Copyright Bangor Daily News

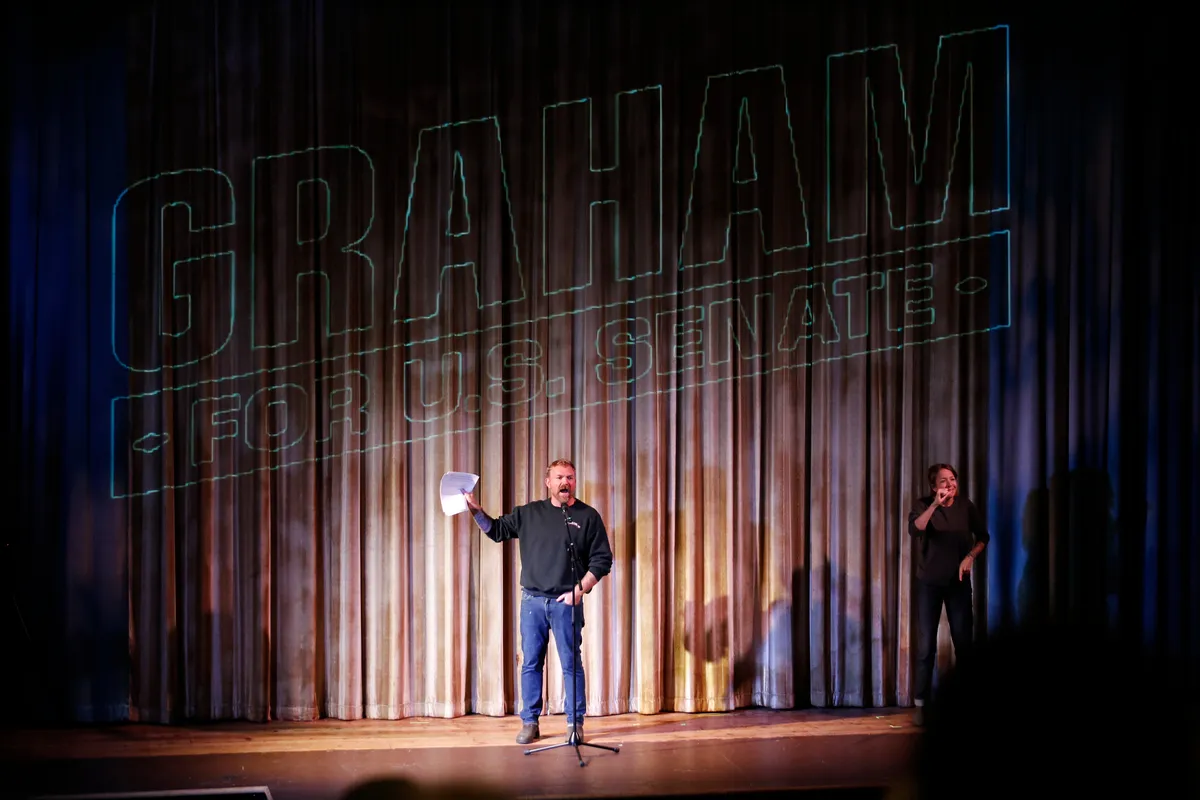

The BDN Opinion section operates independently and does not set news policies or contribute to reporting or editing articles elsewhere in the newspaper or on bangordailynews.com Karyn Sporer is an associate professor of sociology at the University of Maine. These are her views and do not express those of the University of Maine System or the University of Maine. She is a member of the Maine chapter of the Scholars Strategy Network, which brings together scholars across the country to address public challenges and their policy implications. Recent attention has been given to extremism, hate symbols, and a particular veteran running for the U.S. Senate in Maine. Admittedly, I wasn’t surprised to learn that a combat veteran left the military with PTSD and an alleged Nazi symbol tattooed on their chest. While I’ve yet to see concrete evidence that Graham Platner ever ascribed to a far-right ideology, research has shown us for years that radicalization in the military is a serious problem that needs to be addressed. Between 2018 and 2022, the rate of military service in the extremist offender population increased from 11% to 18%. Among those who stormed the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, at least 222 had a U.S. military background. Even the U.S. House Committee on Armed Services recognized “alarming incidents of white supremacy” in the military. And while radicalization in the military should be a major concern, it isn’t the whole story. What we talk about far less is that people also change in the other direction. Individuals who radicalize can, and often do, find their way out. We call this process deradicalization or disengagement, and it deserves as much attention as radicalization itself. Through my work with the National Counterterrorism, Innovation, Technology, and Education Center, a U.S. Department of Homeland Security Center of Excellence, I’ve interviewed family members of individuals who radicalized into different extremist ideologies. While their stories are painful, full of confusion, loss, and fear, they are also filled with unexpected hope. Many watched their loved ones come back, not through punishment or shame, but through patience, empathy, and the slow rebuilding of trust. These experiences reveal something powerful: The same social forces that draw people toward extremism (alienation, identity seeking, unmet emotional needs) can also pull them back when replaced with connection, purpose, and belonging. Those who radicalize are not born extremists; they are shaped by trauma, instability, and broken social bonds (all mentioned by Platner during his public reckoning with past Reddit comments). When extremism enters their lives, whether online, in the military, or through peers, it offers something that has long been missing: belonging and meaning. But just as radicalization happens through social processes, so does deradicalization. People leave extremism when they begin to doubt the ideology or feel emotional costs outweigh rewards. That’s when support becomes critical. Family members often described a turning point, like an illness, a loss, or the exhaustion of living in anger, that opened a small window for reconnection. Change became possible when someone reached through that window with empathy rather than condemnation. Unfortunately, most public conversations about extremism leave no room for this narrative. We talk about radicalization as if it’s a one-way street, as if crossing that line means there’s no way back. That mindset doesn’t just stigmatize people; it undermines prevention. It keeps those who want to leave, or help someone they love leave, from seeking help because they fear being seen as a threat rather than a person in crisis. Deradicalization happens all the time. It happens quietly, outside the spotlight. Organizations like Parents for Peace and Life After Hate provide confidential counseling and support to individuals and families navigating these challenges. Their success stories remind us that recovery is possible, but only if we recognize it as part of the solution. Yes, radicalization is a serious concern, but fear and shame can’t be the only way we talk about it. We also need to ask what happens when someone wants out, when they realize the ideology no longer fits. How do we help them rebuild and be seen as more than their worst mistake? The real challenge is in forgiveness, trust, and reintegration, and even accepting that they might one day run for office.