This week’s Ryder Cup at Bethpage Black is certain to produce the passion that has defined the competition since its inception in 1927 and laid out in Hank Gola’s new book, Ryder Cup Rivals. In this excerpt, Jack Nicklaus and Tony Jacklin play out the par-five final hole that ended with The Concession at Royal Birkdale in 1969.

From Ryder Cup Rivals by Hank Gola. Copyright © 2025 by the author, and reprinted with permission of Tatra Press.

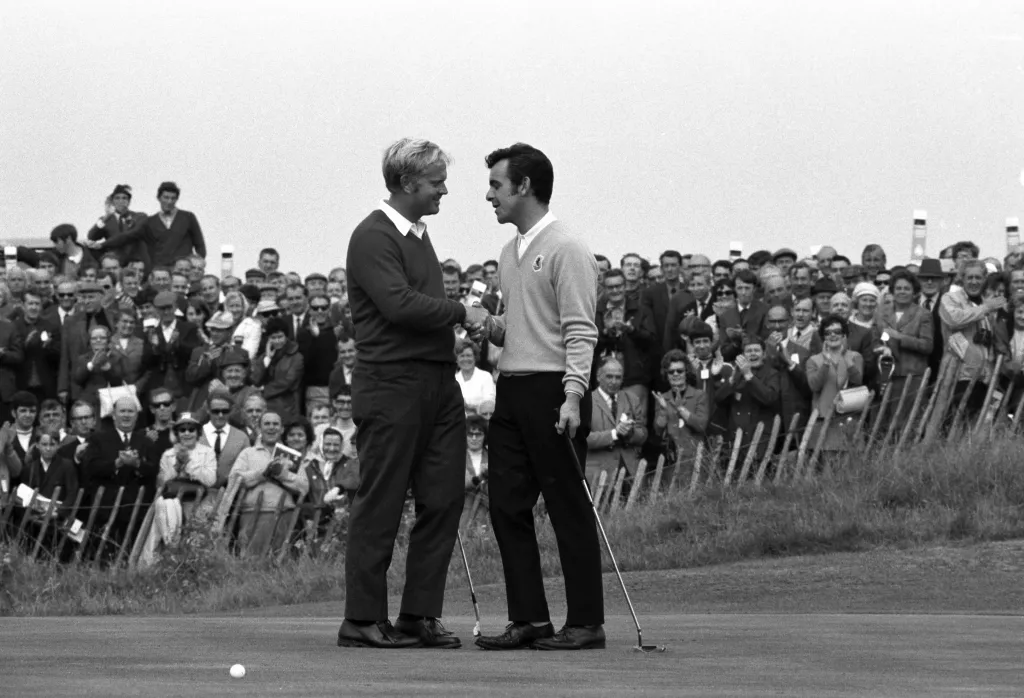

Thousands circled the final hole to watch Nicklaus and Jacklin play out what Jacklin called “an unenviable situation.”

Each man hit a 3-wood off the tee and Jacklin, probably out of nerves, jumped ahead as he started down the fairway. Nicklaus hollered after him, “Tony.” Jacklin waited for him. Nicklaus put his hand on his friend’s shoulder.

“Are you nervous?” he asked him.

“Hell, nervous? I’m petrified,” Jacklin said.

Nicklaus smiled. “I just thought I’d ask,” he said, “because if it’s any consolation I feel the same way you do.”

The exchange calmed Jacklin down. It was another example of Jack’s sportsmanship. But now a nervous Eric Brown, the British captain, was making his way back down the fairway toward Jacklin. “You know what you’ve got to do?” he asked in his thick Scottish brogue. Ironically, Jacklin and Brian Huggett were the two players that Brown had chastised when they reported late to the team hotel on the first day. Jacklin may have been thinking how much that didn’t matter now.

“Yes Eric, I know what I’ve got to do,” he said. With the wind in their favor, reaching the green in two wasn’t a problem. Nicklaus hit first and Jacklin responded, roughly equidistant at about twenty feet, from different angles. The gallery had rushed onto the fairway and had to part to let the two competitors through. The green was now entirely engulfed.

“These putts will decide the entire Ryder Cup match of 1969,” Henry Longhurst said, setting the stage for his TV audience.

