Fringe economists all the way to the IMF are warning of an ‘economic reset’. What do they mean?

By Alex Blair

Copyright news

You feel it. I feel it. We all feel like something is a bit wonky, no?

Drawing on divergence in sentiment surveys and long-term trends in real income growth, Bravos Research argues something that most of us all agree upon: the financial system is becoming unstable.

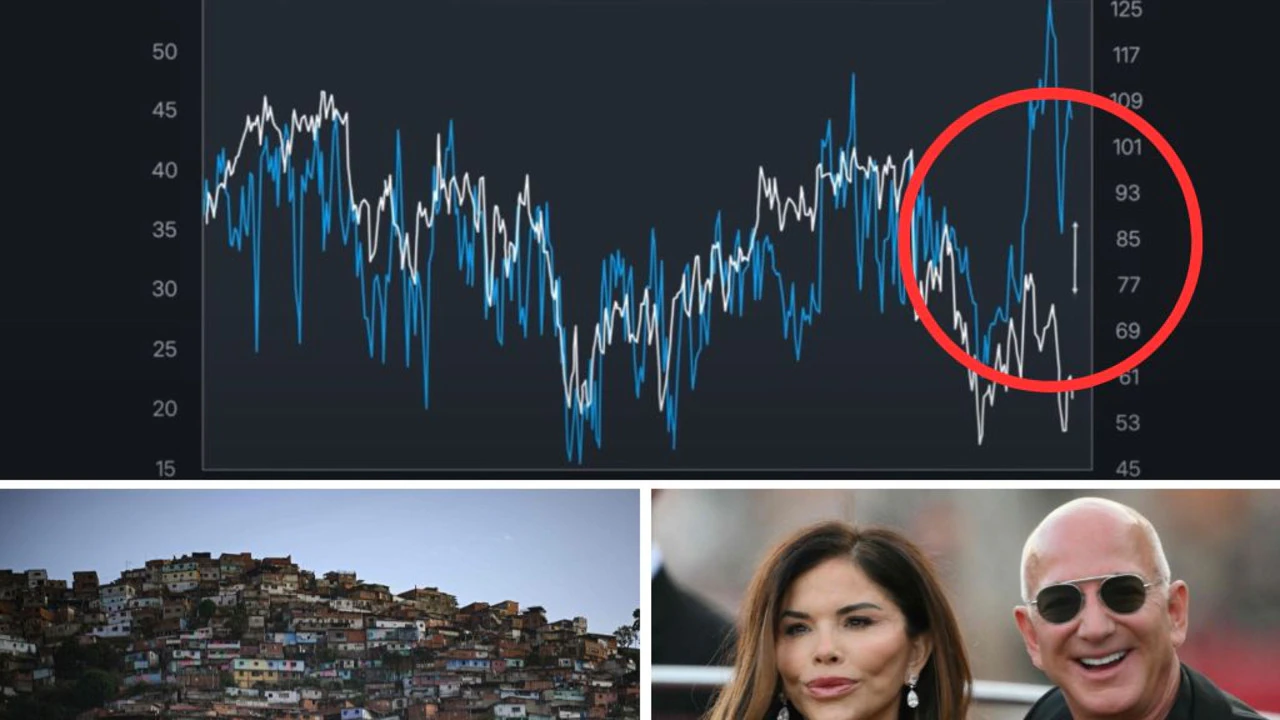

The research firm opens with what it describes as an unprecedented chart comparing two sentiment surveys. It showed that consumer confidence in the stock market is near its highest levels in over 30 years, but sentiment about personal economic prospects is languishing near levels seen during the 2008 financial crisis.

People are optimistic about markets but deeply pessimistic about their own future finances. Bravos sees the disparity in sentiment as a warning sign as investor “euphoria” decouples from real economic expectations.

In blunter terms, it points to a crippling wealth divide that billions of regular humans will never be able to escape from. Not in the traditional sense, anyway.

But the grim findings didn’t stop there.

A second chart presents real personal income growth (adjusted for inflation) over decades, and overlays the historical growth trend from the pre-2008 period.

Up through 2008, real income tracked a steady 2.8 per cent annual trend, since then, actual income growth in the US, and just about every other country that’s loosely tied to the US economy, has persistently undershot it.

Australians are feeling this one harder than most in recent years, with new studies showing our disposable income has dropped more than any other developed nation in the post-Covid inflationary crunch.

Since 2010, real personal incomes have risen only 50 per cent, but the inflation-adjusted return on the S&P 500 has surged nearly 300 per cent, according to Bravos. This figure means that while households consistently feel disappointed and under the pump, asset owners like property magnates and large conglomerates have enjoyed unprecedented gains.

Bravos argues that this gap can’t last indefinitely — the financial economy and asset valuations must eventually realign with the real economy. That is their definition of a potential “reset”.

