Copyright gqindia

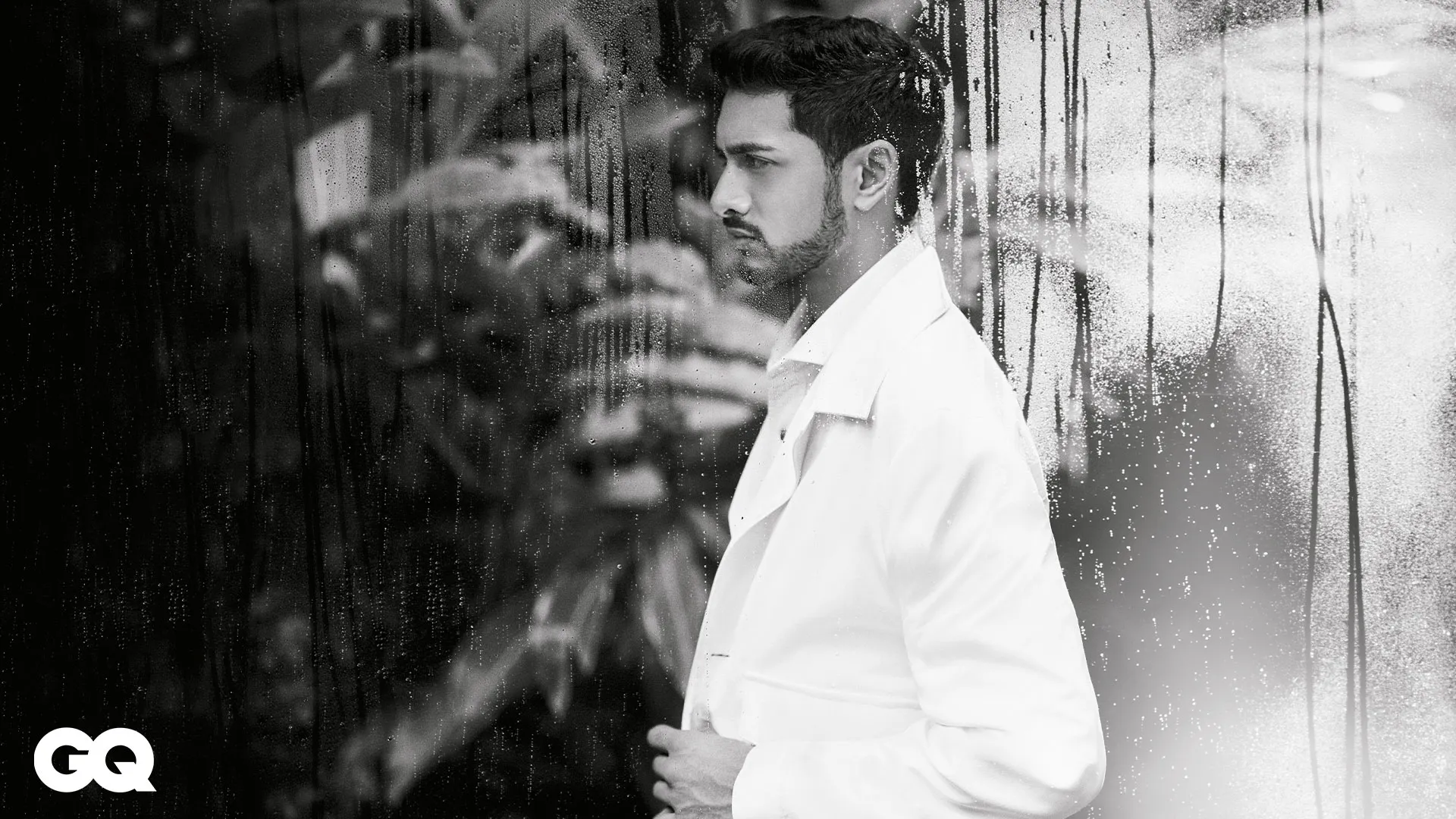

I first met Aryaman Birla, the 28-year-old seventh-generation Birla heir, at a Ralph Lauren Diwali dinner in Mumbai this September. I immediately noticed that he arrived at the venue alone, without any handlers or entourage, and that he did not draw any unnecessary attention to himself through the event. That was unusual, and it struck me as remarkably self-assured. Fresh out of Harvard Business School and having recently been inducted as a director of the $115 billion Aditya Birla Group, the young Birla has been getting his feet wet at the sprawling business empire, which has interests in cement, metals, paints, textiles, financial services, hospitality and a host of other sectors. The group is also a fashion powerhouse, armed with a slew of brands and retail offerings that address the entire cross section of the Indian market, ranging from Sabyasachi, Tarun Tahiliani, Shantnu & Nikhil and Masaba, to scale players like Louis Philippe, Van Heusen, Allen Solly and Peter England, not to mention Pantaloons, The Collective and Tasva, among others. In October, the company opened the ambitious Mumbai outpost of the iconic Parisian department store Galeries Lafayette, which is synonymous with fashion, culture and creativity. Birla is being groomed as a future leader by his father, Kumar Mangalam, who took over as group chairperson 30 years ago—at roughly the same age his son is today. Kumar Mangalam has grown the business 30 times over the years, and like him, his son is looking to help drive long-term, -meaningful economic value, while keeping the storied Birla legacy burning bright. While success is never guaranteed, the tailwinds are in Aryaman’s favour. We met again at the inaugural GQ Heroes summit, where our one-on-one conversation on stage was a hit with the audience, who were struck by Aryaman’s candour, intelligence and authenticity. Rocking a black Sabyasachi jumper, he talks about the pressure of being a -Birla, his thoughts on the business, and his childhood need to carve out a unique identity for himself, distinct from his family name. Edited excerpts: You were a serious cricketer, playing at the Ranji level for Madhya Pradesh. This involved sleeping in dorms, travelling in buses and overnight trains across the hinterland, and a lot of hard work. Why did you put yourself through this when you didn’t need to? When you’re 15 or 16 and come from privilege, you’re often seen as your last name. I wanted to get out of that shadow. There was an innate need to prove to myself, as well as to the outside world, that I could be good at something on my own merit. That I could be Aryaman first, and then Aryaman Birla. And cricket was that for me. It was a profession so far removed from business and anything that my family had done, that there was no way my successes—or failures, for that matter—could have been associated with me being a Birla. Playing the sport competitively helped address the angst within me—to do something for my own name. And it did me a lot of good. My decision to play cricket competitively must have generated a lot of surround sound. But my parents shielded that noise from me, for which I’m grateful. There’s a huge focus in the media on founders and startups. You belong to this multi-generational business family. What kind of pressure do you feel to live up to this legacy that’s so closely associated with success, and how will you confront or deal with failure? There is pressure. That’s the simple -answer… but that’s not nuanced enough. On the one hand, what six generations before me have been able to do is extremely inspiring. When seen from that perspective, without sounding cynical, you don’t want to be the generation that messes it up. But when I look at where our country and the family businesses are placed today, I think I’m extremely privileged to be in a place where I can add a lot of value. This is a platform that not a lot of people have. So I feel a mix of pressure, ambition, excitement and fear. But on a day-to-day basis, I see it as a great responsibility, and