By David Thomas

Copyright african

I expected a wall of protocol policed by bodyguards on this hot summer afternoon – instead the welcome was as cool as a West African breeze off the Cape Coast. I was picking my way on foot through the grand terraces of Belgravia, in London, in search of the former head of state of Ghana; I decided to ask directions from a young man cleaning a black Land Rover Discovery.

“Who are you looking for?” he asked.

“Former President John Kufuor,” to which the driver jerked his head to the left, indicating I should follow him inside.

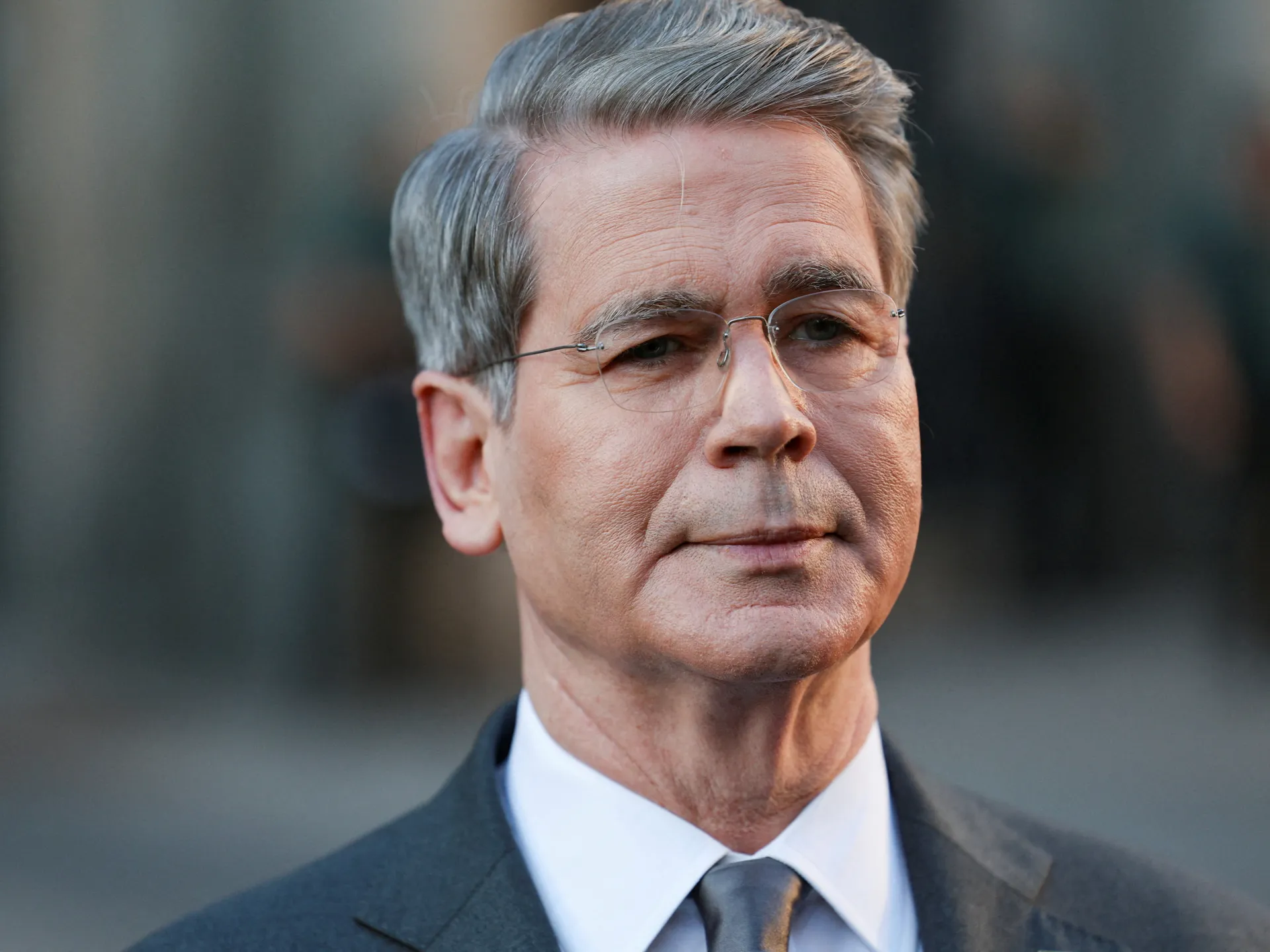

Twenty seconds later, Kufuor and I were face-to-face for the first time in 27 years. The bespectacled Kufuor, smiling, appeared every inch his nickname the “gentle giant”.

