Copyright The Denver Post

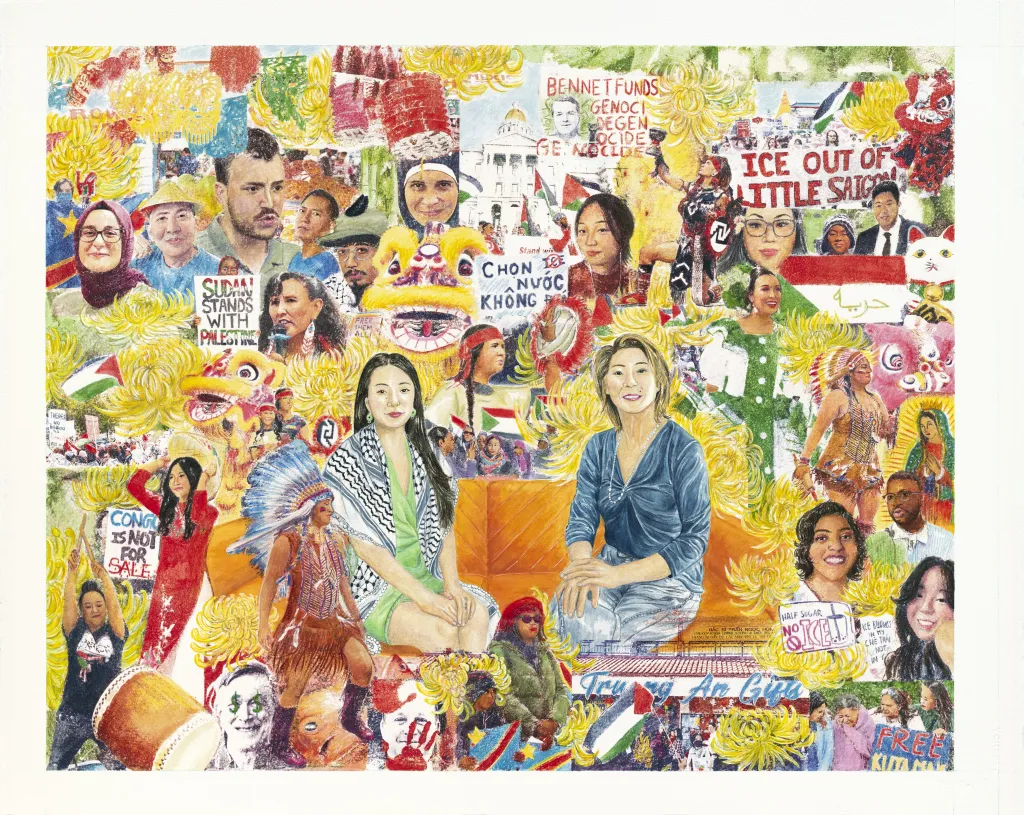

A coalition of First Amendment rights groups is criticizing the History Colorado Center this week, saying the organization violated its own taxpayer-funded, community-centric mission by removing a painting that had been planned for its latest exhibit. “None of Us Are Free Until All of Us Are Free,” by Denver artist and illustrator Madalyn Drewno, shows two members of the Little Saigon business district, Joie Ha, the executive director of Colorado Asian Pacific United (CAPU), and her mother, Ivy Ha, seated together. All around them are images of human rights struggles across the globe, including ICE raids in the United States, violence in the Congo and Sudan, immigration debates and the war in Gaza. U.S. Sen. John Hickenlooper’s face appears with dollar signs scrawled over his eyes, while Sen. Michael Bennet’s face is surrounded by the words “Bennet funds genocide,” and Gov. Jared Polis’ face is covered by a red handprint. The images critique the politicians as ignoring or enabling violence against marginalized and oppressed communities. While the painting (and two others by Drewno) was supposed to be part of History Colorado’s “Big Dreams in Denver’s Little Saigon” exhibition, which opened on Oct. 20, the state-funded nonprofit decided at the last minute not to include it. Its justification is that the painting’s imagery and its inclusion in a state museum could constitute a violation of the Fair Campaign Practices Act, which prohibits government institutions like History Colorado Center from making contributions to a candidate running for office. Jason Hanson, chief creative officer with History Colorado, said the painting, commissioned and paid for by CAPU, “was delivered weeks before the exhibition opening and was significantly different from what had been proposed and reviewed through the collaborative planning process,” according to a statement provided to The Denver Post. The initial sketch did not feature the political faces or messages, according to a Denver Post review. “The artwork unexpectedly included depictions of current candidates for office, and our long-standing practice is not to use public funds or resources as a platform for or against active political candidates, parties, and ballot issues,” he wrote. Bennet is currently running for Governor, while Hickelooper is running for a second term in the Senate. Hanson called History Colorado’s practice “viewpoint neutral” and informed by the Fair Campaign Practices Act, the Hatch Act, the IRS ban on political campaigning for 501c3 organizations, personnel policies, and guidance from professional organizations like the American Association of Museums. History Colorado is a state agency under the Colorado Department of Higher Education, with about half of its $40 million annual budget for last year coming from limited gaming revenues, according to its most recent annual report. About $8 million in federal and state funding also supports its mission of historic preservation and storytelling that “centers communities, deepens knowledge, and catalyzes the transformative power of history,” according to its website. Drewno still sees History Colorado Center’s decision as censorship, and she voluntarily reclaimed her other two paintings, commissioned by CAPU, “Letting Go + Holding On” and “Love Is All About Good Timing,” instead of letting them