“We are cutting spending across the school and focusing our resources on our highest priority research,”Andrea Baccarelli, the Chan School’s dean of faculty and a renowned environmental health researcher, said in a statement. “That has been a painful process, as we have had to lay off highly valued colleagues and shut down important science, but it is the responsible thing to do.”

Harvard is currently negotiating a possible settlement over the Trump administration’s claims it tolerated a climate of antisemitism on campus. But the nearly $3 billion in federal grants and contracts the White House terminated in the spring took an outsize toll on the public health school, which relies heavily on outside funding and has the smallest endowment of any of the university’s 12 schools.

A spokeswoman said the school could lose as much as half of its federal grants because of changes in federal research priorities away from public health and anticipated steep reductions in reimbursements for so-called indirect costs, such as utilities, rent, and administrative staff.

The Chan School has laid off what the internal memo characterized as “significant numbers of staff” in administrative positions and was expecting to cut even more of those jobs. Harvard declined to detail the size or scope of those layoffs.

Among the studies that have been halted are one that sought to unravel the mysteries of tuberculosis and a clinical trial in Tanzania on the use of an inexpensive zinc supplement to help babies who contract neonatal sepsis, an often deadly infection.

The Chan School of Public Health operates on approximately $400 million in revenues from federal and state governments, foundations, corporate sponsors, and nonprofits such as the American Cancer Society, as well as tuition and fees. In July, an internal memo circulated to faculty described the financial plight in stark detail: the $200 million lost in federal funding not only accounted for 46 percent of the school’s budget, but also exceeded the school’s $150 million reserve, which is set aside to plug budget gaps.

“The School is facing unprecedented financial pressures,” said the memo, which has not been previously reported. “We do not anticipate that this will be resolved within a year.”

The Trump administration, led by Secretary of Health and Human Services Robert F. Kennedy Jr., has upended the federal government’s deep role in public health, undermining long-established and scientifically supported practices such as vaccinations, and fueling skepticism of experts. Baccarelli, the faculty dean, was drawn into the controversy this past week when President Trump cited his research to suggest a link between autism and women taking Tylenol or its generic equivalent, acetaminophen, during pregnancy.

Baccarelli’s findings have been questioned by other experts as well as in a court case in which he was hired as an expert witness. In a statement issued before Trump’s remarks, Baccarelli said, “Further research is needed to confirm the association and determine causality, but based on existing evidence, I believe that caution about acetaminophen use during pregnancy — especially heavy or prolonged use — is warranted.”

