By NIC MACLELLAN,Report 3

Copyright islandsbusiness

AS Pacific Islands Forum presidents and prime ministers hold their annual leaders retreat this Thursday, they’ll be briefed on regional engagement with donors and partners by a group of regional veterans – the High-Level Political Talanoa.

Partnership is a much-abused term, and it’s a vexed question for the 18-member regional organisation. Over many years, the Forum has granted Dialogue Partner status to 21 countries, large and small – and there’s a queue of candidates seeking this status.

This year in Honiara, however, Forum host Prime Minister Jeremiah Manele requested Dialogue Partner delegations to stay away from the annual summit. One objective was to provide time for extensive discussion of the Review of Regional Architecture (RRA) – a long-running process mandated by leaders, which will help define the ongoing relationship with other countries.

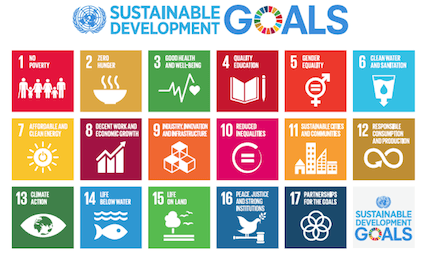

The RRA aims to ensure that the region’s agencies and process are fit for purpose, to implement the seven main themes of the Forum’s flagship policy – the 2050 Strategy for a Blue Pacific Continent. Given ongoing debates over Forum unity and the complex geopolitical environment, Forum foreign ministers stated last month that the RRA offers “both a strategic opportunity and a political necessity.”

The first and second phases of the review were finalised before last year’s Forum in Tonga, with analysis of the regional geopolitical context, and identification of possible improvement or rationalisation of the existing network of regional agencies. While the Forum is the Pacific’s policy and political hub, there are many other members of the Council of Regional Organisations of the Pacific (CROP), such as the Forum Fisheries Agency (FFA), the Pacific Community (SPC), the Pacific Tourism Organisation (SPTO), the University of the South Pacific (USP), the Regional Environment Program (SPREP) and more.

Work on the RRA has faltered, however, without consensus on the complex issue of relations with Dialogue Partners. In response, last year’s summit in Nuku’alofa initiated a political talanoa process to resolve significant differences.

The High-Level Political Talanoa group, who will report their findings on Thursday at the leaders’ retreat, has three members – all veterans of regional politics, and drawn from Melanesia, Polynesia and Micronesia.

Dr. Sir Jimmie Rogers of Solomon Islands served as Director General of the Pacific Community (SPC) between 2006-14. Peseta Noumea Simi of Sāmoa, is a long-time diplomat and, since 2015, Chief Executive Officer of Sāmoa’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Gerald Zackios, a former government minister and diplomat for the Republic of Marshall Islands, served as RMI’s Representative at the United Nations between 2016-2023. Zackios nominated—unsuccessfully—for the post of Forum Secretary General in 2022.

Outgoing Forum Chair, Prime Minister Aisake ‘Eke of Tonga, said the High-Level Talanoa process “will focus on listening to the views of our Leaders and reaffirming the Pacific as a region of deep dialogue, shared stewardship, and collective action. As we navigate complex global shifts, these conversations are central to ensuring our regional architecture remains fit-for-purpose and firmly grounded in Pacific priorities and values.”

With insights gathered from bilateral discussions with Forum member countries, the High-Level Political Talanoa group will now present their recommendations, framed around four key issues: political leadership and unity; membership; rationalisation of the Regional Architecture; and strengthened and deepened regionalism. Many will be welcomed by the Forum leaders, but watch out for some more controversial proposals that may ruffle some feathers!

Leaders this week will also receive feedback from a series of ministerial meetings this year, which have also considered the RRA. For example, the Forum Economic Ministers Meeting met in July, and discussed “the merits of adjustments to the regional architecture, including the consideration of alignment to international law, and emphasised that any reforms must reinforce regional unity and coherence. They underscored the need for strong mechanisms for consensus-building, political oversight and coordinated engagement on key political issues both within the region and with partners externally. Ministers also noted the importance of dialogue with external partners.”

Bad behaviour by partners

Over many years, participation at the annual Pacific Islands Forum has grown, with an increasing number of Forum Dialogue Partners, official observers and media, joined by delegations from civil society and the Pacific Islands Private Sector Organisation (PIPSO).

For civil society and citizens who wonder what concrete results come from the annual meeting, some worry there’s an element of circus in the expanding summits. Diplomats from the lengthening queue of Dialogue Partners often seek bilateral meetings with the busy island leaders (especially as some countries regard the Forum as a one-stop-shop, where Pacific presidents and prime ministers are all gathered in the same location, at the same time)!