it’s something I’m going to try my best to live up to. What was your childhood like? My sisters and I had a normal childhood. We went to school, played sports and participated in many extra-curricular activities. We had friends, and our lives didn’t seem any different from theirs... Now that I think about it, in the background, obviously, we knew there was a certain responsibility, a certain name that we came from. Maybe subliminally, I knew of it, but I didn’t think of it actively as a kid. And that’s because our parents never let it come to the fore. When did you know that you belonged to a famous family? It’s hard to pinpoint a specific time. When I was a kid, I was almost embarrassed by my last name. When you’re in the third grade and someone asks you, “How many cars do you have… I’ve heard you have lots of cars,” it jars you a little… I was just a kid. Episodes like this made me shy away from my name. When I used to go to the maidan to play cricket, I used to tell the driver to drop me 500 metres away from the ground, so that no one would see I was being dropped off in a car. But then, as I played cricket more seriously, left the south Bombay bubble and went deeper into India, I realised the way people saw me and reacted to my last name was very different from what I was used to. There’s so much respect associated with being a Birla. For example, someone once told me their parents caught them sitting around watching TV and asked them, “What do you think, you’re from the Tata or Birla family?” That statement really struck me. And I realised it was a deep-rooted feeling in our country, something to be extremely proud of. So over time, the embarrassment changed to comfort and then pride. It’s been a journey to get here. GD Birla was a close ally of Mahatma Gandhi, and your family played a vital role in the freedom struggle. What, according to you, are the Birlas’ major achievements? I’m extremely proud of what my family has done, and yet I feel a little embarrassed to speak about it. The fact that the family has been so intertwined with both the societal and economic development of the country—pre-Independence, at Independence and post-Independence—I’m just extremely grateful, and hopefully I’ll be able to carry this legacy forward in a manner that does it justice. Your company has more than 2.2 lakh employees, of all ages and backgrounds. Some are in their 70s, while many are in their early 20s, and most, in between. How will you navigate and define the company culture for this multi-generational workforce? I want to be seen as someone who’s accessible. Large businesses in India that have been around for a long time have generally been seen as hierarchical in nature. And while I’m not trying to come in and disrupt that on day one—that’s just not how I would work—I’d like to break that culture down a little bit by being someone who enables decisions, as well as people, to voice their opinions without fear. I think this is a journey that will take some time, but I hope I can be approachable and relatable, and be seen as someone who is ambitious and aggressive but also empathetic to people and their needs. What’s one important lesson you gained at the Harvard Business School? The greatest lesson is that no one really knows what they’re doing. And that’s extremely powerful. Harvard’s pedagogical approach involves going through 600-700 case studies of real-life companies and the issues they’ve faced over time. You would think that one would come out with very concrete answers at the end of each case. Yet, for most cases, the answer to any question is, “It depends”. So you learn that there’s no absolute right or wrong answer, but you have to have conviction in what you do. Sometimes you will get it right, and sometimes you will get it wrong. And that’s an extremely important tool and lesson. Head of Editorial Content: Che Kurrien Hair: Suhas Mohite Make-up: Ridhi Matreja Art Director: Mihir Shah Entertainment Director: Megha Mehta Senior Entertainment Editor: Rebecca Gonsalves Visuals Editor: Shubhra Shukla Fashion Assistant: Nandini Jain