He was dressed in a blue-and-white patterned suit with a Chinese collar topped off by a bouquet of dark blue handkerchiefs in the top left-hand pocket.

I joke about the last time I interviewed him, a lifetime ago, when he was in opposition, in a hotel in Gaborone, Botswana, in 1998. I was covering a conference for African opposition leaders for TV.

There had been days of rancour, decrying how ruling parties were grinding down the opposition from Cape Coast to Cape Town.

In what I recall as, understandably, a fairly sour and angry conference, Kufuor was one of the most cheerful and affable delegates. I spotted him walking across the hotel car park, on his way to pack for the airport, and asked for an interview.

We set up the camera in his cramped hotel room; it was tough as there was hardly space for the single bed. I asked him for a few words so we could set the recording levels.

‘I am going to be the next president!’

“My name’s John Kufuor and I am going to be the next president of Ghana!”

The cameraman and I locked wide, surprised, eyes. At that time Kufuor wasn’t seen by many as a guaranteed future president, given his defeat to Ghana’s flamboyant former military leader Flight Lieutenant Jerry Rawlings in 1996.

His supporters, however, did. In 2000 he became the tenth president of Ghana, defeating John Atta Mills, Rawlings’ VP, in a tight contest that marked the country’s first democratic transfer of power. He served two terms in office until 2009.

“You see, even back then, I knew!” he says with a deep hearty laugh as we reminisce.

“The atmosphere was good. The good thing is: my government didn’t arrest anybody without the due process of the law. We were determined to respect the constitution,” he says.

“The first law my government repealed was the criminal libel law, which had been imposed by the British colonial system to make sure media people didn’t talk too loosely against them. I said let’s help the media keep those in power on their toes.”

The economy was a tougher nut to crack.

“I think we did our best. We wanted development, but the economy was in a shambles. We had to take the Highly Indebted Poor Countries initiative with the IMF, to free Ghana from the debt. Ghana was insolvent in 2000 and 2001. We were trying to work within the conditionalities. There was excessive borrowing. Over $4bn in debt was cancelled. Subsequently we got benefits of about $8bn dollars for Ghana. That gave a good image of our government to the world, so that attracted investors and oil companies; Tullow, from Britain, came. They all started coming to Ghana; banks started coming.”

There was also a stint as chairman of the African Union in 2007 to 2008, before leaving the Ghanaian presidency in early 2009 with good grace.

A new challenge

At the age of 86, Kufuor is far from retired. He is looking ahead to the kind of project that fills most business-types with dread these days – a pan-African news channel.

On the one hand a continent-wide network powered by Africans telling Africa’s story is fashionable and laudable; Kufuor advocated for it, at presidential level, with the African Union.

On the other, it has cost many a hard-headed entrepreneur millions of dollars in a business that needs deep pockets.

“All the countries have been insisting on sovereignty, being exclusive, but our mission is to make Africa more direct and connect with people, to tell the world what Africa is and what Africa is trying to do… You have to believe in the position of Africa telling its joy to the world and thereby attracting the partners that Africa needs.”

Kufuor envisages the news service being distributed through an app and has been talking to Afreximbank and the African Development Bank about investment, as well as universities and the private sector.

How will it turn a profit? “Everyone is tapped into their mobile – there could be billions in this one,” he says.

He adds that a lot of media outfits on the continent are in thrall to governments and believes a pan-African news channel can tell the stories that matter.

“If people could identify the app and subscribe to it, it should be able to generate the resources to allow the journalists to do their work without being at the beck and call of a master, or a politician, whose ambitions may not tally with what Africa needs,” he says.

The name of Kufuor’s dream could need a bit of work if it is to catch the imagination. “The Africa Public Interest Media Initiative. We may change to the African Broadcasting Network, depending on the partnership,” he says

A gilded youth

It is a grand idea from an African statesman who lived a golden youth; a meteoric rise driven by academic success that warmed his cold and hungry student flat in London’s Muswell Hill.

