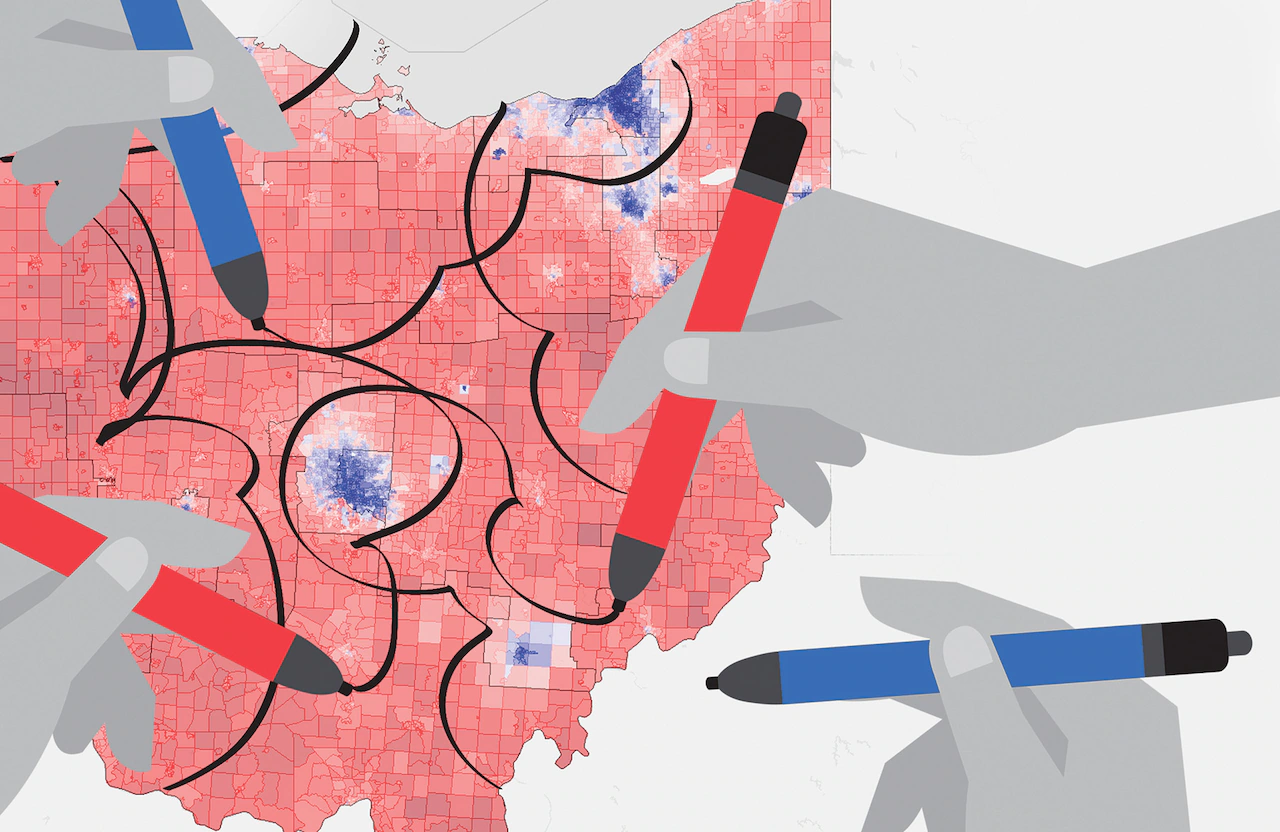

From bipartisanship to power politics: why the promises of Ohio’s redistricting reform unraveled

COLUMBUS, Ohio — In May 2018, after Ohio voters overwhelmingly approved the state’s current process for redrawing congressional districts, the Republican and Democratic sponsors of the proposal declared it would stop gerrymandering and ensure bipartisan collaboration.

“Ohio has decided that partisan motivation will no longer determine the shape of congressional districts,” said the Democratic sponsor, then-state Sen. Vernon Sykes of Akron, in a victory statement along with Republican then-state Sen. Matt Huffman of Lima.