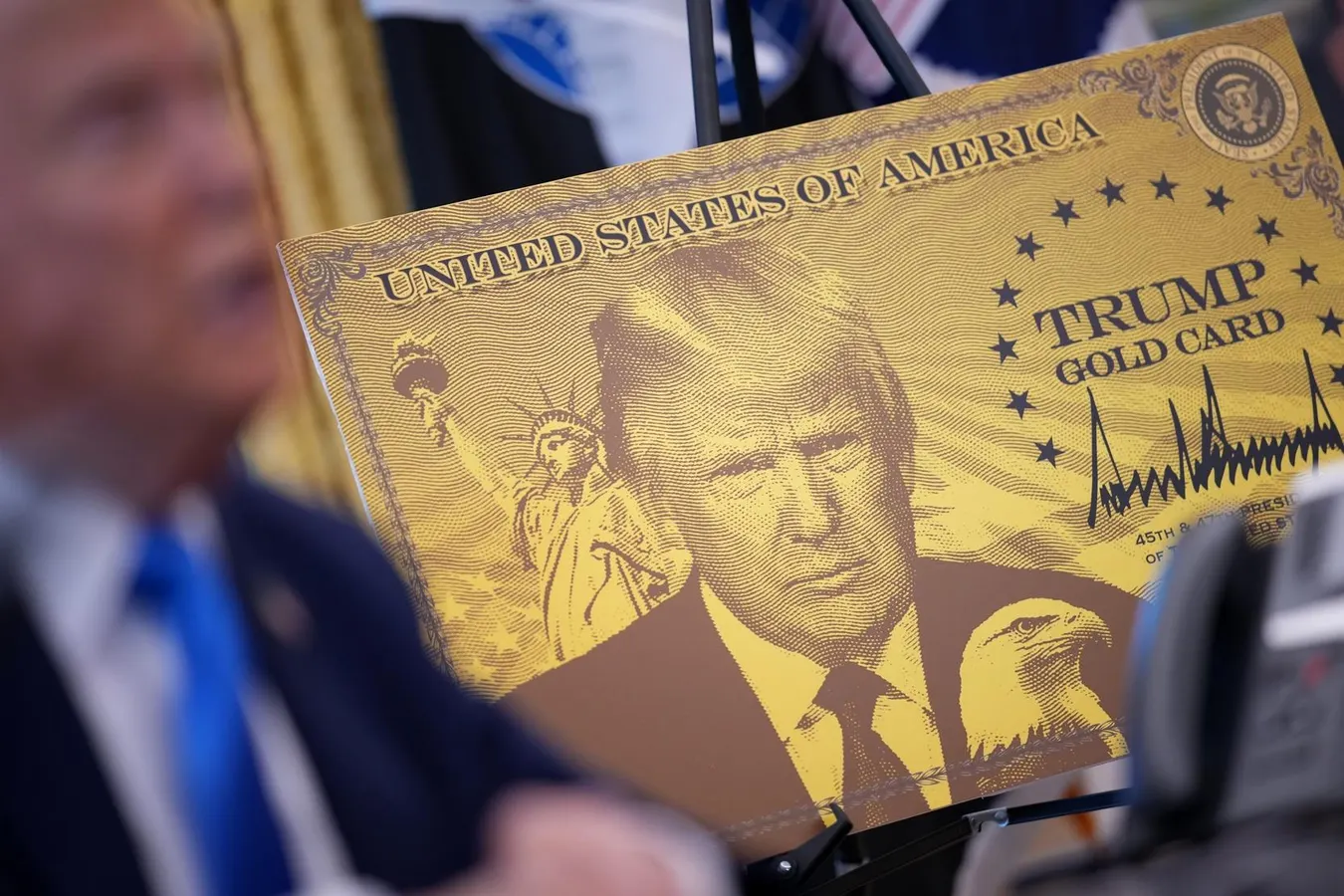

A White House spokesperson, Kusha Desai, said the United States remains the largest funder of scientific research in the world but “will not tolerate funding research of universities that fail to protect their students and allow discrimination to plague their campuses for years.” The Trump administration has accused Harvard of condoning antisemitism on campus during protests of Israel’s war in Gaza — a claim Trump’s critics call a smokescreen for attacking the university — and fostering “woke” ideologies.

PhD students are a vital part of a research institution, but the cutbacks have forced the Chan School to reduce the number of new students this year by nearly half, to 37 from 65. Also, the spokeswoman said the school recently notified three tenure-track junior faculty thats they face termination in 12 months unless funding materializes — an action veteran faculty members described as unprecedented.

The Chan School spends about $100,000 per PhD student per year, including health care benefits. In the past, the school primarily relied on federal training grants to fund those slots, but one or two PhD candidates were typically supported by companies such as drug makers Pfizer and Vertex, the Chan School spokeswoman said.

But now, she said, the Chan School has made it a priority to ask companies to fund PhD or postdoctoral slots. She said the school is in “active conversations” with at least half a dozen companies about sponsorships of doctoral candidates.

Timothy Leshan, spokesman for theAssociation of Schools and Programs of Public Health, said he was unaware of other public health schools seeking corporate sponsors for PhD students. But, he added, the Chan School could prove a harbinger in the Trump era.

“All of our schools are realizing they have to be creative in making sure their programs continue,” he said, “and we have the next generation of leaders in public health.”

Arthur Caplan, founding head of the Division of Medical Ethics at New York University’s Grossman School of Medicine, said drug companies have sponsored students seeking master’s degrees in his program. The companies get a pipeline to potential employees and cachet for helping to educate students when they sponsor graduate study.

If the Chan School relied more heavily on corporations to pay for the education of PhD candidates, it would be critical for the companies to agree to play no role in setting research priorities that might benefit their businesses, Caplan said.

The Chan School spokeswoman said such corporate sponsorships are “rigorously vetted.”

As it became clear in late spring that Harvard University’s fight with the Trump administration would drag on, the university cobbled together about $460 million from reserves and loans to help preserve research and programs.

Some Chan School faculty say that’s not enough. One faculty member, who requested anonymity because of the sensitivity of the topic, urged Harvard to dip further into its $50 billion endowment to save jobs — and research — at the Chan School.

“I would have loved to see the [Harvard] administration come out and say, ‘Public health may not be a priority for the Trump administration, but it’s a priority for Harvard.’ We haven’t seen that,” the faculty member said. “Harvard is sticking to its longstanding policy of allowing the schools to fend for themselves financially. But the effect of that is retreating from the defense of public health.”

The university has said the endowment can’t be used like a bank account, because, among other reasons, donors place restrictions on how their money can be spent.

As a result, researchers at the public health school now face Hunger Games-like scenarios as department heads decide which research should be prioritized and which junior faculty are expendable.

One Chan School professor, who asked to remain anonymous because of the sensitivity of the issue, said it would be terrible to lose faculty. But the greater loss would be to science and innovation.

Over the years, researchers at the school of public health have made groundbreaking discoveries, such as a cheap and easy way to treat cholera, dysentery, and other diarrheal diseases that is credited with saving millions of lives around the world. Researchers there also were the first to quantify the health risks of fine particulate air pollution, which led to stricter air quality laws credited with saving thousands of lives.

“It’s all the science that is not being done, it’s so heartbreaking,“ said the tenured professor. ”All the things that affect people’s lives.”