This debate over partners is not new, nor solely related to the ongoing China-Taiwan dispute, as PRC diplomats seek to sway countries to shift diplomatic ties from Taipei to Beijing. Last year in Tonga, China’s special envoy Qian Bo was captured on video lobbying for changes to the Forum communique on Taiwan. However, as full Forum members, Australia and New Zealand have a home ground advantage when it comes to word-smithing the communique: they’re usually members of the drafting committee!

The annual China-Taiwan stoush is a distraction for harried Forum Secretariat staff, who waste a lot of time dealing with battered national pride. At the 2013 summit in Marshall Islands, the Forum Summit was held in a building constructed by Taiwan, which featured a large mural with a Taiwanese and RMI flag. When Chinese officials reused to walk past it, the offending flag was covered with crepe paper, then uncovered by increasingly frustrated staff.

When they met in Nauru in 2018, Smaller Island States worried that their own priorities could be pushed aside as Dialogue Partners brought their own agendas to the table. Noting the “increasing complexities of the geopolitical environment as well as the increasing interest of traditional and non-traditional partners in the Blue Pacific”, SIS leaders called for “the need to be provided the space and time to be able to discuss issues and priorities of shared importance.”

As leaders met with partners that year (with Nauru aligned with Taiwan at the time), a Chinese diplomat infamously stormed from the Dialogue Partners session. In Yaren, then Forum Secretary General Dame Meg Taylor told me: “This constant to-ing and fro-ing about Taiwan and China is a constant distraction.”

“The China-Taiwan stuff has been coming up since before I arrived,” Taylor said. “The issue that I would like to see is that the Pacific Islands Forum can protect this space for discussion of the issues that are important to the leaders of the Pacific, raised by the Pacific countries. I think that there will be a discussion at the leaders meeting on this, in terms of how development partners are treated across the board. There’s a need for a political settlement for the future.”

While Chinese officials have a reputation for undiplomatic diplomacy in the Forum, they’re not the only major power that leverages diplomatic pressure. In line with the tradition of American exceptionalism, US diplomats often ask for special treatment (At Forum 2018, the US delegation successfully pushed for a separate breakfast meeting with Forum leaders, rather than attend the full Dialogue meeting; in 2022, Fiji didn’t invite Dialogue Partners to Suva, but US Vice President Kamala Harris beamed in for a video speech – a privilege not extended to other partners).

Recently retired as the Forum Secretariat’s Director for Governance and Engagement, Sione Tekiteki also draws comparisons between the dialogue partners and the two largest Forum members, Australia and New Zealand. Writing in E-tangata, Tekiteki noted that “in practice, their size, foreign policy reach and legacy make them more akin to the Forum’s ‘dialogue partners.’ They provide aid, technical support, and act as the de facto guarantor of security and development arrangements. They even frame their participation in the Forum in the language of partnership – a word that glosses over the power imbalance.”

Engagement with overseas players is a growing problem, given there are another six nations queuing up to obtain Dialogue Partner status (Israel, Saudi Arabia, Ukraine, Denmark, Ecuador, and Portugal), each with their own agendas. The Forum Foreign Ministers Meeting in August 2023 proposed that as a criterion for obtaining FDP status, applicants should make a financial contribution to the region’s new Pacific Resilience Facility. At the Cook Islands Forum that November, Pacific leaders deferred all applications until the completion of the RRA.

Keeping out the partners

And here we are today. This year, the Solomon Islands government decided to restrict the Honiara summit just to Forum members, without the Dialogue Partners. This prompted private and public rebukes, with Australia, New Zealand and the United States chastising the host government, and the remaining three Taiwan allies – Palau, Tuvalu and Marshall Islands – suggesting they would not attend (although they’re all in Honiara this week)

Speaking at the RMI parliament on 4 August, Marshall Islands President Heine stated: “I believe firmly that the Forum belongs to its members, not countries that are non-members, and non-members should not be allowed to dictate how our premier regional organisation conducts its business.”

She noted that the Form is “the only avenue where we, as Pacific leaders, engage collectively with our development and dialogue partners in support of urgent and shared regional priorities. To delay these dialogues at such a critical time – when global attention, funding and cooperation are essential – would be a significant missed opportunity for both our Forum and our region.”

President Heine followed this speech by writing to the Forum host on 8 August, urging the Solomon Islands Prime Minister and the Forum Secretariat “to reconsider this approach and explore a more balanced path forward – one that allows us to preserve the momentum of regional cooperation, uphold the Forum’s legacy of inclusivity, and avoid the unintended consequence of distancing partners at a pivotal time.”

Under Labour governments, New Zealand usually plays soft cop, leaving it to Canberra to play the bad guy (think Scott Morrison’s performance at the Tuvalu summit in 2019, where the leaders retreat dragged on for 12 hours). But under the current Luxon government, NZ Foreign Minister Winston Peters has swapped roles.

