By Albert Bakhtizin

Copyright scmp

In recent years, the world has seen a growing wave of confrontation, primarily in the realms of trade, finance and information. At the same time, current trends across most nations point towards declining fertility, population ageing, shrinking labour forces and the intensification and reconfiguration of global migration flows.

What will China, a demographic giant today, look like over the course of this century? What kind of social profile will this country have by the end of it?

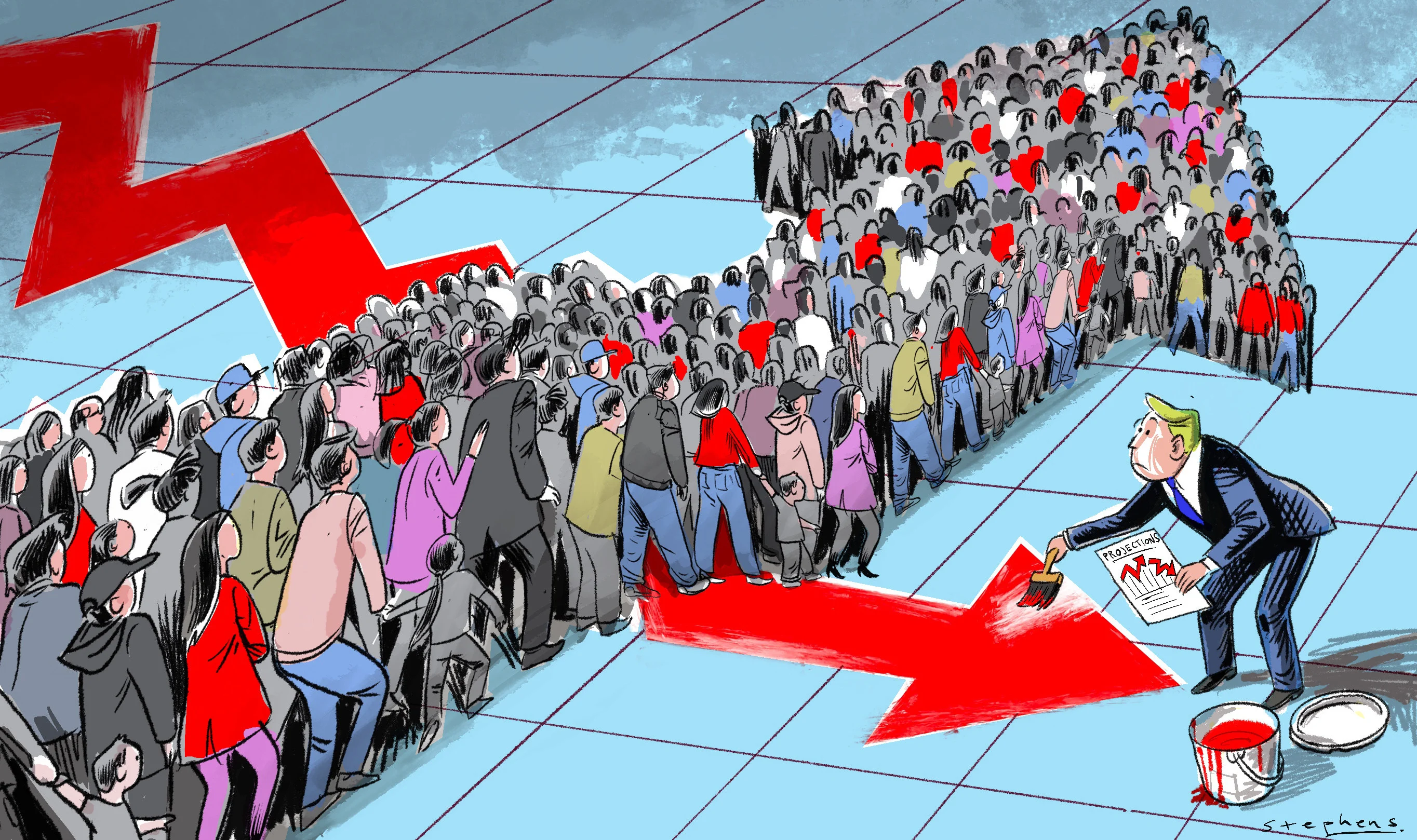

To begin, let us turn our attention to the projections from the most widely cited organisation in the field of demography, the Population Division of the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs. According to its baseline forecast, China’s population is expected to decline by a factor of 2.2 by the end of the century, reaching 633 million. However, the more critical issue lies elsewhere.