Since the 1980s, the US household savings rate has declined massively from 13 per cent to 4 per cent, while corporate profit margins have trended ever higher. The same can be said for much of the developed world, as things like higher rents, subscription services, and rapidly rising grocery bills eat into the excess cash in regular families’ bank accounts.

As such, the share of wealth held by the top 0.1 per cent has risen to levels unseen since the 1930s.

In the historical context, Bravos argues that the Great Depression era’s sweeping wealth reversal was triggered in part by dramatic increases in corporate and individual tax rates, reducing profit incentives and suppressing asset valuations. A modern “reset” might come when corporate tax rates reverse their decades-long decline. But the outcome would be far from smooth.

The result of a higher corporate tax rate could see a sharp fall in asset prices, causing massive short-term economic pain before balance is restored.

‘We are entering a new era’

The idea that the globe is rapidly approaching a point of no return is not limited to fringe internet economists. The International Monetary Fund shares similar sentiments.

In April this year, Pierre‑Olivier Gourinchas, the director of the IMF’s Research Department, warned that we are entering a new economic era, with tariff moves and trade disputes introducing major uncertainty.

“We are entering a new era as the global economic system that has operated for the last 80 years is being reset,” Gourinchas said.

“Since late January, many tariff announcements have been made, culminating on April 2, with near universal levies from the United States and counter-responses from some trading partners. The US effective tariff rate has surged past levels reached more than 100 years ago, while tariff rates on the US have also increased.”

Another World Economic Forum survey of chief economists found that a majority expect recent policy shifts to heighten recession risks and create long-lasting disruption.

The World Bank has meanwhile revised trade growth forecasts downward, citing rising protectionism.

The Economist Intelligence Unit warns of a US slowdown, stagflation risk, and fragile financial conditions amid geopolitical turbulence, while analysts at the CFA Institute highlight how tariffs, trade friction, and structural divergences are contributing to an environment of increased fragility.

Observers point to artificial intelligence, geopolitical fragmentation, supply-chain reconfiguration, and political polarisation as non-traditional risks that could magnify economic stress in unforeseen ways in the near future.

Global wealth inequality is getting worse

It might not come as a surprise, but the figures on income inequality will make your eyes water.

Globally, the wealthiest 10 per cent of people earn more than half of all income. In many analyses, the top decile’s share is estimated at around 50-52 per cent of global income.

By contrast, the bottom 50 per cent of people collectively earn only about 8 per cent of global income. That’s around four billion people living on under 10 per cent of the money flowing through the international system.

In many regions, the income share of the top 10 per cent is even higher relative to what earlier statistics suggested, once tax data and under-reported incomes are accounted for.

The world’s richest one per cent, or those with over about $1.5 million in net assets, hold nearly half of global wealth.

Many people in low-and middle-income countries hold negligible wealth in comparison. For example, adults with less than $15,000 in assets make up a giant share of the world’s population, yet they hold less than 1 per cent of global wealth.

How’s it looking in Australia?

Australia likes to think of itself as a “fair go” nation, but when you look past wages and into wealth, the divide is staggering. The myth of the “lucky country” has faded for the next generation as they watch the gap grow year by year.

The bottom 20 per cent of Australians hold just 0.4 per cent of the country’s total wealth, while the top 20 per cent control a massive 63.2 per cent.

Over the past two decades, the top 10 per cent of households have pulled far ahead. Their average wealth has grown from about $2.8 million to $5.2 million, an increase of 84 per cent.

For the lowest 60 per cent of households, average wealth rose from $222,000 to just $343,000, a far more modest 55 per cent. Nearly half of all wealth accumulated since 2003 (45 per cent) has landed in the pockets of the top 10 per cent.

Among younger households, the trend is even more out of whack.

Australians under 35 who sit in the wealthiest 10 per cent, mostly those who have inherited from rich relatives, have seen their fortunes more than double, rising from roughly $928,000 to $2 million. By contrast, the lowest 60 per cent of young households have seen almost no movement at all, going from $68,000 to just $80,000 in two decades.

The wealthiest 20 per cent of Australians control 82 per cent of all investment property, over 70 per cent of superannuation assets, and more than half of the nation’s housing wealth.

For those locked out of property or unable to accumulate super early, the chances of bridging the divide are rapidly evaporating.

Since 2004, the share of wealth held by the bottom 40 per cent of Australians has fallen from 7.8 per cent to just 5.5 per cent. Meanwhile, the moneyed one per cent of households now hold almost a quarter of the country’s wealth, and the top 10 per cent command 57 per cent.

On paper, income inequality in Australia looks relatively moderate, thanks to the tax and transfer system, but wealth inequality tells the real story.

As assets compound, capital builds upon itself, and those at the top kick back and watch their CommBank digits multiply while the majority tries to keep up the pace on the rigged treadmill they were born on.