Copyright gq

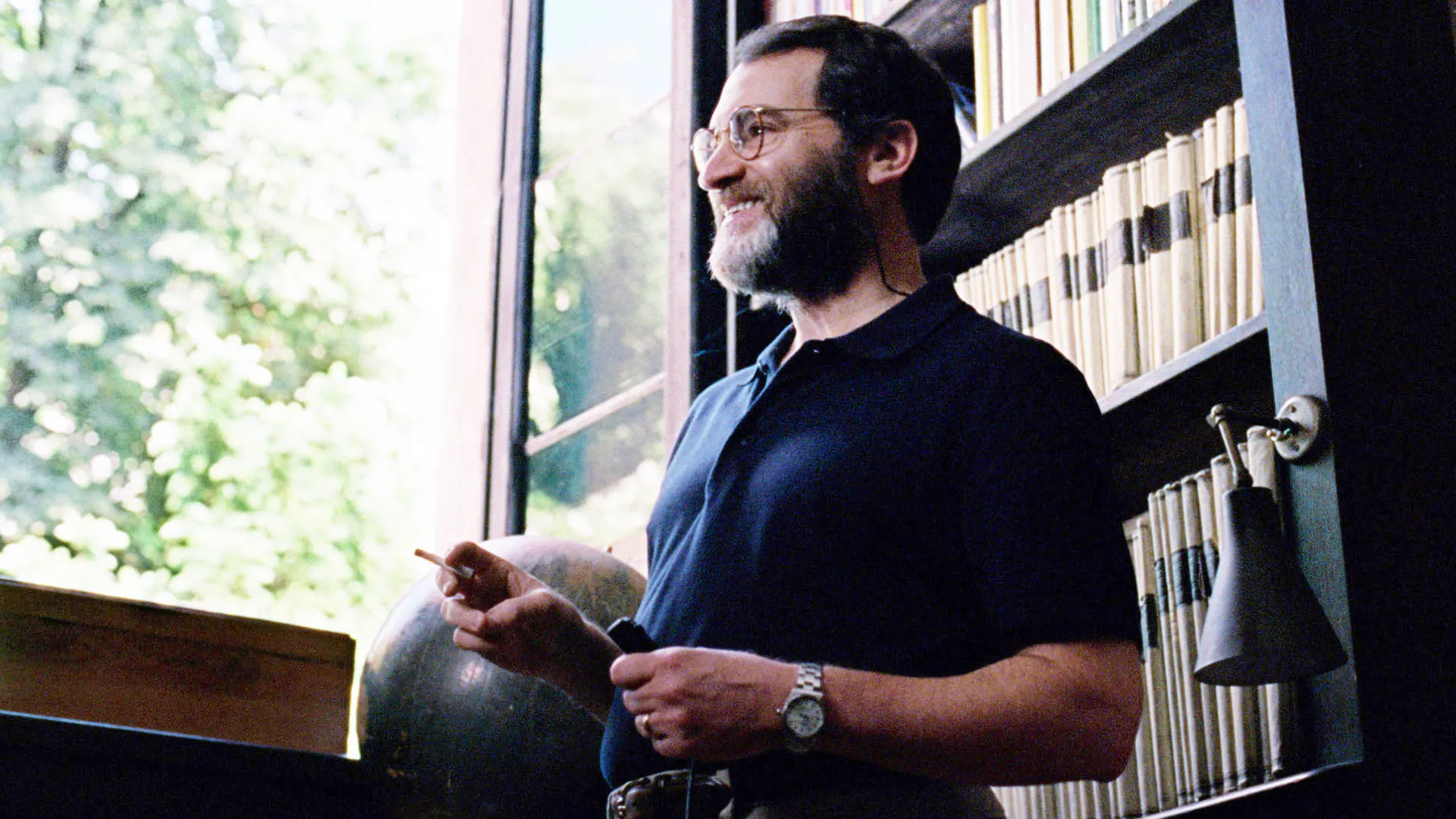

In Luca Guadagnino’s films, you can never trust the boys. A gamine twink might feign naiveté at al fresco family meals, only to eagerly grab his father’s teaching assistant’s junk the first chance he gets. A hopeless ATP burnout might make puppy eyes for a Dunkin’ breakfast sandwich only to intimidate the competition by swinging his dick around the steam room. And that sexually ambiguous pretty boy who walks through cock fights like a Dior model? They might lead you to a psychedelic, ayahuasca-fueled breakdown in the jungle. But in Guadagnino's films, one man you can trust is Michael Stuhlbarg, the veteran character actor who’s had the honor of playing father figure in many of the Italian auteur’s knotty psychosexual dramas. In a cinematic universe that revels in pleasure and its karmic consequences, Stuhlbarg’s men are sturdy and reliable, the sage of grizzled wisdom in a world of chaotic twinks and unreliable narrators. Because of that, the director often chooses Stuhlbarg to deliver his films’ voice-of-God monologues. They’re often comforting grace notes at the end of Guadagnino’s emotionally tumultuous dramas, contextualizing the protagonists’ current turmoil in the broader landscape of their lives. “Michael is a Stradivari,” the director tells GQ. “He can change voice, body language, everything. It’s genius.” Think of Stuhlbarg’s monologue at the end of 2017’s Call Me By Your Name, a conversation between an empathic parent and a queer teenager grappling with his first heartbreak. Stuhlbarg, as the father, memorably doles out wisdom to Timothée Chalamet’s despondent kid. “We rip out so much of ourselves to be cured of things faster that we go bankrupt by the age of thirty and have less to offer each time we start with someone new,” he tells Chalamet’s Elio. "Right now there's sorrow, pain… Don't kill it." The speech has taken on a life of its own through the years—many queer fans of the film hear it as a hug of comfort they never received in their own youths. Stuhlbarg has a similar moment in After the Hunt, Guadagnino’s new drama about a Yale professor whose carefully calibrated life threatens to come apart after a mentee accuses a close colleague of sexual assault. The actor plays Frederik, the husband of Julia Roberts’ character Alma, the professor at the center of a culture war. At the end of the film, after a climactic confrontation that inadvertently sends Roberts’s Alma to the hospital, Stuhlbarg sits with his wife in the dark, reckoning with her traumatic past and providing the only true moment of comfort in the film. “It's always the adult's job to protect the innocence of a child,” he says. GQ recently talked to Stuhlbarg about his four-movie deep collaboration with Guadagnino, how he delivers those speeches, and that unforgettable Italian summer he spent with the cast and crew of Call Me Be Your Name. GQ: You're a veteran of the Luca Guadagnino Cinematic universe by now. In his films, food communicates so much—I think about the prawns in I Am Love, the peach in Call Me By Your Name, the churros in Challengers. And you have two great food moments in this film. There's the tart at the dinner party, early in the movie, and then there's the cassoulet that your character prepares for Alma and keeps in the oven for her. What do you think those two food moments communicate? Michael Stuhlbarg: With the tart, he seems to be listening and watching everything that's going on. He's been sort of fluttering around during the course of things, keeping the energy going and the activity bubbling. And he's watching what's in front of him and he chooses his moment to bring up the tart—and not forgetting the cream. I think it's a way Frederik can show his love to his wife and to their community. I think he made choices early on in their relationship to take a back seat, wanting to encourage and not just heal Alma back to health, but be the support system for her ambitions as well. And I think he enjoys it much more than he may have ever enjoyed trying to toot his own horn, so to speak, in his own career. I think he adores people and I think those particular two elements are touches of his love. And what about the cassoulet? What do you think it communicates? Home and comfort. Work is out there, home is here. Comfort is here. Just sit, relax, let me pour you a nice glass of whatever, have this thing that is made with love that I know you love, and