Over the last year, the veteran NZ politician has displayed a feisty attitude, playing regional bad cop with a number of Forum leaders (from disputes with Cook Islands Prime Minister Mark Brown over China relations, to public criticism of Kiribati President Taneti Maamau over delayed meetings). Last week, it was Jeremiah Manele’s turn, as Peters criticised the Forum host nation for the decision to restrict the presence of Dialogue Partners this week.

“The blame lies squarely with the decision by the Solomon Islands government, who knew that over the years and decades, we’ve invited dialogue partners to come along because it expands our capacity, and… for the first time… they’ve said they don’t want to invite anyone,” Peters told RNZ. “Had we known that, the question is whether we’d be having it in Honiara next week, or in some other country where we can get dialogue partners to be interested. We need their help.”

Despite Winston Peters’ concerns, on 14 August the Forum Foreign Ministers Meeting re-confirmed the host nation’s decision. Some Solomon Islands officials have spoken out about the challenges and opportunities of dealing with the strategic tensions between the United States and China. In an article for Devpolicy, Derek Futaiasi wrote: “Many Solomon Islanders feel frustrated by persistent pressure to choose between development partners given uncertainties about commitments, including contradictions around the implementation of US financial promises and other engagements.”

Speaking to church and civil society leaders in Honiara this week, many think the decision to limit the size of the Forum isn’t a bad idea.

General Secretary of the Pacific Conference of Churches Reverend James Bhagwan told Islands Business: “I think the incoming chair of the Forum, the Prime Minister of the Solomon Islands, has been quite wise. I see this as an act of Pacific self-determination: this is a space now for the Pacific to talk.”

“I know there are those who would wish to be here, but this is now really a Pacific Islands Forum,” Bhagwan said. “Our leaders will have no distractions (apart from what civil society and the media bring to them, but we hope that adds to their conversations). I hope that this coming week is a space where Pacific leaders can focus on the Pacific, on one another. Umi tugeda act now – that’s the theme.”

Speaking to journalists in Honiara, Forum Secretary General Baron Divavesi Waqa also noted: “Even though there are some changes in the setup this time, I think we have to regroup, reset ourselves. I’m confident the meeting will be taken through day by day until the Leaders’ Retreat and will be successful without our dialogue partners.”

“Without the partners, the meeting will continue,” Waqa said. “It’s not going to change much because, as you know, partners have bilateral arrangements with individual countries anyway. These are the more active partners – they will continue to work with the Forum as well.”

However the Secretary General had soothing words for partners in the lead up to next year’s summit, to be hosted in the Republic of Palau: “I’m not saying that we don’t need them. We need them. And they’ll be back next year in Palau.”

Review of Regional Architecture

The current debate about dialogue partners is complicated by their diversity. Some provide large amounts of development funding; others are smaller donors but provide valuable niche contributions, technical assistance or diplomatic networks. Some fully support the region’s strategic plans and priorities, set out in the 2050 Strategy; others pretend they do, but spend most of their time focussed on competition with perceived enemies.

Recent discussions about the RRA have proposed a tiered system for Dialogue Partners, recognising that some are active players in the region, while others just value diplomatic ties with the PSIDS bloc in the United Nations. The stumbling block is that – like football – everyone wants to be in the premier league, and no one wants to get relegated to the second division.

For months, the High-Level Political Talanoa group has been doing the rounds to get feedback from Forum members. They’ve asked how to define partnership, and what criteria should be recommended or required to obtain formal partnership status.

There are no easy answers. For example, how can the United States be regarded as a credible partner when, on issue after issue, current US policy undercuts the region’s 2050 Strategy?

The Trump administration’s withdrawal from the Paris Agreement on Climate Change is a major blow to regional and global climate action, but the list of setbacks is never-ending: the closure of the USAID office in Fiji; funding cuts to other agencies that support valuable programs across the region, from the Federal Emergency Management Agency to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and Centres for Disease Control. Then there’s the executive order authorising deep sea mining beyond national jurisdictions, effectively bypassing the UN’s International Seabed Authority. And the bizarre “Liberation day tariffs” on Pacific states that hardly export to the US. And the announcement – later rescinded – of travel bans on Tonga, Vanuatu, and Tuvalu. And the next Presidential elections are years away…

Beyond Honiara, Forum island countries will continue to face pressure to choose sides in a climate of strategic competition. The one positive sign is that island states have continued to mobilise for their own agenda – the successful campaign to seek an advisory opinion on climate change from the International Court of Justice (ICJ) highlights Pacific both agency and diplomatic smarts.

And if partners really want to cosy up to the Forum, I’m sure the new Pacific Resilience Facility would welcome a contribution!