For much of his life, death seemed to follow Steve Mandell.

In his early days, Mandell was, of all things, a Chicago vice cop. After being kicked off the force for insurance fraud, he used his police training to become a prolific robber, extortionist, drug dealer and, according to state and federal law enforcement, a cold-blooded killer.

Over time, the bodies piled up: A suspected informant executed in his car at a downtown intersection; Mandell’s own father found hogtied and shot in a trunk; A trucking firm owner fished out of the Des Plaines River days after telling his wife he was going to meet Mandell and never came back.

And then there was the case that landed Mandell in prison for life: a macabre plot foiled by the FBI in 2012 to kidnap and extort wealthy businessmen, then torture and dismember them in his own, custom-built killing chamber.

Last week, after spending a decade in one of the country’s highest security prisons, Mandell died of an undisclosed illness at a federal medical prison facility in North Carolina, according to the U.S. Bureau of Prisons. He was 74.

While never one of Chicago’s more high-profile mob figures, Mandell, who once went by the name Steven Manning, has a story that’s unique even in the city’s heavily chronicled underworld.

Not only was he the first former law enforcement officer to ever be sentenced to Illinois’ Death Row, he later became a celebrated exoneree and won a landmark $6.5 million judgment against the FBI for framing him — only to have the judge reverse the jury’s award.

His reputation for meticulous planning, along with a bipolar personality that could switch from charming to chilling in an instant, made Mandell a feared figure even among those used to dealing with some of the city’s more unsavory individuals.