Seven years later, that expectation of bipartisan cooperation has all but vanished. Instead, Republicans will soon be able to ram through new maps to their liking for the second time in four years, whether Democrats like it or not.

Your feedback matters

Do you think Ohio Republicans will end up passing a congressional redistricting map this year that has any Democratic support? Why or why not?

Ohio’s current congressional districts were approved in 2021 without any Democratic votes and were put in place when Republicans ignored a (since-overturned) Ohio Supreme Court ruling that they were unconstitutionally gerrymandered.

This fall, Ohio Republicans are expected to pass a new redistricting plan that is designed to help their party win 12, if not 13, of the state’s 15 U.S. House seats next year – up from the 10 seats the GOP currently holds.

So, what happened?

Huffman, through a spokeswoman, declined an interview request, and Sykes didn’t return a phone call seeking comment for this story. But Republican and Democratic lawmakers, as well as experts and activists involved with the 2018 redistricting amendment, offered several reasons why Ohio’s congressional process hasn’t delivered on what voters were promised seven years ago.

What is Ohio’s redistricting process?

Under the language that Ohio voters added to the state constitution, the Ohio General Assembly has until the end of September to pass new congressional district lines, with support needed from at least 60% of the House and Senate overall and at least half of lawmakers in the minority party (in this case, Democrats).

Stories by Jeremy Pelzer

Feds reject Ohio’s bid to guarantee Medicaid coverage for 152,000 kids through age 4: Capitol Letter

Ohio lawmakers’ texts, emails blocked from public scrutiny under new secrecy law

Ex-Ohio Gov. Dick Celeste endorses Amy Acton to take his old job

But Republicans said no such deal will be reached by Sept. 30 and neither the House nor Senate is scheduled to convene until next month.

On Oct. 1, the seven-member Ohio Redistricting Commission – composed of five Republicans and two Democrats — will then get a crack at passing a bipartisan plan. But if they can’t do that by Oct. 30, the state constitution then allows Republican lawmakers to pass a map without any Democratic votes by the end of November.

The Ohio Constitution also lays out a list of rules that must be followed – at least initially – in any redistricting plan, including that districts must be compact, contiguous, roughly equal in population, and can’t split up counties more than a certain number of times.

If the process drags out until November, though, lawmakers only have to follow another set of rules, such as that they need only “attempt” to draw compact districts and that they can’t pass any map that “unduly favors or disfavors a political party or its incumbents.”

If state legislators or the Ohio Redistricting Commission had passed a congressional redistricting plan with bipartisan support, that map would have been in place for 10 years.

But if a redistricting plan was pushed through by only one party, it must be replaced after only four years. That is why the current, GOP-passed congressional district lines are now being redrawn.

Whatever plan is passed this year — regardless of whether it has bipartisan support or not — will last another six years, until after the 2030 U.S. Census, when the whole process starts again.

A ‘Trojan horse’?

Some Republican critics charge that GOP lawmakers never intended to work in good faith, and that they – including Huffman in particular – knowingly pushed through a redistricting amendment in 2018 that looked good on paper but contained enough loopholes for them to maintain firm control over the process.

“Ultimately, the reform package was a Trojan horse, and it contained enough escape clauses to ensure the satisfaction of the most dark-hearted actor,” said David Niven, a University of Cincinnati political science professor and former speechwriter for former Democratic Gov. Ted Strickland.

Others said that, regardless of Republicans’ intentions in 2018, they ended up flagrantly abusing the new system to push through gerrymandered maps that we have now.

Catherine Turcer, executive director of Common Cause Ohio and a vocal supporter of passing the redistricting system back in 2018, said the amendment had a number of good rules designed to promote compromise and fair redistricting maps.

The problem, she said, is that Republicans flouted the rules, ignoring the Ohio Supreme Court’s directive to draw a new redistricting plan.

“This is not a flaw in the voters. It’s not a flaw in the Ohio Constitution. This is a flaw in map makers,” Turcer said.

When Turcer asked whether the 2018 redistricting reforms could have been strengthened to limit Republicans’ ability to take such action, she replied, “Yes, clearly.”

