By Anna Merlan,Stephanie Mencimer

Copyright motherjones

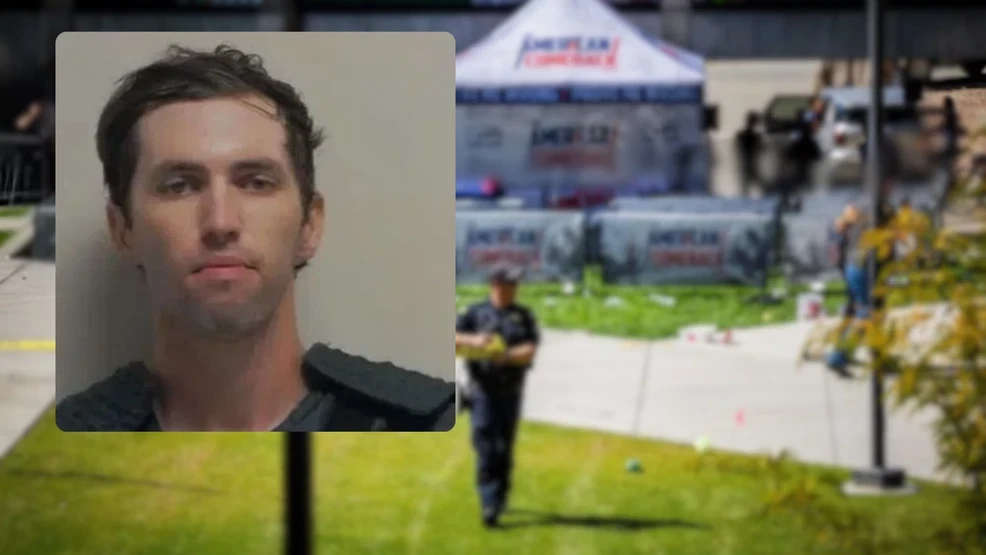

Since the murder of MAGA influencer Charlie Kirk last week in Utah, the state’s Republican governor, Spencer Cox, has won plaudits for his general moderation. In his press conferences and TV appearances, he was perhaps the lone member of his party to remind Americans that the person most responsible for killing Kirk was the young man who shot him.

“We can return violence with violence. We can return hate with hate, and that’s the problem with political violence—is it metastasizes,” he said in a Friday press conference after Kirk’s alleged shooter was apprehended. “Because we can always point the finger at the other side. And at some point, we have to find an off-ramp, or it’s going to get much, much worse.”

Stepping into the role of national mediator has been a natural fit for Cox. He has spent the past couple of years trying to get Americans to find common ground through his “Disagree Better” initiative at the National Governors’ Association. He toured the country touting volunteering as an antidote to our social and political polarization while promoting conflict resolution tools for people to use around the dinner table and in political conversations. And he helped organize events with ideological opposites like Supreme Court justices Sonia Sotomayor and Amy Coney Barrett to model respectful disagreement as a defense against political violence.

Cox sees in the aftermath of the Kirk shooting a chance for his Mormon-dominated state to lead the country away from the brink. “Maybe, just maybe, there’s a path forward for our country that comes through the great people of Utah,” he told the Atlantic’s McKay Coppins over the weekend.

Showing the country how to pull back from the brink, however, will require more concrete action than just calling on people to put down their phones and “touch grass,” as he said on Friday. “Interventions to reduce affective polarization will be ineffective if they operate only at the individual, emotional level,” wrote Rachel Kleinfeld, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, in a September 2023 essay reviewing the existing studies on the subject. She explains that the country’s current divisions often stem less from individual polarization than from structural issues and “partisan incentive structures to win at all costs in order to win ultimate power.”

“Political violence is not random,” Barbara Walter, international affairs professor at UC San Diego and the author of How Civil Wars Start and How to Stop Them, told Politico recently. “Research shows it becomes far more likely under four conditions: when democracy is declining rapidly, when societies are divided by race, religion or ethnicity, when political leaders tolerate or encourage violence, and when citizens have easy access to guns.”

Like much of the country, Utah, with an increasingly diverse population and its famously lax gun laws, checks all of those boxes. And while Cox neither tolerates nor encourages violence, he has helped undermine democracy through one of the state’s most divisive political controversies: partisan gerrymandering.

