When Genghis Khan died in 1227, he left behind a united Mongolia, a vast empire, and an unsolved mystery—his final resting place. He took the location of his burial site to the grave, ensuring that his remains would be laid to rest where they would never be disturbed.

Despite the secrecy some scholars still hope to find Genghis Khan’s burial site, which would allow them to put a final bookend on the life of one of history’s most significant, and controversial, figures. Though some people remember him as the founding father of Mongolia, others depict him as a fearsome conqueror who built an empire by blood and iron.

If Genghis Khan’s burial site still exists, many experts believe it lies on holy ground atop a remote, inaccessible mountain that is protected by custom and law. Some, like National Geographic Explorer Albert Lin, have leveraged cutting-edge technology to search for the burial site in innovative, non-invasive ways. Still, other scholars believe the search for the grave is both futile and out of step with Genghis Khan’s wishes.

What have researchers learned about Genghis Khan’s tomb—and will we ever pinpoint its exact location?

Who was Genghis Khan?

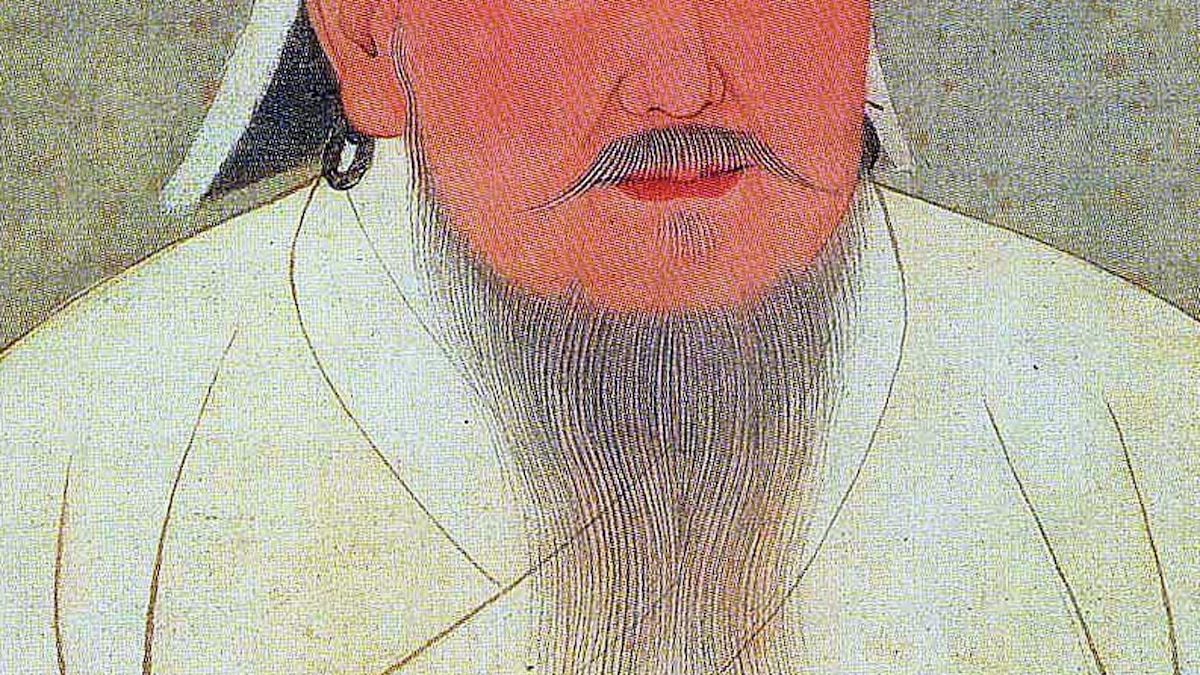

Before he was Genghis Khan, he was Temüjin, a member of a Borgijin clan who was born sometime around 1160.

At the time, Mongolia was divided amongst nomadic clans who frequently warred and vied for power. His father, Yesugei, was a warrior whose military prowess won him status and renown—and plenty of enemies, who poisoned him when Temüjin was around nine.

THIS WEEK ONLY

One of his father’s enemies, the Merkits, “ended up going after [Temüjin] once he became old enough,” says Lin. Though they managed to abduct his new wife Börte, Temüjin slipped through their fingers. They chased him to the top of Burkhan Khaldun, a sacred mountain which is part of the Khentii range in eastern Mongolia. “On top of that mountain, it’s said he prayed in every direction to the sky god Tengri, and somehow, from that moment forward, he was able to escape the enemies.”

Temüjin returned from the mountain with his life but without his wife. And so he began to forge alliances in order to defeat the Merkits and rescue Börte. They didn’t just defeat the Merkits––they obliterated them.

(She was Genghis Khan’s wife—and made the Mongol Empire possible.)

From here, Temüjin began a campaign of uniting various clans in the region, amassing soldiers, resources, and respect. In 1206, clan leaders gave Temüjin a new title: Genghis Khan, which Lin says loosely means “the king of everything.” He united Mongolia’s nomadic tribes and created the Mongol Empire, which would stretch from central Asia to parts of China, Persia, and Russia.