let me provide some ease in your troubled life. I would say as well, it doesn't surprise me that Luca includes food in his films the way he does. Because he's a master chef himself. I was going to ask you about that. When we were making Call Me By Your Name, he would make us these spreads of food away from the set. We would congregate to watch movies—he’d say, ‘You have to see this’—or have meals. It was a play space. It felt like a family room. We would enjoy his hospitality and his cuisine and it would kind of crack open any uncomfortable feelings that anyone might have, in getting to know each other. Because we're breaking bread together, we're eating food together, and the food is delicious and it's of such variety and it's the spice of life. I love that he includes it in films. There's something primal in watching people enjoy themselves in an uninhibited fashion with wine, with dessert, with sumptuous meals. Sounds like a dream. What’s Luca’s best dish? Oh God, my goodness. Well, it can be anything from spectacular vegetables to chicken that’s just [perfect]. You'd have to ask him [the specifics]. The memory is more the camaraderie and the smells and the light and each other and hanging in the kitchen and breathing it all in, which brought it to life then and brings it to life now and sharing it with you. I can't say in particular what one dish might be, but in Call Me By Your Name, it was even those eggs in the morning—the soft boiled eggs in those little containers—and the tins of coffee that were prepared separately as an independent cup, as opposed to having a large pitcher for a lot of people. There was some joyousness on the table every time we had the benefit of sitting at a table. There were a couple of tables during the course of that film as well where it was just decked out. And I think that may have something to do with him wanting some of these stories that he tells, to be an exploration of joy, and what might've occurred on the best summer of your life. I really love how Luca’s used you in your four films together. It kind of feels like you’re the voice of God in these films. In Call Me By Your Name, there’s that incredible speech at the end. In Bones and All, you're the one who says the title. In After the Hunt, you're the grace note at the end, that moment with Julia Roberts’ character in the hospital. In a film that's all hard edges, it’s probably the only moment where someone provides anyone true comfort. I'm grateful to be given the job of ease, to provide some care, some love, some grace, some gentleness. I found that trying to provide comfort in that hospital room, brought back other memories in my life when I've been in hospital rooms as both patient and family member when someone has been not well. In my own experience, I remember coming out of some kind of anesthesia once and understanding that I didn't want anyone to speak loudly. So all of a sudden there was a condition in the scene that we were doing where I wanted very much to be a source of comfort and not one of any kind of noise. So it starts in a particular level of gentleness and I think it stays there throughout, regardless of what I learn or where the scene goes. Working with Julia throughout this film was not just a privilege and an exciting opportunity, but in that scene in particular, the frailty that she managed to inhabit, also colored everything I did, and in a similar sense to the monologue in Call Me by Your Name. We shot it towards the very end of the shoot as well. I had spent a lot of time with that scene, of which actually large portions had been taken out of. It was I think initially almost double digits in terms of pages. In the end, it became unnecessary really in the story that we were choosing to tell. So some of whatever Frederick might have been going through personally didn't need to be articulated in that scene. And I think it offers a loving version of the scene, whereas I think it may been something quite different in another [version]. Towards the end of the scene, all of a sudden we're above them. Coming from a layman like myself in terms of filmmaking, I would want to be as close as I can to the individuals to see what it is they're going through. Finally, when Frederik's trying to understand if Alma can forgive herself for feeling responsible for what she did in the past, all of a sudden by [cinematographer] Malik Hassan Sayeed and Luca's choice to put the camera above us, it’s