Starting with Texas, Republicans across the country have recently launched an arms race of mid-cycle partisan redistricting to respond to President Donald Trump’s request to further suppress Democratic representation in Congress. Utah, however, doesn’t need to take such drastic measures because Republicans have already spent 25 years crushing the ability of Democrats and independents to have a meaningful voice in state politics.

Former state Rep. Jim Dabakis, who was chair of the Utah Democratic Party during the 2011 redistricting, once described it as “the American political process at its ugliest, meanest, and most selfish, where legislators are picking their voters, instead of having the voters pick the legislators.”

Republicans make up about half of all 2 million registered voters in Utah. The last time the state elected a Democratic governor was in 1980. But nearly 600,000 voters aren’t affiliated with either party. Many of them vote like the state’s 280,000 registered Democrats. In 2024, while only about 15 percent of voters were registered as Democrats, nearly 40 percent of statewide voters pulled the lever for Kamala Harris for president. Most of those liberals are concentrated in Salt Lake County, where Harris actually beat Trump, winning 53 percent of the vote.

Yet those numbers aren’t reflected in the state’s congressional representation, which is solidly Republican (and male). The state legislature draws electoral boundaries and, for more than two decades, Republicans have maintained a veto-proof supermajority. The legislature is 80 percent Republican and 98 percent white in a state that’s now nearly 17 percent Hispanic. Nine out of every ten seats are also held by Mormons, even though only 60 percent of Utah residents today are LDS.

Cox served briefly in the state legislature before being appointed lieutenant governor in 2013, and then elected governor in 2020. He seems to understand why people in his state are unhappy about gerrymandering. “There is nothing in the history of our country that makes people angrier and makes them lose trust than when they feel like the government is not being responsive to them,” he said at an event recently. That doesn’t mean he’s done anything to change the situation. In fact, he’s supported it.

The case of Rep. Jim Matheson is instructive. Back in 2000, he was Utah’s sole Democrat in Congress, and his district consisted entirely of Salt Lake County. But the following year, Republicans who couldn’t beat him at the ballot box tried to get rid of him by redrawing his district. The new district’s configuration predicted that a generic Republican should be able to win it by at least 15 points. But Matheson was a Blue Dog and the popular son of the state’s last Democratic governor, Scott Matheson. He continued to get reelected.

Because of its rapid population growth, Utah earned a fourth congressional seat after the 2010 census. So, in 2011, the legislature once again tried to redistrict Matheson out of office, this time changing his district boundaries to cover even less of Salt Lake County and more rural areas. In 2012, Matheson switched to the new district, which was heavily Republican but covered more of Salt Lake City. He narrowly won that race, too.

Matheson retired in 2014, and the seat passed to the late Republican Mia Love. But the district proved remarkably competitive, and in 2018, Democrat Ben McAdams bumped off Love. He was defeated in 2020 by the current office holder, former NFL player Burgess Owens.

After all these GOP efforts to consolidate their power, many Utah voters were fed up. In 2018, they narrowly passed a ballot initiative that banned partisan gerrymandering and created an independent redistricting commission charged with drawing up nonpartisan election districts. The state legislature, however, quickly repealed the new law in 2020. The following year, after only 90 minutes of floor debate, they passed an egregious new congressional map that cracked the Salt Lake area into four districts, ensuring that Democratic voters didn’t make up more than about 22 percent of any of them.

By this time, Cox was governor, and state residents protested at the Capitol and called on him to veto the map. He approved it anyway, arguing that the legislature would simply overrule him if he did otherwise. “I’m a very practical person. I’m not a bomb-thrower, and I believe in good governance,” he said at the time. “I’ve been told that a veto just for the sake of a veto is something that I should do. I just think that that’s a mistake.”

Cox’s failure to defy his party for the sake of democracy is one reason why many state voters saw his “Disagree Better” campaign as disingenuous at best. After all, it’s hard to disagree better when you’re not even allowed a seat at the table.

But that could soon change.