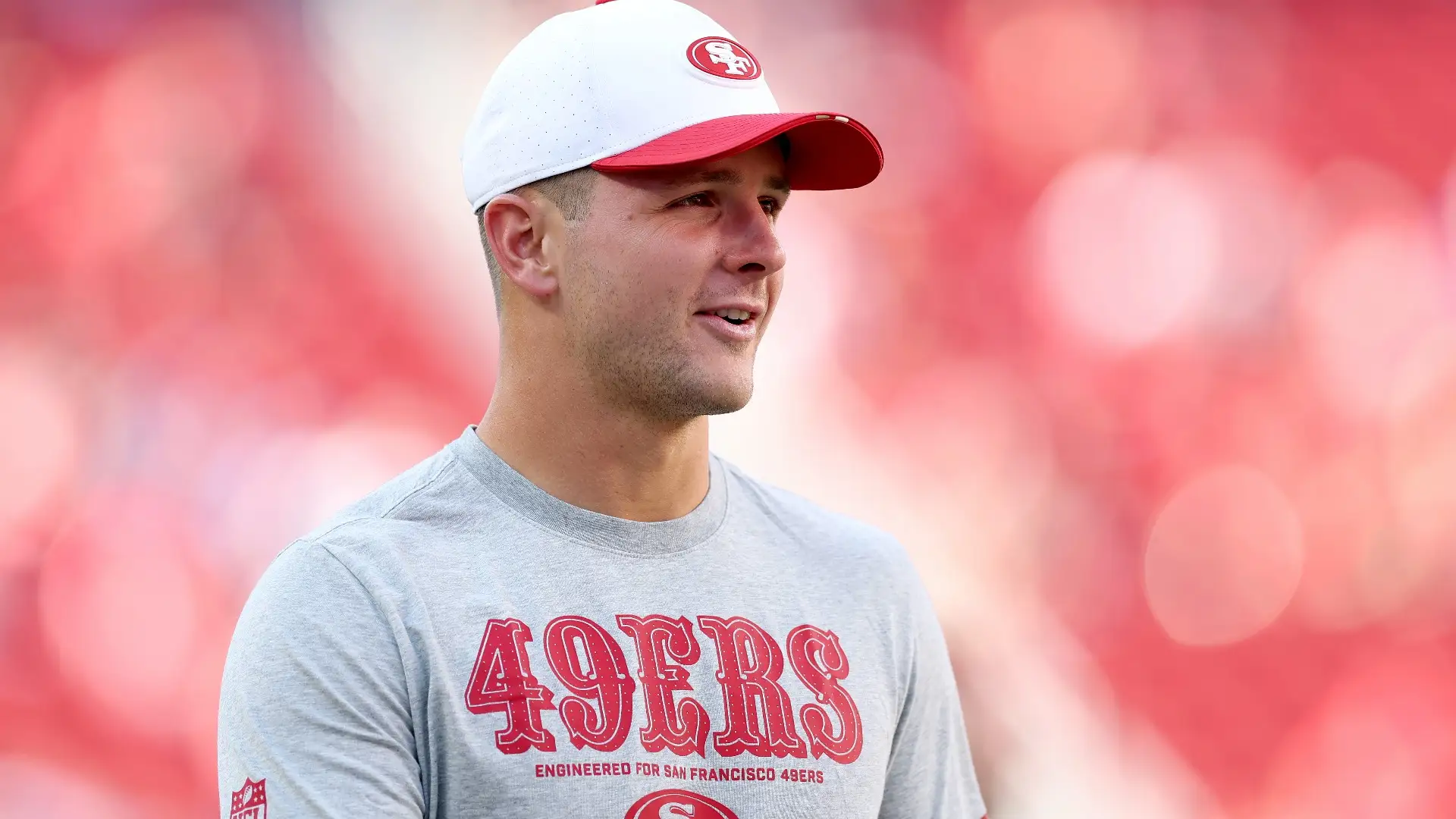

“This guy was scary,” said George Michael, the Northwest Side real estate magnate who worked undercover with the FBI to help bring Mandell down. “He spoke about death like most people would speak about the weather.”

After Mandell’s stunning arrest in October 2012, one former prosecutor told the Tribune he was “one of the most dangerous criminals I ever dealt with.”