But, she added, “Would they have just disregarded them? Maybe — and in fact, I think it’s likely.”

Changing incentives

Since 2018, both Ohio and the nation have become a lot more politically polarized. Compromise, long a fundamental part of the American political system, is now widely viewed by both Republicans and Democrats as a sign of weakness and selling out to their political enemies.

Current Ohio lawmakers were elected under a 2023 redistricting plan for state legislative districts that, while passed with bipartisan support, creates only a handful of competitive legislative districts. – that means they’re under more pressure from their respective parties to not agree to any compromise deals.

That pressure is, for Republicans, now coming from the top.

President Donald Trump has been pressing GOP state lawmakers in several red states to more aggressively gerrymander their congressional districts so that House Republicans can build on their narrow majority in 2026. In response, California and some other blue states are also looking to create more Democratic-leaning seats.

Huffman told reporters earlier this month that he hasn’t heard from Trump, though he added that he received calls from “a lot” of other people (whom he didn’t name) with redistricting requests.

Until now, the pressure for mid-decade redistricting has been relatively uncommon in Ohio and other states.

While any congressional map passed this year will last for six years whether it has bipartisan support or not, such pressure may, going forward, twist Ohio’s penalty for passing a map with only one party’s support (having it last for only four years) into an appealing incentive for many Republicans.

“Now it just looks like a system where you can redraw the maps to your partisan advantage every four years instead of every 10 years,” said Sam Nelson, a political science professor at the University of Toledo.

Tom Sutton, professor emeritus of political science at Baldwin Wallace University, said he believes Democrats put too much faith in the idea that Republicans would be so repelled by the prospect of having to undergo another redistricting process in four years that they would prefer to collaborate with Democrats on a 10-year map.

“I think that was naive, quite frankly, particularly in this environment,” Sutton said.

Democratic lawmakers, meanwhile, are also getting pressure not to make redistricting concessions to the Republicans – both from national party leaders and from Democratic congressional incumbents who want to remain in safe seats, said Terry Casey, a veteran Republican consultant from Columbus.

“What advantage do the Democrats get out of cooperating, other than making Joyce (Beatty) and (Shontel) Brown up in Cleveland happy?” Casey asked rhetorically, referring to Democratic members of Congress from Columbus and Warrensville Heights, respectively.

The dynamics of power

There is still a chance that Republicans and Democrats could strike a deal on a new congressional redistricting plan that both parties can get behind. So far, though, there’s little sign that will happen.

Democratic lawmakers proposed a redistricting map that would give Republicans an advantage in eight of 15 U.S. House districts. That ratio corresponds roughly to the average percent of the vote Republican and Democratic statewide candidates got over the last decade — a constitutional stipulation for redrawing legislative districts, but not congressional districts.

When Ohio House Minority Leader Dani Isaacsohn, a Cincinnati Democrat, was asked by cleveland.com earlier this month whether House Democrats would support any redistricting proposal that was more Republican-friendly than that, he replied, “I think anything short of an 8-to-7 map is not fairly representative of the state.”

But state Sen. Jane Timken, a Stark County Republican, who co-chairs the legislature’s new joint redistricting committee, said last week that Republicans deserve far more than that.

“In the relevant time period in which we are to consider partisan races, Republicans have won 22 out of the 23 races,” Timken said during the committee’s first hearing. “I question their logic as to why it has to be 55–45 when clearly the voters of Ohio have strongly supported Republicans over the last decade.”

Sutton said in a one-party state like Ohio, Republicans are just following Machiavelli’s principle that those in power should do everything they can to keep and expand that power.

“I’m not saying that as a critique,” Sutton said. “If you believe that your party represents what your state should be doing and that your voters want, then that’s your basis for saying, ‘We’re going to do everything we can to maintain and expand our majority.’ It’s the dynamics of power.”

If Democrats controlled Ohio government, Sutton added, they would be doing the same thing.

While Ohio’s redistricting process is complicated, he said, its design inevitably boils down to that the party in power has the ultimate say over any new redistricting plan.

“No matter how it’s done, you’re still going to wind up with a partisan process if you’re relying on partisan leaders,” Sutton said.