Good government groups who’d help pass the 2018 ballot initiative sued over the new maps in 2022, arguing that the legislature had violated Utahns’ rights to participate in free elections. The state legislature asked the Utah Supreme Court to block the lawsuit. Cox filed an amicus brief supporting the GOP-led legislature. In 2024, the court ruled that the legislature had overstepped its authority in thwarting the will of the people expressed in the 2018 ballot initiative and allowed the case to move forward.

On August 25, 2025, 3rd District Judge Dianna Gibson, who was appointed by Cox’s predecessor, Republican Gary Herbert, threw out partisan redistricting maps and ordered legislators to come up with fair, nonpartisan redistricting in keeping with the 2018 ballot initiative. The legislators have until September 25 to comply so that fair maps are in place for the 2026 midterm elections.

After Gibson issued her August order, furious Republican legislators began looking for any way to avoid following the order, up to and including threats to remove Gibson from the bench. Even Trump weighed in on the decision.

“Monday’s Court Order in Utah is absolutely Unconstitutional,” he wrote on Truth Social. “How did such a wonderful Republican State like Utah, which I won in every Election, end up with so many Radical Left Judges? All Citizens of Utah should be outraged at their activist Judiciary, which wants to take away our Congressional advantage, and will do everything possible to do so. This incredible State sent four great Republicans to Congress, and we want to keep it that way. The Utah GOP has to STAY UNITED, and make sure their four terrific Republican Congressmen stay right where they are!”

Cox also opposed the judge’s decision to throw out the partisan maps, suggesting that it was now Democrats who wanted to win an unfair advantage. “Democrats in our state desperately want a district, even though Republicans outnumber them three to one in the state,” he said. “The only way to get a Democratic district in the state is to gerrymander.”

In fact, nonpartisan maps proposed by an independent commission would give Democrats a much better shot at winning a single congressional seat, but mostly the new maps would make all the districts more competitive, which democracy advocates say is the preferred way to force partisans to compromise for the public good.

Late Monday, the Utah Supreme Court ruled against the legislators and upheld Gibson’s order, raising the possibility that after the long fight for better democracy, Utah voters might prevail. Elizabeth Rasmussen, executive director of Better Boundaries, one of the groups that helped pass the ballot initiative, thinks it’s possible. “Utah is a special place,” she told me. “I am optimistic that the legislature and governor will show the country that the ‘Utah way’ still exists in such a polarized world by finally enacting the fair maps that Utahns voted for.”

Given its history, though, the state GOP is clearly not going to give up without a fight. Like many places, Utah has a vocal minority of GOP extremists and conflict entrepreneurs who have steadily been pushing the state to the right. They have been a persistent problem for more moderate Republicans like Cox.

When he appeared at Utah’s GOP nominating convention in the spring of 2024, Cox was booed by the state’s radical, MAGA diehards who made up most of the delegates. He lost the vote to Phil Lyman, a Republican state representative who was pardoned by former President Donald Trump for a trespassing charge he picked up for driving an ATV in an illegal protest on public lands in 2014. Cox had to get on the ballot through statewide signature collections the same way Mitt Romney did in 2018.

He was reelected last year with only 53 percent of the statewide vote, underperforming Trump by 7 points. Going so far as to buck his own party to support fair redistricting may be even more fraught for Cox than pushing back on the president, which he has also refused to do.

Yet, in a sign of the volatility of the current situation, even Cox’s mild calls for calm over the past week have been met with outrage from the far right nationally. “Cox represents the dead Republican Party that is just too gutless to engage here and wants to look the other way,” MAGA luminary Steve Bannon fumed on his War Room podcast Monday. He accused Cox of upstaging FBI director Kash Patel and harboring too much sympathy for LGBTQ people. “Cox is part of the problem.”

Facing down such criticism isn’t for the faint of heart. But conflict researchers say such leadership is critical to de-escalating a highly polarized situation, and that even changing the language of the debate, as Cox seems to be trying to do, is an important step.

Robert Pape is director of the Chicago Project on Security and Threats (CPOST) at the University of Chicago. “Political violence is like a wildfire,” he told me last year. “You need both combustible mass material—dry wood—and you also need a trigger, like a lightning strike or a cigar butt.” The Kirk murder certainly qualifies as a trigger. But Pape said violence isn’t inevitable. The outcome depends heavily on what political leaders do. “Leaders can act either as a trigger or a damper.”