Copyright zimeye

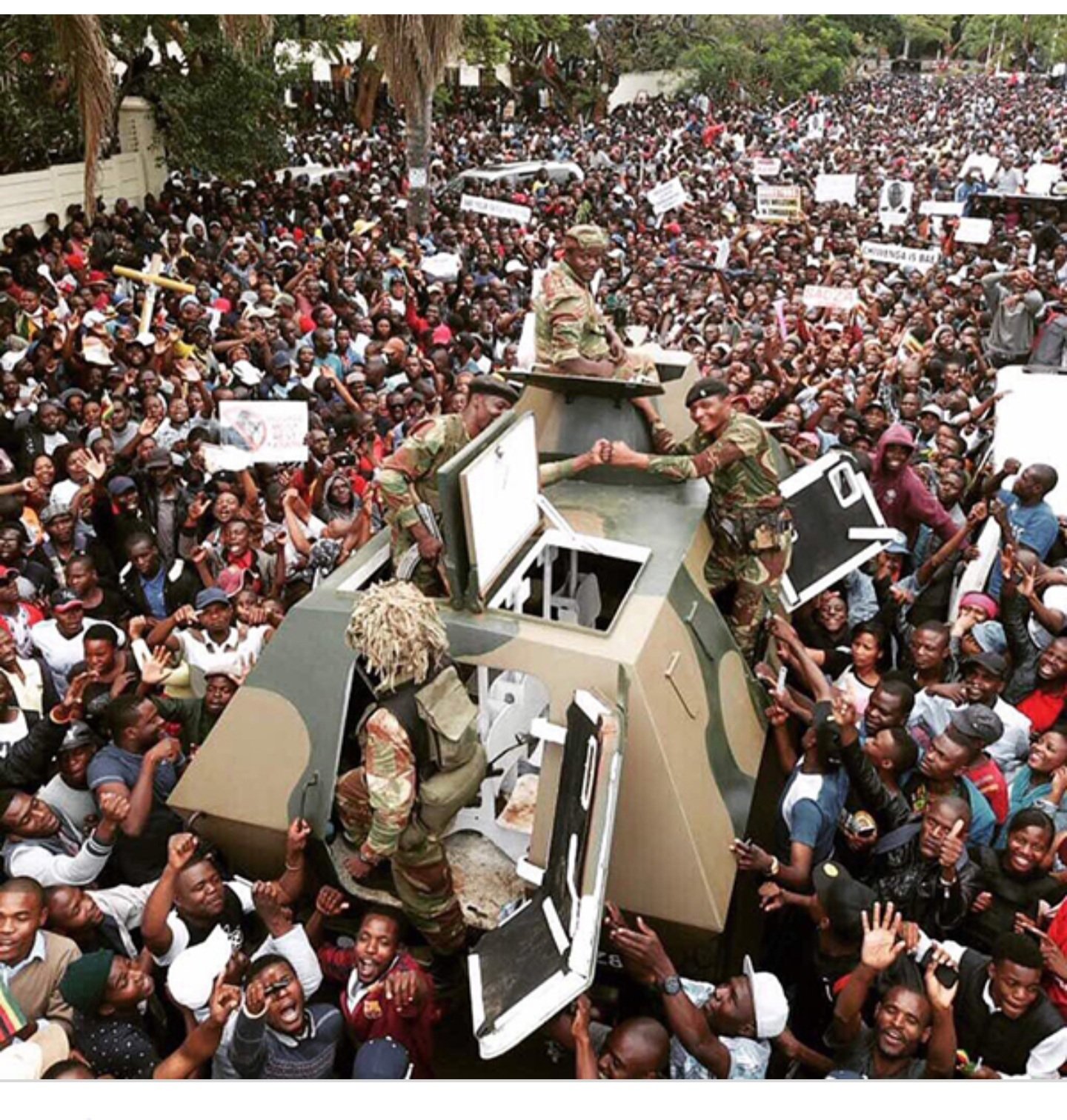

By a Correspondent — Former Central Intelligence Organisation (CIO) chiefs Happyton Bonyongwe and Lovemore Itai Mukandi have revealed the extent of political interference in Zimbabwe’s intelligence services, warning — through their own accounts — of a recurring pattern that could culminate in another military-assisted transition similar to the 2017 coup. Their memoirs, published earlier this year, detail how the CIO became deeply entangled in ZANU-PF’s succession politics, transforming what should have been a professional national institution into a partisan tool for preserving political power. Analysts say the revelations expose the same institutional weaknesses and factional rivalries that triggered Mugabe’s ouster — and could once again threaten stability as the Mnangagwa-Chiwenga succession battle intensifies. In an opinion piece published by ZimEye, Professor Allen Munoriyarwa of Walter Sisulu University argues that the two former spy chiefs’ accounts demonstrate how “the intelligence agency serves not national interests but the narrow political objectives of the ruling party.” He warns that the ongoing infiltration of state security structures into internal ZANU-PF conflicts “echoes the same patterns that preceded the 2017 coup,” reflecting what he terms “institutional capture and parallel intelligence operations.” Below is an abridged version of Professor Munoriyarwa’s opinion piece: By Professor Allen Munoriyarwa-This year has been a pivotal one for Zimbabwean politics. The ongoing succession dispute between the President and his Vice President shows no sign of abating. All signs point to a dog-eat-dog contest in the coming years, with the potential for a brutal, even violent, conclusion. To understand the unfolding crisis, let us rewind to February 2025. Former CIO Director-General Happyton Bonyongwe—the longest-serving head of the country’s state security service under the late ex-president Robert Mugabe—launched an autobiography titled One Among Many: My Contribution to the Zimbabwean Story. Almost immediately after, another former CIO Deputy Director-General, Lovemore Itai Mukandi, published his own tell-all book, How Mnangagwa Blindsided Robert Mugabe and Grabbed Zimbabwe. It now seems fashionable for former spy chiefs to document their organisational experiences. The “icing on the cake,” however, came with the ruling party’s annual conference, which served as comic relief amid the release of the two explosive books. At this ZANU-PF conference, the party resolved to extend the President’s tenure to 2030. Notably, in Bulawayo last year, Patrick