Great power competition in our region is contributing to multiple territorial disputes, including in the South China Sea, Kashmir, the Taiwan Strait and the Korean peninsula, while also driving a relentless hunger for strategic advantage and an insatiable appetite for inside information,” the Australian domestic spy chief told the event hosted by the Lowy Institute think tank. “This is why, based on what ASIO is seeing, more Australians are being targeted for espionage and foreign interference than ever before,” Burgess added. His remarks came just hours after Australia’s defence minister Richard Marles called out Beijing over the South China Sea, where a mid-air encounter between a Chinese fighter jet and an Australian maritime patrol aircraft two weeks earlier led to both sides trading harsh accusations. Addressing an Indo-Pacific maritime exhibition in Sydney, Marles said it was becoming “increasingly risky” for the Royal Australian Navy to protect the country’s trade routes, particularly those through the South and East China seas. “The biggest military build-up in the world today is China, and that it is happening without strategic reassurance means that for Australia, and for so many countries, a response is demanded,” he said on Tuesday. Beijing has repeatedly said the South China Sea “is one of the safest and freest maritime routes in the world”. Marles’ comment coincided with the departure of Australia’s trade minister Don Farrell on the same day to lead a record delegation of Australian businesses to Shanghai to attend the China International Import Expo, which runs until November 10. “Through regular dialogue, the Australian Government is expanding engagement with China in areas of shared interest, while continuing to speak out on the issues that matter to Australians,” stated a government release on Tuesday regarding Farrell’s trip. Those statements and events this week are the latest to lay bare the dynamics of the China-Australia relationship: while bilateral ties have broadly thawed and stabilised during the past two years, recurring strains in security and defence domains still appear to be out of sync with warming diplomatic and trade relations. The divergence raised concerns among Chinese observers, who said the Albanese government’s efforts to improve the relationship with China could risk being undermined or sabotaged by Canberra’s defence and security sectors. On October 30-31, Australia took part in a joint patrol with the United States, the Philippines and New Zealand in the South China Sea. “Australia reaffirms the 2016 South China Sea Arbitral Tribunal Award is final and legally binding on the parties,” the country’s defence department highlighted in a release on Saturday. That referred to a case in The Hague nine years ago, which ruled that there was no legal basis for China’s sweeping territorial claims in the disputed waters, a result that Beijing dismissed as “illegal, null and void”. Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Southern Theatre Command said on Saturday that it had closely monitored the exercise last week, with all actions “seeking to stir up trouble in the South China Sea … under full control”. Nevertheless, Chinese Premier Li Qiang told Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese that Beijing saw that bilateral ties “have continued to show a positive trend” when the pair met in Kuala Lumpur on October 27 on the sidelines of the Asean summit. Albanese said Canberra stood ready to properly manage differences with Beijing and expand cooperation in fields such as trade, green economy, minerals, climate change, culture and people-to-people exchanges, according to Beijing’s readout of the meeting. But resource-rich Australia has still made efforts to walk a tightrope between its largest trading partner and one of its most important security allies amid the China-US rare earth tensions. That was marked by the multibillion-dollar bilateral critical minerals agreement signed by Albanese and his US counterpart Donald Trump at the White House two weeks ago, as well as a recent move by the Japanese trading house Sojitz to import rare earth elements produced in Australia in a bid to diversify supply chains outside China. In his speech on Tuesday, Burgess did not name China as explicitly as he had done in the past. In July, the Australian spy chief listed China, Russia and Iran as three of the main nations behind espionage in Australia as well as “many other countries”. When asked why he did not mention Beijing this time, Burgess said: “how do you know I wasn’t talking about things China did in my remarks today”. “We all spy on each other. But we don’t conduct wholesale intellectual property theft, we don’t actually interfere in political systems and we don’t undertake high-harm activity,” he said. His address to the Lowy event primarily focused on “things that tear at [Australia’s] social fabric”. “At the extreme end of that, that isn’t China,” he said in the question-and-answer session after directly naming Russia and Iran in his speech as threats. In the body of the speech, Burgess said that all three international drivers pressuring Australia’s domestic security environment – Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the Middle East conflict and neighbouring regional disputes – “are being accelerated by rapid advances in technology”. He characterised the internet as “the greatest incubator of grievance narratives and conspiracy theories,” which, he later added, were accelerated by social media and exacerbated by artificial intelligence. “I am deeply concerned about the potential for AI to take online radicalisation and disinformation to entirely new levels,” he said. “The result of these compounding dynamics is a domestic security environment with an unprecedented number of challenges and an unprecedented cumulative level of potential harm.”