Genghis Khan “is the founder of the nation, the father of all Mongols,” says anthropologist Jack Weatherford, author of Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World. “He gave them a united nation, gave it a name, decreed an alphabet, and a set of laws.”

Genghis Khan’s death and secretive burial

In 1227, Khan died leading a campaign against the Xixia Empire in northern China. No one knows the exact cause of his death, but a key source written after he died—TheSecretHistory of the Mongols—gives us some insight. “All we have is one sentence: ‘In the Year of the Boar [1227] Genghis Khan ascended to heaven,’” says Weatherford.

Later chroniclers spun their own stories about his cause of death, ranging from a fall off his horse to an arrow wound and even castration. More recently, scholars have theorized that the bubonic plague may have killed him.

(Why the plague was one of history’s deadliest diseases.)

Genghis Khan’s body was said to have been returned to Mongolia for a clandestine burial. Stories claim that everyone accompanying its procession were killed to keep its location secret, or his followers rerouted a river to protect the site.

“None of it is based on a shred of evidence,” Weatherford says.

Still experts believe the lack of records of his burial was likely intentional to prevent his enemies from desecrating it or disturbing Genghis Khan’s spirit.

“If you wanted to take someone’s land or their spiritual power, you would destroy the tombs of the ancestors that were buried there, because those tombs held the spiritual power of that person,” Lin explains.

But what might Genghis Khan’s burial have looked like? Experts like archaeologist Jan Bemmann, professor of pre-history and early historical archaeology at the University of Bonn, say 13th-century Mongol elites would have been interred in wooden coffins and buried “in remote areas on top of a mountain range.” He says Mongol men like Khan would have been buried with grave goods––such as a “quiver with arrows” or “riding gear”––that identified them as warriors.

Alternatively, Weatherford opines Genghis Khan may have simply been “wrapped in felt” and “buried in the earth” since he was “proud that he lived the same way as his soldiers.”

There’s also the possibility that Genghis Khan wasn’t interred at all. Some Mongols practiced sky burials—a nomadic form of burial “where you’re carried to the top of a mountain and left up there,” Lin says.

Regardless of how Genghis Khan was laid to rest, many believe Genghis Khan his final resting site was Burkhan Khaldun, the holy mountain of safety, transformation, and spirituality for the Mongol people, and now a UNESCO World Heritage site.

But archaeologists can’t simply survey the mountain to look for his tomb. Burkhan Khaldun is a sacred site for the imperial family and therefore part of a forbidden zone, Lin explains. It requires special permission from the state to visit, and access is typically only granted to shamans and Mongolian officials.

The 21st-century tomb hunt

In 2008, Lin proposed using advanced technology––including satellites, drones, ground-penetrating radar, magnetometry, and electromagnetic induction––to get a closer look at Burkhan Khaldun without disturbing the land. His team also enlisted the help of the public to review ultra high-resolution satellite imagery in a pioneering crowdsourcing campaign. This non-invasive approach was key to getting permission to access the mountain.

As part of the National Geographic Society-funded Valley of the Khans project, Lin and his team found thousands of artifacts––including roof tiles, charred wood, and horse teeth––that date to Genghis Khan’s death and just after.

They also located what Lin describes as “a mound” and a “giant shrine” on the mountaintop. “The Mongolians were nomads, so they didn’t build permanent structures,” he explains. So the fact that there is a permanent structure on the mountain suggests it was for ceremonial rather than everyday use.

But could the structure be part of Genghis Khan’s tomb? Lin says there’s no way to know without physically investigating the site.

“It’s not a technological barrier at this point. I think it’s a decision amongst the Mongolian people today to decide whether or not they want to know what’s beneath that structure,” he says.

Does the search for the tomb still matter?

If the tomb of Genghis Khan still exists, experts say it’s more than just a burial site. Lin says to many Mongolian people it “would be a living thing that still embodies the spirit of Genghis Khan.”

Consistent with Mongolian beliefs, the act of “visit[ing] the grave is an effort to call back the spirit from Heaven,” Weatherford explains.

Even after 800 years, the Mongolian people remain protective of their founding father, and this shapes their attitudes toward the grave.

“This is a heritage issue for the Mongolian nation,” says archaeologist Joshua Wright, senior lecturer at the University of Aberdeen. “No one there seems interested in seeing him exhumed or whatever remains exhibited.”

Wright says it’s standard practice in modern archaeology to work with and respect the interests of descendant communities. “If there is little interest in the modern Mongolian nation to dig up Genghis Khan, no one will really go for it,” he adds.

Mongolia’s lack of interest in unearthing the grave brings up questions over what value such a discovery would bring––and what it might take away.

“We should not search for his grave,” Weatherford argues. “[Genghis Khan] said clearly, ‘Let my body die, let my Nation live!’ He was serious about this, and so are the Mongolians. This is not superstition, this is respect.”