Copyright Pitchfork

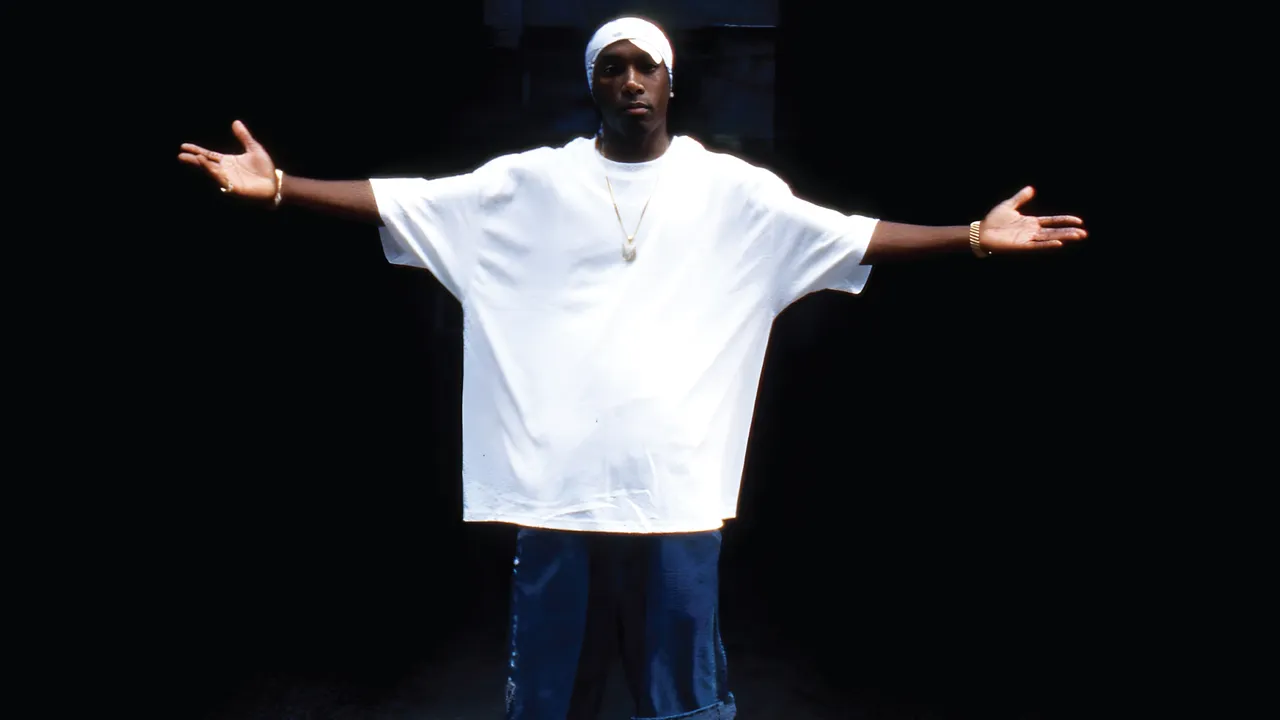

You could hear in his voice that Big L knew he was destined to become a legend. Beneath the hunger, the anger, and the near-frantic aggression was the unshakeable confidence of the kind of person who slides on sunglasses while strolling away from an explosion. L had a preternatural talent, his slick, smarmy flow sluicing over beats, each verse a knotted rope of multisyllabic rhyme schemes and disturbingly clever punchlines. He was a heat-seeking missile, a force that left craters in freestyle sessions and struck fear in other rappers’ hearts. Nas is on record saying as much: “Big L scared me to death. When I heard that on tape, I was scared to death. I was like, ‘There’s no way I can compete if this is what I gotta compete with.’” Born Lamont Coleman in 1974, the young Harlem MC rose quickly and burned bright. He joined Diggin’ in the Crates in 1991 as a teenager, signed with Columbia in ’93, and released his first album, Lifestyles Ov Da Poor and Dangerous, to critical acclaim in 1995. L was on the cusp of becoming New York rap royalty, getting cosigns from and trading verses with Jay-Z, touring Europe with O.C., and earning the adoration of nearly every DJ, radio personality, and culture carrier in the city. As the hype around his nascent career grew, L started a label, Flamboyant Entertainment, and began work on his second album, The Big Picture. There was talk of him signing to Roc-A-Fella. All signs pointed to a lengthy, storied career. Then, on February 18, 1999, L was killed in a drive-by shooting near 139th Street and Lenox Avenue, the area he referred to as “The Danger Zone.” He was 24. The posthumous record is a tricky, seldom successful endeavor. Big L’s first posthumous record, The Big Picture, was a rare exception, benefitting from the fact that he’d been working on it for two years before he passed. It was polished and nearly seamless; the guest appearances felt natural, the tone consistent. But L was young and didn’t leave an enormous vault of material. There’s a trove of his radio freestyles, but almost all have been circulating on Soulseek and YouTube for at least two decades. Whatever was left of his archive was picked over, remixed, or cut-and-pasted into “new” songs on 2010’s 139 & Lenox and 2011’s The Danger Zone. Harlem’s Finest: Return of the King, Big L’s fourth posthumous record, and the latest entry in Mass Appeal’s Legend Has It series, shows that the well is running dry. It’s a tonally confusing collection that sometimes scans as reverent homage but often comes across as hollow and perfunctory. One of the strangest things about Harlem’s Finest is how out of time it feels. The production team, overseen by Big L’s estate and Royce Da 5'9" (whose connection to L, aside from a stylistic influence, is unclear), doesn’t hone in on a specific sound. Though he made music for less than a decade, L came up during a rapidly shifting rap landscape, as prevailing styles morphed from the jazzy, sample-collaged boom bap into the jiggy era’s sleeker, more opulent sounds. There’s a haphazard attempt here to reference the entirety of the ’90s without digging into what made its movements interesting, giving Harlem’s Finest the vibe of an iTunes playlist cobbled together from bootlegged MP3s. Some choices work, like the glowering, Conductor Williams-helmed “Fred Samuel Playground,” which underscores how formative L’s music was for rappers like Rome Streetz and Conway the Machine, or “How Will I Make It,” a classic New York breaks-and-basslines jam which sounds rescued from the