John Agyekum Kufuor was born in Kumasi in central Ghana on 8 December 1938. He was the seventh of ten children of Nana Kwadwo Agyekum, an Asante royal, and Nana Ama Dapaah. He was always a young man in a hurry.

The young Kufuor was top of his class at Prempeh College in Kumasi – a school modelled on Eton – before travelling to study law in London at the end of the 1950s. He enrolled at Lincoln’s Inn, London, one of the four famous Inns of Court and more than 700 years old. He was called to the Bar in 1961, aged 22.

“It was something. That time when you walked along Chancery Lane, in London, you saw barristers with hoods, gowns and wigs. These days you don’t see those things,” he says.

He entered Oxford University in 1964, and passed his BA Honours degree in philosophy, politics and economics – “PPE”, a degree for those wanting to lead in public service. He was subsequently conferred, in accord with Oxford traditions, with a Master’s degree by the University.

“I lived in Exeter College; it didn’t have central heating. I was privileged in college; I had a bedroom and sitting room. I remember the winter of 1961 to 1962. All I had, as a poor boy from Africa, to warm me through the winter was blankets and pillows. Later, I lived in a cold flat in Muswell Hill in London and all I had to warm me was a paraffin heater.”

But this set Kufuor up for a meteoric rise. By his mid twenties he was back home in Kumasi practising as a lawyer. He recalls his first ever case, which he won.

“Just outside Kumasi, a criminal case involving a motor, in which a mother had been negligent to leave her little son by the roadside and a lorry ran over him. I got the lorry driver acquitted,” he says.

By the age of 27 he was town clerk, running Kumasi and its 4,000 employees. By the age of 30 he was an MP.

Looking back on his time studying in the UK, the young man was impressed.

“We had been independent just two years… comparatively it looked like Europe was so far ahead of Africa.”

Backing the youth of Africa

No more, he says. The youth of Africa, especially his young compatriots from Ghana, are forging ahead honing their skills around the world. “There is so much mobility through technology. You go to China, you see Ghanaians everywhere… Go to India, the US. Singapore, everywhere. I had the opportunity to go to Iceland six years ago and I saw 19 Ghanaians working there, I couldn’t believe my eyes!”

This is one reason why Kufuor pours time and money into his mentorship programme based on leadership, for which the University of Ghana has given land for a permanent home. In the last seven years, it has produced 200 students. Kufuor calls them: “the pilgrims”.

“We have one or two from outside Ghana. All 30 are picked on merit, online – not ‘who you know’. In the last selection of the 30, 21 were women – they are outperforming the boys now!” he says.

“They are doing so well. One works in the British parliament. Another is an Oxford postgraduate who was picked by TikTok when it set up in Dublin. Another is in Georgetown University.”

‘Power can be so intoxicating’

What about the present crop of African long-term leaders overstaying their welcome?, I ask.

“Power can be so intoxicating; you get it and you become the font of all… Sooner or later you begin to believe that you are specially made in heaven. Recognition of the human individual, in terms of fundamental human rights, will be the order of the day in the future.”

Looking to the future, Kufuor has hopes for the economic prospects of his country, which he believes will be stimulated by more intra-African trade. “We have to move, because we hardly trade among ourselves; we are still in the pigeonholes colonialism put us into. We need powerful advocacy. When people from the grassroots get to feel it [trade’s impact], this is what we need for us to be taken seriously among ourselves. Soon, the continent will have the population of over two billion – bigger than China!” he says.

“People ask: why can’t a businessman from Ghana move to Nigeria, which is only 300 miles or so away, and trade legitimately and fairly? If you want to move a big articulated truck from Accra to Nigeria you would be lucky to do it in more than two or three days, there are so many borders to cross. If the borders are liberalised, then trade will come.”

It has been more than an hour of chat with Kufuor, and he has to leave to attend the graduation of his great-granddaughter, at a nearby London university. It is sure to bring back memories of Kufuor’s own youth amid Britain’s academic elite – and stands as a reminder of how much can be still achieved with a head full of dreams long after that youth has passed.