Copyright forbes

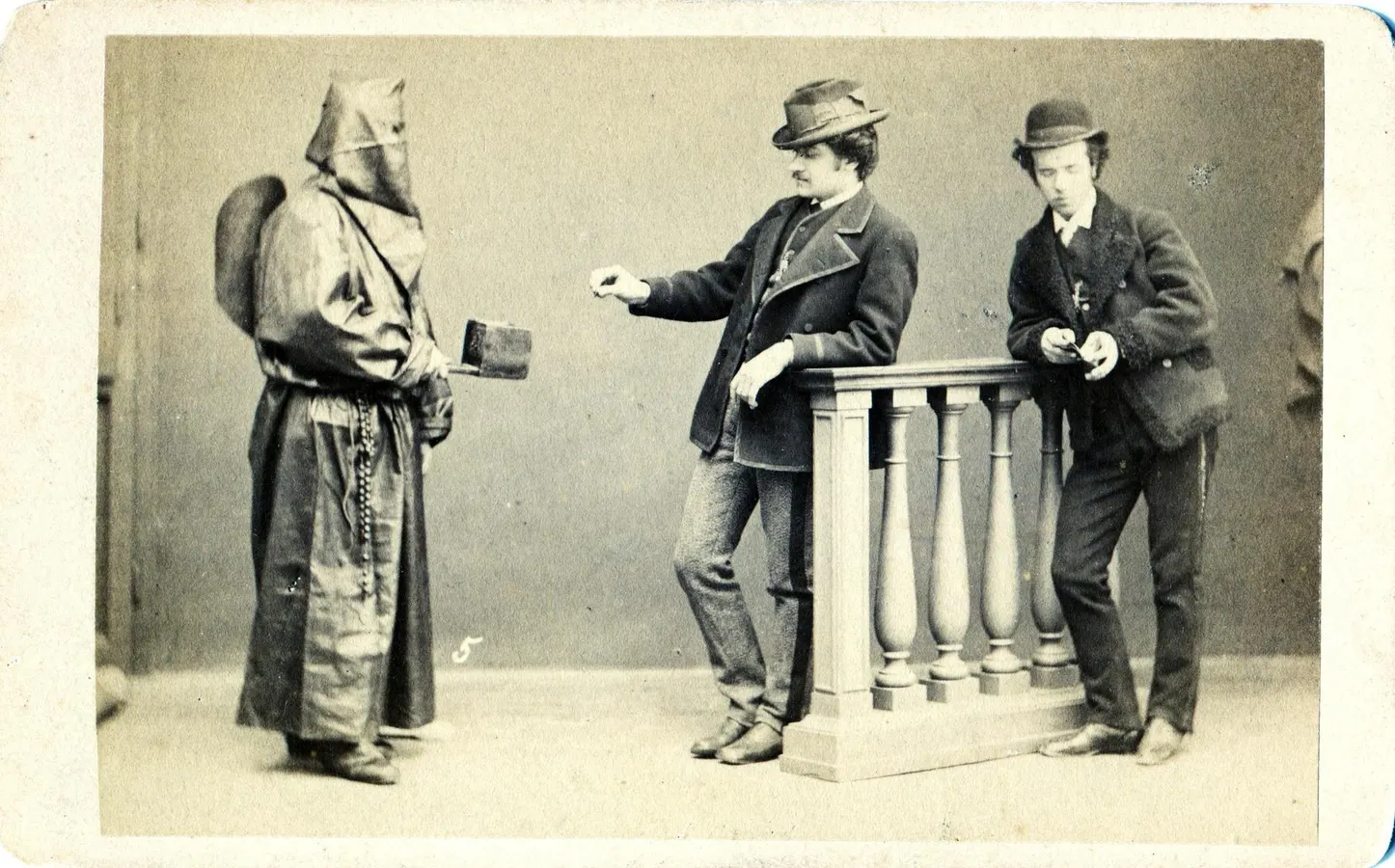

A hooded representative of a Catholic brotherhood asks for donations in his metal box, from Rome, Italy around 1860. (Photo by Transcendental Graphics/Getty Images) Getty Images Is being rich a sign of God’s blessing or a spiritual danger? Is debt a smart financial tool or a sinful trap? These questions go to the heart of how Christians and Western society interpret money, possessions, and obligation. On one hand, wealth can signal discipline, stewardship, and blessing. On the other, it can become a snare, an idol, a source of exploitation. Similarly, debt might be seen as a pragmatic lever of productivity or a trap that burdens the vulnerable and betrays Christian ethics. How Christians have answered these questions has shifted significantly across history. A Historical Overview: Christian And Western Responses When we trace the historical arc, we see at least three major phases: In the early Church and Patristic era, wealth was viewed with suspicion and debt with condemnation. In the medieval and Reformation era, wealth gradually became more acceptable if used well, and debt began to be seen as legitimate under certain conditions. In the modern and American context, wealth is increasingly celebrated as blessing, and debt is normalized as a tool, sometimes with little moral scrutiny. Let’s unpack each era more fully. 1. Early Church And Patristic Era: Wealth As Vice, Debt As Oppression In this period, the dominant Christian voice warned that wealth often threatened spiritual health, and debt or usury, meaning lending at interest, was often seen as exploitation. MORE FOR YOU Church Fathers such as Didache, Basil of Caesarea, Ambrose of Milan, and Augustine of Hippo often sounded the alarm. For example, Augustine, in his Sermon to the rich, put it simply: “That bread which you keep belongs to the hungry; that coat which you preserve in your wardrobe, to the naked; those shoes which are rotting in your possession, to the shoeless.”1 Ambrose was explicit that possessions are not ultimately ours: “The goods we possess are not ours but theirs.”2 The implication was clear: wealth was acceptable only insofar as it was used for the common good. Hoarding, indifference, and pride were dangerous. Debt and Usury: The Old Testament laid the foundation. Laws such as Exodus 22:25 and Deuteronomy 23:19 prohibited interest, illustrating a concern for fairness. In the early Church, charging interest was broadly condemned as taking advantage of the poor. As one summary puts it: “Before the sixteenth century, all Christian writers condemned the practice of charging interest on loans.”3 Debt structured around usury was viewed as a vice. The virtuous life emphasized simplicity, sharing, and stewardship. 2. Medieval And Reformation Era: Wealth As Stewardship, Debt Slowly Respectable As Christianity entered the medieval and Reformation periods, the landscape changed. While the same caution against greed persisted, there was increasing acceptance that wealth itself could be a neutral instrument, even a blessing, provided it was used responsibly. Supporting the church, funding missions, and practicing charity were seen as legitimate uses of wealth. At the same time, indulgences and clerical corruption showed the tension between wealth as virtue and wealth as scandal. Debt and Usury: In the scholastic era, some nuance emerged. Theologians began to allow exceptions such as delayed payment fees or risk-sharing arrangements. With the rise of capitalism in the early modern era, interest began to be seen as legitimate in the context of business productivity rather than simple exploitation. “The schoolmen did not wholly forbid taking interest. They recognized that in some cases, compensation might be due for risk or delay.”4 3. Modern And American Context: Wealth As Blessing, Debt As Pragmatic In the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, especially in the United States, the script flipped in many Christian contexts. The rise of the prosperity gospel is a striking marker. According to historian Kate Bowler: “Millions of Americans