Jacklin was away. He trusted the line more than the length and the putt never made it to the hole, stopping two feet short.

“Anguish Jacklin,” Longhurst said, suffering with him, no doubt, while letting the player tell most of the story, as Jacklin let out a frustrated breath while holding his putter behind his head.

The great Jack Nicklaus now had a putt to win the Ryder Cup. He wasn’t going to leave it short. He didn’t. It raced five feet past.

“Idiot,” he said to himself.

“It was shocking,” Jacklin said. “There was a pregnant silence all around the green.”

So here stood Nicklaus. In his match that morning, he couldn’t make anything from inside this distance. Now he faced what he described as a “downhill left to right slider which is probably the toughest of all putts.” Plus, he said at the time, “I was terrified. I wasn’t putting for me. I was putting for my country.”

But Nicklaus was also the greatest player of his generation, perhaps of all time, and arguably the greatest clutch putter in history. If he ever needed a putt, he’d make it. And he needed this one. To no one’s surprise, but against British hopes, it dropped into the heart of the hole.

He paused momentarily, perhaps thinking about his next move.

Then, before picking his ball out of the hole, he scooped up Jacklin’s coin and handed it to him.

“I don’t believe you would have missed that, but I’d never give you the opportunity,” he told him.

The Ryder Cup was tied for the first time ever in one of the iconic moments in all of sports history. “A gesture that was just unparalleled in our game,” Jacklin called it.

“I don’t know why but I quickly thought about Tony Jacklin and what he had meant to British golf,” Nicklaus explained later. “Here he was The Open champion, he’d been their new hero and all of a sudden, I felt like if he missed this putt, he’d be criticized forever. This all went through my mind in a very, very quick period of time and I just made up my mind. Walk off here, shake hands and have it be a better relationship between two golfing organizations. That would be the right way to do it.”

The two competitors walked off the green arm-in-arm. If Samuel Ryder ever envisioned the perfect personification of his founding ideal, this was it. Nicklaus had tied a pretty bow around a week of animosity and bad blood. The 1969 Ryder Cup is known fondly as The Concession when it could have been remembered as The Contention. Nicklaus had become the game’s greatest sportsman. Nevertheless, while some eventually mellowed, Jack’s captain and teammates were not feeling as benevolent at the time.

Jacklin would likely have made the putt, although some of similar and shorter lengths had been missed during the week. Certainly, it’s more cutthroat at many country clubs’ member-guest tournaments. Understandably, Snead, was incensed, more so behind closed doors than in public. Hell, he would have made Hogan putt it.

“When it happened, all the boys thought it was ridiculous to give him that putt,” Snead said at the time. “We went over there to win, not to be good ol’ boys. I never would have given a putt like that—except maybe to my brother.”

Most of the American players remembered being shocked. As it was happening, Still turned to Beard and asked, “Is he doing what I think what he’s doing?” Years later, Barber told Golf Digest that many felt the grand gesture was driven more out of vengeance toward Snead than magnanimity toward Jacklin.

“You’ve heard how Jack Nicklaus conceded the putt to Tony Jacklin on the last hole on the last day, the competition ending up tied. Jack has said that he conceded the putt purely out of sportsmanship, but I was on the team and none of us players believed that,” Barber claimed. “See, our captain that year was Sam Snead. He sat Jack down in the morning the first day and in the afternoon the second day because he didn’t want Jack to get worn out. Jack wanted to play and was upset about being benched. Most of us believe Jack conceded the putt at least in part to get back at Sam. And it worked, because behind the scenes Sam was furious that Jack didn’t make Jacklin hole that two-footer.”

“I thought a tie was a pretty good result,” Nicklaus said. “My captain didn’t necessarily think so.”

As an aside, Snead’s strategy to keep his Grand Slam winner out of two matches was not as foolish as it appeared. Nicklaus admitted he was never more tired than on the plane ride home after going toe-to-toe with Jacklin for thirty-six holes Sunday.

“That’s when I decided it was time to lose weight. I told Barbara (his wife) to have my clothing altered,” he said. “Four weeks later, I was 180. It may have been the best thing I’ve ever done.”

The slimmed-down Bear finished the year winning the Sahara Invitational and Kaiser International Open Invitational after winning just once prior to the Ryder Cup, then turned it on for the entire decade of the 1970s. It was a personal metamorphosis. Afterwards, the only thing fat about “Fat Jack” was his wallet.