China is also projected to become a global leader, so to speak, in terms of population ageing, with people aged 65 and older making up nearly half of the total population by 2100. This would turn up the pressure on the pension system and slow down economic growth.

It is highly questionable whether such a drastic projected decline in China’s population can be taken at face value. If we examine the projections, we find that Russia’s population is also projected to fall by 15 per cent to 126 million by the end of the century, while the population of the United States is expected to grow to more than 420 million over the same period. No clear justification is provided for the declines in China and Russia versus the increase in the US.

However, other data tells a different story. If we look at the forecasts produced by researchers from Renmin University of China and Peking University, China’s population by the end of this century is expected to range up to around 1.12 billion in a moderate scenario.

In 2023, my institute, together with colleagues from the National Supercomputing Centre of China and the IT company Milestone Software of Guangzhou, also conducted population projections through to the year 2100 for all 193 UN member states. According to our baseline scenario, China’s population will reach 1.0287 billion.

As we can see, these are entirely different figures from those published by the United Nations and then widely circulated by global media outlets, which may distort international investment decisions.

Let us move on to what we might call “scare narrative No 2”, the topic of population ageing. This theme is widely discussed in media reports and, according to many experts, it is expected to suppress economic growth.

Let us begin with a counterexample from the IMF, which published a special report titled “Sustaining Growth in an Ageing World”. The study argues that ageing does not necessarily lead to slower economic growth. According to International Monetary Fund estimates, improvements in health and cognitive abilities among older adults can boost their participation in the economy and contribute an additional 0.4 percentage point to economic growth annually from 2025 to 2050.

Our own calculations also show that investments in human capital such as extending active longevity, improving healthcare and education, and involving older people in the economy always pay off in the long term. In other words, a sound government strategy for adapting to population ageing can turn this challenge into a driver of growth.

Should international migration be viewed as a reliable way to compensate for population decline? Until recently, many analytical institutions, including the IMF, assessed its impact on the economy as overwhelmingly positive. However, an increasing number of studies explicitly state that not all migrants are equal.

According to some estimates, low-skilled migrants impose fiscal costs, while high-skilled professionals generate net gains. Meanwhile, factors that reduce dependency on migration include the automation of production and the rapid adoption of artificial intelligence technologies.

Still, beyond maintaining the existing population, it is essential to stimulate birth rates through both direct and indirect measures. In recent years, China has experienced accelerated urbanisation. The populations of its largest cities have grown significantly. For example, Beijing’s population increased from 13.569 million (1.09 per cent of the national population) in 2000 to 21.893 million (1.55 per cent) today.

If we plot century-long data series for birth rates (which trend downwards) and the urban population share (which rises), we end up with dynamics that can wipe out entire nations. In other words, we must create conditions for balanced settlement instead of encouraging population concentration in megacities and, soon, gigacities.

Of course, from the standpoint of service provision, it is economically efficient to concentrate people in limited areas. However, human beings do not reproduce inside high-rise cages. What we need is a new type of urbanisation strategy similar to what was adopted in the United States in the mid-20th century, with a focus on developing suburban areas. That example proved remarkably effective. Between 1939 and 1958, the US total fertility rate rose from 2.17 to 3.75.

Our joint calculations with Chinese colleagues show that with a well-designed strategy of de-urbanisation, involving the development of areas beyond megacities, the creation of attractive green zones, more living space and high-quality infrastructure, it is possible to maintain the populations of both China and Russia close to their current levels by the end of the century.

China and Russia have the potential to become global leaders in rethinking the most critical demographic challenges. These challenges will shape the trajectory of the 21st century.