remain in the exhibit. She’s backed by the National Coalition Against Censorship (NACA), the American Civil Liberties Union Colorado, and the Foundation for Individual Rights, which addressed a letter to History Colorado president and CEO Dawn DiPrince that says the organization’s action misinterprets state law and stifles free speech. “History Colorado Center invited, and then disinvited, a work of art under the false pretense that displaying art constitutes a campaign contribution,” Elizabeth Larison, director of the Arts and Culture Advocacy Program at NACA, told The Denver Post. “Not only is their legal argument not credible, it is deeply dangerous, because it would mean that the government would be able to suppress and limit the circulation of artwork that contains any kind of political commentary or criticism of elected officials — protections that are at the very core of the First Amendment.” Drewno and CAPU deserve a formal apology, she added. CAPU acknowledged that the political content wasn’t included in Drewno’s initial proposal, but Jasmine Chu, CAPU’s programs and communications manager, said the organization, which funded the exhibit, pushed for a compromise. “Since its removal, we have remained committed to opening dialogue, opportunities for repair, and solutions that are mission aligned,” Chu said. “(CAPU) is a storytelling organization. Our mission is to unearth, preserve, and celebrate local Asian Pacific Islander American histories. We are grateful for our relationships with our community knowledge bearers, artists, and institutions like History Colorado that make the work possible.” She added that she hopes people can still find value in the exhibition and the related Little Saigon Memory Project, which collects oral histories of the Asian-American community along Federal Boulevard between Alameda and Mississippi avenues. History Colorado Center’s move is unusual in the museum world, where meticulous planning typically supports exhibitions with a patchwork of loans from public and private collections. More common in recent years, however, are political concerns over the content of paintings as well as the Trump administration’s targeting of arts funding and its threats related to “woke” art. Last year, Indigenous Colorado artist Danielle Seewalker’s planned public mural in Vail was cancelled after a resident complained about a pro-Palestinian artwork on Seewalker’s Instagram profile, which led to the overall cancellation of her artistic residency in Vail. Like Seewalker, Drewno told The Denver Post that her artwork is designed to spur discussion, not division. “I created my piece to really ask ourselves to imagine what our solidarity could look like — and in a way that expands beyond just our small community in the Little Saigon District,” Drewno said. “What would it look like to really recognize our interconnected struggles? It’s not enough to just have these inclusive liberal representations because it avoids talking about the root causes.” As a next step, Drewno is looking to create a grassroots exhibition of artworks that were either censored by or rejected by government institutions. She wants to send the message that artists don’t need the validation of public institutions to speak freely while challenging systems of power and oppression. “And it won’t be limited by donors or funders who have interests that are against the people,” she said.