believe God wants them to be healthy and wealthy.”5 Her book on the history of the American prosperity gospel shows how this theology combined Pentecostal healing, New Thought mind-power, and an American gospel of individualism and upward mobility to create the belief that financial success is proof of God’s favor. In popular Christian culture, the “American Dream” of upward mobility aligns with spiritual success. If you are disciplined and faithful, you prosper. Wealth becomes a sign of virtue. At the same time, debt, including mortgages, credit cards, and student loans, has become a legitimate and even expected tool in modern personal finance. Debt is seen less as sin than as a strategy. It can be used to invest in education, grow a business, or buy a home. The shame lies only when debt signals irresponsibility rather than strategy. Recap Of The Evolution Early Church: Wealth = danger, Debt = sin or exploitation Medieval and Reformation: Wealth = stewardship, Debt = cautiously permitted Modern and Prosperity Gospel: Wealth = blessing, Debt = normalized tool The Balanced Approach Of Dallas Willard Dallas Willard offers a refined reflection on this trajectory. He warns against simply idealizing poverty: “Many people today are sure in their heart of hearts that it is intrinsically more spiritual to be poor than to be in comfortable circumstances, and certainly than to be rich.”6 He argues that the real challenge is not simply being poor or rich, but what one does with one’s resources. In short, the possession of wealth is not inherently unspiritual. Misuse and trust in wealth are the danger. Willard pushes us toward stewardship, not either extreme. The Better And The Bitter What we have gained: The normalization of wealth has enabled Christians to engage with business, innovation, job creation, and investment without apologizing for success. The recognition of debt as a financial tool enables access to education, housing, and entrepreneurship. The language of blessing, stewardship, and abundance has made discussions of money less taboo in many churches. What we may have lost: The moral critique of accumulation and the spiritual hazard of wealth has largely receded. The early warning from 1 Timothy 6:9-10 may be less front of mind. The protective boundaries around debt are weaker. Easy credit can become a spiritual and financial trap in its own right. The communal and distributive emphasis of the early church, such as sharing goods and alleviating need, has softened in favor of individual consumption, accumulation, and credit-driven lifestyles. The spiritual virtue of simplicity, of redistributing excess, of giving away what is not needed, has less traction in a culture where wealth is a sign of blessing. The Christian narrative about wealth and debt has undergone a dramatic shift from suspicion to stewardship to celebration. For financial planners, fiduciaries, educators, and faith leaders this history matters. It shapes how we teach money, how we understand sacrifice and surplus, and how we interpret debt and leverage. If you are leading a workshop, advising a client, or building curriculum, the question remains: are wealth and debt simply tools to be used, or do they carry moral gravity? The story of Christian thinking invites us to hold both blessing and danger in tension, not to simplify the issues into “rich equals bad” or “debt equals evil,” but to ask: How will we use what we have and owe to love others and not simply for ourselves? 1. Augustine of Hippo, Sermon 50, quoted in “Teachings of the Early Church Fathers on Poverty and Wealth,” Patheos. 2. Ambrose of Milan, De Nabuthe, Book 12, cited in Billy Kangas, “Teachings of the Early Church Fathers on Poverty and Wealth,” Patheos. 3. Institute for Faith, Work & Economics (TIFWE), “Usury in the New Testament and Early Church.” 4. John T. Noonan, The Scholastic Analysis of Usury (Harvard University Press, 1957). 5. Kate Bowler, Blessed: A History of the American Prosperity Gospel (Oxford University Press, 2013). 6. Dallas Willard. The Spirit of the Disciplines (1988). Editorial StandardsReprints & Permissions