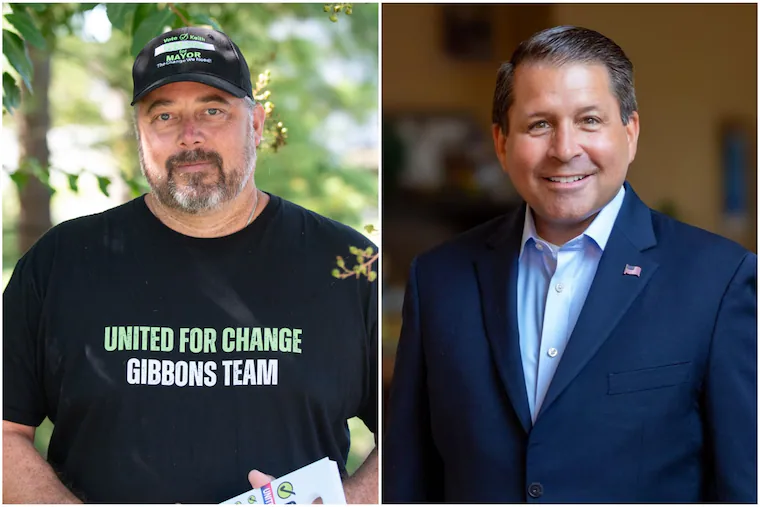

A battle over the proposed sale of Gloucester Township’s sewer system is back on the ballot as key players face off in the mayoral race.

After spearheading a campaign last year that overwhelmingly blocked the sale of the Camden County town’s sewer system to a private water company, Keith Gibbons is drawing on his local renown to run for mayor.

The race is between Gibbons, a self-employed independent who has served on the Gloucester Township School Board for three years, and 15-year incumbent Democratic Mayor David Mayer, an executive at New Jersey American Water, the company that unsuccessfully sought the township’s sewer system. Both sides are hurling insults and accusations.

Gibbons is a “con artist,” Mayer’s campaign asserts, adding that Mayer recused himself from any township business related to the sewer sale to dispel the appearance of a conflict of interest.

Some of Mayer’s supporters say without evidence that Gibbons is backed by extremists who want to defund police, a claim Gibbons refutes.

Gibbons, meanwhile, has criticized Mayer for being part of the “South Jersey Democratic political machine that runs this town.”

» READ MORE: A pending $143 million sewer sale in South Jersey has ignited a battle of lawn signs and campaign ads ahead of Election Day

Last year’s sewer fight was so consequential, it’s still reverberating this election. Residents supporting Gibbons believe that although they won the referendum, there’s a chance township officials will again try to sell the sewer system if Mayer wins reelection.

Both sides are politicking with fervor, denouncing each other in the continuation of a fight fueled by an enmity that hasn’t stopped flowing since last year.

‘Shocking overreach’

The conflict began in 2023 when the Municipal Utility Authority, which ran the sewer system autonomously, voted to dissolve itself. That gave the township council control over the system.

The decision alarmed many of Gloucester’s 66,000 residents who feared the public system would be sold to a private company that would charge more.

During sworn oral testimony in a May 2023 teleconference, Mayer and an attorney representing the township were asked whether the utility would be sold within the following five years, according to a transcript of a meeting of the New Jersey Department of Community Affairs Local Finance Board, which oversees fiscal operations of local governments.

“There is no current expectation to sell either portion [water or sewer] of the system,” the attorney said. Mayer agreed.

“Eleven months later, they were putting out bids for selling the sewer system,” said Peggy Gallos, executive director of the Association of Environmental Authorities, a New Jersey trade association of governmental entities in charge of sewage, water, and solid waste.

In July 2024, the township received two widely contrasting bids: one from Aqua for $52 million and another from New Jersey American Water for $143 million, with a promise to spend an additional $90 million in capital improvements of the sewer system.

The township went with the larger bid from Mayer’s company, citing debts that had to be paid.

“The overreach of the winning bid was shocking,” Gallos said. “They promised to do more work than necessary — the system needed around $25 million in improvements, not $90 million. That’s how private companies make a profit.”

A New Jersey American Water spokesperson didn’t address Gallos’ assertions. Instead, she said the company is committed to making improvements, adding that throughout the company’s service area, average water and wastewater bills “remain below 1-2% of median household income.”

Asked more than a dozen questions about the sale and the mayoral race, the mayor’s office didn’t respond. Denise Lugo, Mayer’s campaign manager, emailed anti-Gibbons campaign material.

Grassroots campaign

Gibbons, 48, has had a varied career, from running a Christmas tree farm in Oregon to working for Live Nation in Philadelphia.

He moved to Gloucester Township in 2006, and by 2024, when the township council announced a referendum on the sewer sale would be on the November ballot, Gibbons threw himself into the fight.

He led a grassroots campaign that included a podcast and door-to-door canvassing with activists.

New Jersey American Water launched its own $800,000 campaign.

Gibbons said township residents were concerned the mayor had a conflict of interest as the water company’s director of government affairs.

New Jersey American Water said attorneys helped Mayer recuse himself by “establishing firewalls” around sewer discussions.

Gibbons’ efforts helped convince more than 80% of nearly 28,000 voters to defeat the referendum.

Now, running for mayor as an independent, he’s getting support from Republicans in a township where Democrats hold a 2-to-1 registration advantage.

“We didn’t want to have a third party drawing votes from Keith,” said Tom Crone, Gloucester Township’s Republican Club chairman. “We liked what he did with the sewer.”

That left a hole in the Republican slot. Soon a “shadowy figure” appeared, Crone said — an alleged “phantom” candidate named Neil Smith who announced he was running as a Republican.

“He had no voting record and didn’t move in Republican circles,” said Crone, who contended Smith was recruited by Democrats to draw away Gibbons’ votes. Calls to the Camden County Democratic Committee were not returned.

Trading accusations

A PAC known as Gloucester Township Citizens for Government Reform is sending out numerous fliers accusing Gibbons, without evidence, of accepting support from extremists wanting to defund police.

However, as a member of the local school board, Gibbons has voted for funding to pay for extra police protection in school.

The Mayer campaign wrote in an email that Gibbons is supported by a “radical left-wing” candidate who wants to defund police.

Gibbons said his opponent’s campaign is referring to Kate Delany, head of the South Jersey Progressive Democrats, a grassroots organization. There’s no evidence that either Delany or Gibbons has ever advocated defunding police.

Mayer’s side charges Gibbons is under investigation by two state commissions.

Regarding alleged investigations, The Inquirer confirmed the New Jersey Election Law Enforcement Commission (NJELEC) received a complaint that Gibbons misused funds by transferring around $3,000 collected for his anti-sewer sale fight into his mayoral campaign.

According to the NJELEC Compliance Manual for Political Committees, such a transfer isn’t improper because political committees can make contributions to candidates. A state government official who didn’t have permission to speak on the record said Gibbons did nothing wrong.

Mayer’s campaign also said Gibbons was the subject of an investigation by the state School Ethics Commission, which neither confirmed nor denied the claim.

Mayer’s representatives touted the incumbent’s record, pointing to achievements such as implementing “innovative” policing strategies, introducing a solar discount program to lower electric bills, and preserving more than 1,000 acres of land.

As the race continues, Gibbons, who promises to be “more transparent and responsive” than Mayer, knows he faces an uphill battle as an independent candidate without the support of a political party.

“It was never my intention to run,” Gibbons said. “But the referendum went well, and it’s hard not to speak out. And they could try to sell the sewer system again.”