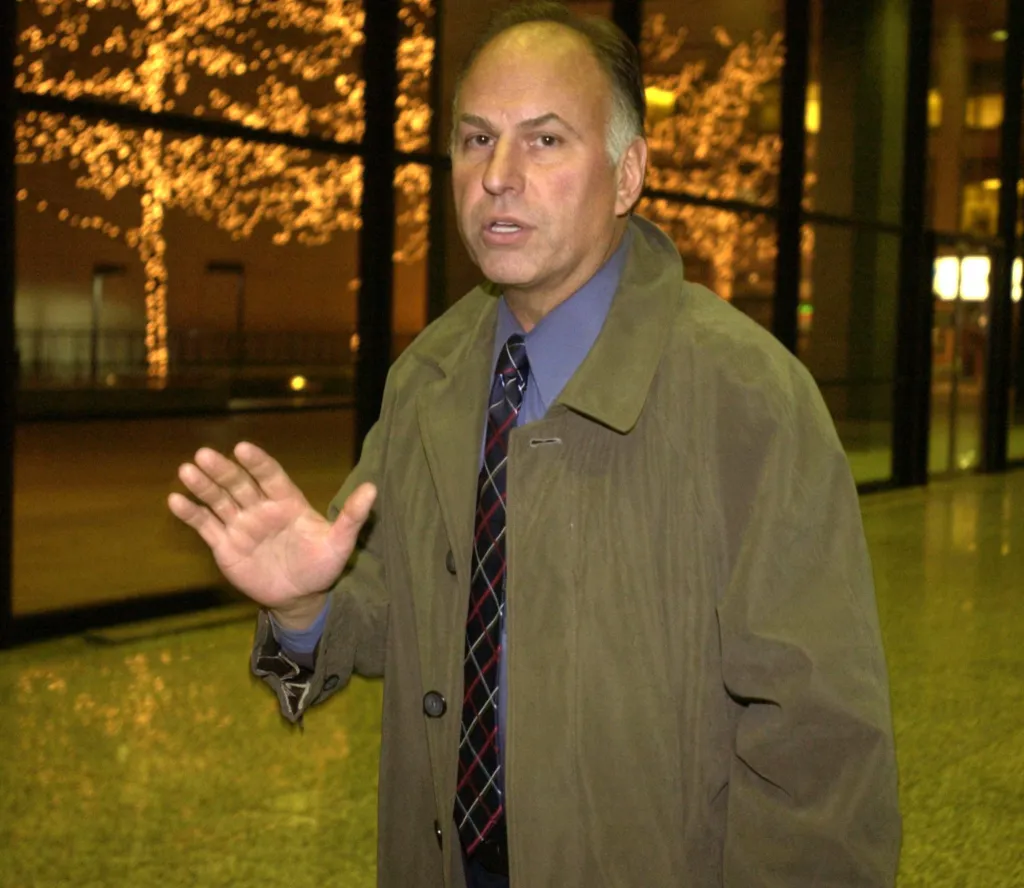

That sentiment was echoed Friday by Ted McNamara, the former boss of the Chicago FBI’s organized crime section who oversaw the operation that took Mandell down. Even McNamara, who investigated the top echelon of the Chicago Outfit, couldn’t believe some of the things Mandell said on tape.

“He was diabolical,” McNamara said. “If you went to a movie studio and said this is the basis of a movie they would laugh at you.”

Now that Mandell is dead, the full extent of his criminal activities will likely never be publicly aired. Among the unsolved crimes law enforcement believed he had a role in was the slaying of popular Italian restaurateur Giacomo Ruggirello, whose body was found in his still-smoldering Highland Park home at the same time Mandell was planning his torture chamber.

The Tribune reported a video camera hidden by the FBI in a picture frame at Michael’s realty office captured Mandell talking about the fire on the same day it happened, leaning in to Michael and asking, “Do you think they respect my work now?’”

Mandell was never charged with that crime, which is officially still an open investigation, according to Highland Park police.

Michael told the Tribune on Friday it was just one of many spine-tingling moments he had with Mandell as he tried to earn his trust.

“There are many other secrets that go with him to the grave,” Michael said.

Early days

Mandell was in his early 20s when he joined the Chicago Police Department, but the 10-year veteran resigned in 1983 after he was convicted in an insurance fraud scheme. He soon was linked to several burglary and jewelry theft rings in Chicago’s underworld.

In 1985, the Illinois State Police issued an internal criminal intelligence bulletin that listed Mandell, then known as Manning, as a known member of a crew that specialized in drug dealing, luxury auto theft, and burglarizing jewelry stores and coin shops, court records show.

The crew was made up of several former police officers, including Mandell and his longtime associate, former Willow Springs cop Gary Engel, who knew how to bypass complex alarms and were known to monitor police radio frequencies and even conduct counter-surveillance on law enforcement, the bulletin stated.

“Crew members are known to telephone law enforcement agencies and represent themselves as police officers in order to acquire information,” the bulletin stated. “They have also used the same method to enter police buildings unchallenged.”

Mandell was convicted of burglary in 1987 and sentenced to four years in prison. He also had worked at times as an informant for the FBI but quit that role by the time of his conviction, records show.

In 1990, after authorities received a tip from a reputed Missouri mobster, Mandell and Engel were arrested in Chicago and charged with taking part in the kidnapping of two Kansas City drug traffickers six years earlier. Both were later convicted; Manning was sentenced to life in prison and Engel 90 years behind bars.

While Mandell was being held in the Cook County Jail on the kidnapping charge, authorities used notorious jailhouse informant Tommy Dye to try to obtain a confession from Mandell to the killing of Jimmy Pellegrino, a drug dealer and trucking firm owner whose body had been discovered gagged and bound with duct tape, shot in the head and dumped in the Des Plaines River.

Dye secretly recorded Mandell, but the recording contained no admissions by Manning to the murder. However, Dye claimed Mandell had confessed to him during a two-second inaudible gap on the tape.

At trial, Pellegrino’s widow, Joyce, testified that her husband had told her as he was leaving for a meeting with Mandell “that if he turns up dead I should go to (the FBI)” and tell them that Mandell killed him.

In urging the judge to impose a death sentence, prosecutors linked Mandell to two other murders, including the 1986 slaying of his own father, Boris, whose body was found frozen in the trunk of his car at Hawthorn Center in Vernon Hills on March 10, 1986.

In addition, witnesses at the sentencing testified that two other underworld associates had gone missing around the time they were supposed to have met with Mandell.