Curiously, while Jacklin was appreciative and the Americans perplexed over the finale, the press hardly noticed the monumental moment. Pat Ward-Thomas wrote the only “game story” which mentioned the concession, and then as a throw-away line in his last paragraph in The Guardian. Max Faulkner, the former Ryder Cupper, wrote of Nicklaus’s “courtesy” in his syndicated column days later and Jack Rowe of the Liverpool Press wondered about the golf shoe being on the other foot.

“(Brown) might have taken the attitude ‘fair enough’ but, somehow, I feel he would have pointed out, no doubt gently, that with the Ryder Cup at stake it would have been better to have kept the pressure on the Americans until the last possible moment,” he supposed.

Most of the scribes—including all of the Americans—wrote that Nicklaus had made his clutch putt. That was that. There were no opinion columns lionizing him for conceding Jacklin’s putt. It took years before it was recognized as perhaps the finest sporting gesture ever made. “The Concession” didn’t enter the sports lexicon until at least the 2000s, shortly before Nicklaus and Jacklin collaborated on a golf course by that name in Florida.

One thing was clear, however. Nicklaus, as perhaps only he could have done, made the match impossible to forget. The editor of Golf Illustrated, Tom Scott, nailed it. “Those who were at Birkdale and saw the final stages of this year’s Ryder Cup match will surely recall it again and again down through the years, for even if they live to be a hundred, I doubt whether ever again they will see a finish charged with so much emotion or filled with such drama.”

While all of Britain rejoiced over the outcome, the result meant that the US retained the trophy, although at the official dinner, in the spirit of Nicklaus’s concession, US PGA president Leo Fraser offered to share it. The Brits could keep it for one year before shipping it back to the States in time for the 1971 matches in St. Louis. At any rate, all of Britain was looking at the tie as a win and celebrated accordingly. The team threw a “moral victory” party after the dinner that night and invited the American team. Only Billy Casper went. According to Neil Sagebiel’s Draw in the Dunes, they were dancing until the wee hours in the halls of the Prince of Wales Hotel.

To America, the tie was like kissing Miller Barber.

The country’s leading sport voice at the time was Los Angeles Times columnist Jim Murray. He used words like Hogan used a 3-iron and wrote a stinging rebuke of the team.

“I have a feeling they are on their way back from Gettysburg,” he began. “Don’t believe the communique that they ‘tied’ Britain, that the battle was indecisive. The 1969 Ryder Cup was a ‘tie’ only if

you consider Caporetto to be one—or Waterloo.

“We were turned back, troops, and it’s getting to be a trend. I’m afraid we’re breeding a generation of hothouse golfers who can play the game only when the fairway is as wide as Rhode Island, the greens are watered, and the rough wouldn’t hide a snake and the nearest trees are two states away.”

Waterloo? The British raised Brown and his boys on a pedestal as they did the triumphant Wellington. Rowe even advocated for making Brown permanent captain. Faulkner wrote that, coming after Jacklin’s Open Championship, they had “beyond question re-established Britain as a leading power,” adding, “the extraordinary thing about it is not that it happened, but the speed at which it happened.”

Like most, The Guardian’s Peter Dobereiner considered the tie a crossroads for British golf. “The benefits arising from the British performance will be considerable,” he wrote. “I doubt whether we shall hear any more talk about expanding the Ryder Cup into an America versus the world to make it a more competitive contest. And from now on young British golfers need not feel any awe for the American super-golfers. In the past—and I suspect, slightly this time as well—the British have gone into the Ryder Cup matches psychologically one down. Next time the matches will at least start all square and then—who knows?”

Dobereiner’s lofty hopes would fall flat. The 1969 Ryder Cup was Great Britain’s last hurrah, even as Nick Faldo, one of those “young British golfers”, supplanted Jacklin as the next English superstar. The Americans won the next four Ryder Cups by comfortable margins of six, ten, five and six points. To Dobereiner’s dismay, the European continent, at Nicklaus’s urging, was appended to Great Britain and Ireland in just ten years’ time.

The Ryder Cup’s best years ensued. For fans of the ancient game, however, 1969 remains a fond memory.