almost like a voice of God, almost like an act of grace in that sense. Almost like we're looking down on these people who are suffering and learning things about each other. It lifts us out of the situation in some sense and provides the audience with a different perspective in and outside of that room. That moment has the same energy as that speech in Call Me By Your Name, which I'm sure people talk to you about all the time. I was watching it again this morning and I cried as if I was watching it for the first time. And I was like, Wait, I’ve seen this before. Why am I tearing up? That's wonderful. I'm sure people approach you all the time about it. When they do, it's a blessing. This speech, it's been the gift that has kept on giving, throughout the last however many years it's been. I'm grateful when people say things because in the making of movies, it's quite a lonely job. You never know what it is you're making or if it will have any impact on anyone at all. And that piece of text is an asterisk and a grace note in my life. And if it continues to move people, I'm grateful to have been the vessel to have been a part of that moving. Because there's nothing worse than wanting to share and move, share your humanity with the world and then perhaps never hear from it again. So yeah, I'm grateful when I hear that it's moved people. I find your performance in After the Hunt so fascinating. I feel like, on the one hand, you're almost like Ruth Gordon in The Misfits, where it’s like these three people who are miserable, going through all these things, and you kind of pop your head in with humor but also empathy. But on the other hand, the character is also almost pleading for Alma's attention, especially in that scene in the kitchen towards the end. I almost felt like you were the Greek chorus. Tell me about walking that line. That's so interesting. I think he sees what's going on and it resonates with him. And perhaps through Frederik's eyes, the audience has a friendly place to land within those complicated contexts. I think in the previous incarnation of the script, Frederik has a very different story. It was much more along the lines of being someone who had a lot of anger and a lot of frustration about his circumstance with Alma, what they had been through together, how rigorously he cared for her, and perhaps how isolated he felt. So we kind of removed all of that in service to a different story. And that's fine. Yeah, it's still there. I felt it. Even when you’re conducting an invisible orchestra in the kitchen— —there is a through line of frustration. Absolutely. Absolutely. Your second collaboration with Luca was on the documentary Salvatore: Shoemaker of Dreams, where you were the voice of Salvatore Ferragamo. How was working with him on that? Fun. As spontaneous as it is on the set, because you never know the colors he's going to ask you to provide in telling the story and whether or not he wants you to be close to what the real man sounded like, or if it didn't necessarily matter, and certain moments, and how do we make the journalistic language fit, the speed of the picture that's being presented, and what way can we engage the audience through sound? That was a complete privilege, and I watched it again recently and really found the story to be fascinating. But he's a true collaborator, Luca, in that he wants to hear what you have to offer and what it is that you bring to something. And at the same time, I think he has strong ideas of what he would like. And I'm a people pleaser. I just want to be a good student. I want to be an excellent collaborator with him in particular, because I feel like he's given so many gifts to me, so I'm grateful. Can we talk about your voice? I do think it's an important aspect of your craft. Growing up, did you know that you had a special voice? I never think of it that way. But I loved singing—I still love singing. It's a big part of my joy, oddly or not. It comes out in my private time. There's a Shakespeare quote, King Lear says to his fool, “When were you wont to be so full of songs, sirrah?” I honestly tie a lot of my joy and my whimsy to songs and singing. I was in choir. I did musicals first. That's how I found my way into this profession, through song and the Broadway cast albums that my parents had in the house that I grew up with, and that still reverberate in my being. Maybe the next project with Luca is a musical. That would be a thrill.