Mandell was sent to Death Row, but both the kidnapping and murder cases later fell apart on appeal. “The only people to blame for this case is the FBI themselves,” Mandell told the Tribune on the day in 2004 that he walked out of a Missouri jail, free of both cases after 14 years in custody.

Mandell sued, claiming two FBI agents had fabricated evidence and coached Dye to falsely implicate Mandell in the jailhouse confession. In a surprise, the federal jury agreed that the agents had framed Mandell in the murder as well as the Missouri kidnapping and awarded him $6.5 million. However, a judge later threw out the damages, and Mandell never saw a penny.

William Gamboney, a former Cook County assistant state’s attorney who prosecuted Mandell in the Pellegrino case, told the Tribune in 2012 that investigators knew a dangerous person was back on the street.

“The feeling was he got away with something,” Gamboney said.

Recorded conversations

Mandell disappeared from Chicago for a spell after that decision, but within five years he was back on the FBIs radar, this time after he was introduced to Michael at a lunch meeting at La Scarola, an Italian restaurant on West Grand Avenue frequented by Chicago mob leaders.

McNamara, the former FBI organized crime boss, said Friday that most of the younger agents, who were investigating a Grand Avenue burglary crew at the time, didn’t know who Mandell was.

“I remember (my case agent) comes to me and says ‘Have you ever heard of this guy Steve Manning? One of my sources just bumped into him and he’s talking about doing all this stuff,’” McNamara said. “I said ‘Have him keep talking.’ It was amazing…We didn’t go after him. He just showed up.”

With Michael’s cooperation, investigators were able to capture Mandell on tape in his own words, discussing with palpable glee not only his plan to abduct and murder rich businessmen — starting with suburban real estate baron Steve Campbell, whom he jokingly referred to as “Soupy Sales” — but also a separate plot to kill a reputed mobster and take control of his piece of a lucrative Bridgeview strip club.

At the direction of the FBI, Michael found Mandell a Devon Avenue storefront to rent and helped him revamp it into a veritable torture chamber where bodies could be drained of blood and chopped into pieces — a location they jokingly referred to as “Club Med.”

In the recorded conversations, Mandell discussed his frustration with what he perceived to be weak and ineffective Outfit bosses, including Albert “Little Guy” Vena, identified in testimony as the reputed leader of the mob’s Elmwood Park crew.

“I’ll show you what Elmwood Park really looks like,” Mandell said to Michael on one video recording, making a slitting motion across this throat on the video. “I can get really nasty.”

On the night of Oct. 25, 2012, an FBI agent borrowed Campbell’s hat and Hawaiian shirt and drove his car to Michael’s realty office on North Milwaukee Avenue, where the abduction was to take place, according to trial testimony.

McNamara recalled a surreal moment as he and an FBI SWAT team were staged about a mile away near a Sports Authority parking lot. They were watching a live feed of the undercover video from Club Med, where Mandell and his accomplice, Gary Engel, the former Willow Springs cop, were sitting calmly, sipping on Dunkin Donuts coffee.

“This is literally like 45 minutes before they were about to go chop up this guy,” McNamara said. “Suddenly, Mandell says, ‘Ah (expletive ), I gotta go get a ski mask.’ So he leaves the location and drives to the Sports Authority…We are maybe 400 yards away from him.”

Soon after Mandell’s last-minute errand, he and Engel were arrested as they pulled into the parking lot in an unmarked Crown Victoria outfitted with police lights and scanners.

Inside the vehicle were zip ties, a bogus arrest warrant and pre-typed quit claim deeds for Campbell’s properties that they planned to force him to sign, the evidence showed.

When agents searched another one of Mandell’s vehicles, they found a drill that’s commonly used to crack into locks and safes as well as “bump keys” that burglars often employ to open doors without leaving signs of forced entry, according to trial testimony.

Next to that equipment was a folder marked “Investigative File” that contained the names of at least four wealthy people Mandell targeted for surveillance, including a real estate lawyer, the owner of a well-known grocery store chain, and shoe factory executive Chaim Kohanchi, according to testimony.

“It was only going to be the beginning for him,” Michael said Friday. “He had many, many people in his sights, and he was pretty excited about it.”

jmeisner@chicagotribune.com