Lifestylez sessions’ cutting-room floor. But rote noir-rap beats like “u ain’t gotta chance” and “Doo Wop Freestyle ’99” are limp and two-dimensional, drained of all color and pizzazz. Almost every song has multiple producers, and you get the sense that these tracks were crafted by a remote email committee. Then there’s the issue of L’s vocals. Many of his verses are lifted from radio freestyles, necessitating some audio trickery to strip out the background and create usable a capellas. This gives them an uncanny character, full of the watery top-end you get from a screen recording, as on “u aint gotta chance,” or muffled and distant, like the verse used for “Grants Tomb ’97.” It’s distracting, especially when Nas or Joey Bada$$ come in, sounding expensive and sitting pristinely in the mix. Lyrically, L is mesmerizing, frozen in time at the peak of his technical powers. What felt cutting edge in ’95 is still razor sharp 30 years later; aside from some era-specific tells that range from funny (“My clan plans to get Giuliani hung” from “7 Minute Freestyle”) to wincingly brutal (the not-infrequent use of the F-slur), the uninitiated might think Big L was currently active. He raps circles around every guest, all of whom (save Method Man and Herb McGruff, who both spit vigorous, spry verses, and Errol Holden, whose solo track “Big Lee & Reg” is clear-eyed and chilling) seem unsure of themselves, happy to be on a track with an icon but confined by this narrow view of L’s oeuvre. If you’re already a fan, you’ve likely heard almost every verse here, either from low-quality rips or on another posthumous L record. It’s intriguing to listen to him on more modern production, but most of it is too indistinct to hint at where he could have gone. If you’re new to Big L, you won’t leave with a profound understanding of his artistry; Harlem’s Finest is more of a showcase for his pyrotechnics than the depth of his songwriting. There are some bright spots—it’s a genuine joy to have a high-quality recording of “7 Minute Freestyle,” L and Jay-Z’s breathtaking 1995 back-and-forth on the Stretch & Bobbito show, and “How Will I Make It” is an excellent example of L’s ability to blend catchy hooks and dead-eyed nihilism. But the misfires are rough. “Forever,” the Frankensteined Mac Miller “collab,” is both saccharine and grotesque, naked anemoia bait that makes hackneyed use of the Honey Drippers break. The single-verse, unfinished-sounding “All Alone” casts itself as the record’s ladies’ jam (something L might have scoffed at), but its sunny beat and R&B hook butt heads with L’s disconsolate lyrics. The question becomes: Why does this exist? In the mid-2010s, Donald Phinazee, L’s older brother and curator of The Danger Zone, sold the rights to that album and The Big Picture as well as L’s rhymebooks. Mike Herard, who heads L’s estate and helped put The Big Picture together, sees Harlem’s Finest as a means to secure the rights to all of L’s other recordings, specifically his freestyles. It reportedly took eight years to staple this record together, but the results feel so inorganic that it’s difficult to gauge how it expands L’s legacy. A compilation of those freestyle appearances would be more revealing of his explosive technique and livewire presence, but here, yanked from their original context, they feel thin and vacant. The posthumous releases now vastly outnumber L’s original output, and all overlap slightly, which risks diluting his initial impact. Big L was a phenom who left an indelible mark on hip-hop history, but Harlem’s Finest doesn’t find a new way to tell that story.