Chinamasa had announced the same resolution. These three developments are deeply interlinked, and their coincidence bodes ominously for the country. Yet, it is hardly productive to dwell on the ZANU-PF conference itself—it has become a predictable annual ritual, recycling the same hollow rhetoric. The usual party stalwarts shouted the same slogans, applauded by hungry, unemployed, and disillusioned youths, cheering proclamations of imaginary economic “progress.” The Mutare and Bulawayo conferences, stripped to their core, are about one thing: the vicious succession dispute between President Mnangagwa and Vice President Chiwenga. The two men, to their credit, have not publicly exchanged blows—at least not yet. But their proxies are already at war on their behalf. We are repeatedly told that the President has no interest in a third term. He has reportedly assured Chinamasa and others that he is a constitutionalist. For those who lived through November 2017, this claim may sound ironic—but that is beside the point. One wonders: where are the “third-termists” drawing their energy from? This crusade would have died a natural death had the President emphatically declared his intention to step down in 2028. The fact that the debate persists suggests encouragement from within. Some even suspect that 2028 is merely a stepping stone toward abolishing term limits altogether. Otherwise, why all this noise and polarisation over just two years? As in 2017, the final arbiters of this conflict will not be ZANU-PF’s rank and file—long accustomed to uncritical obedience—but the state’s coercive institutions. Already, movements within the Central Intelligence Organisation (CIO) hint at such an outcome. What makes this fight particularly dangerous for ordinary Zimbabweans is the involvement of the intelligence agency itself. The two books mentioned earlier expose the CIO’s long-standing entanglement with partisan politics. Both authors confirm that the institution serves not national interests but the narrow political objectives of the ruling party—just as the military did during the 2017 coup and arguably continues to do today. In Bonyongwe’s memoir, he admits trying to persuade Mugabe to retire—even seeking a meeting with Grace Mugabe to do so. This was not the work of a national intelligence head but that of a political operative. Was Mugabe’s succession a national security issue? Clearly not. If it were, why did ZANU-PF nominate him as a candidate in 2013, and why did subsequent party congresses endorse him despite his advanced age? Mukandi’s book goes further. He alleges that President Mnangagwa continued to run a parallel CIO structure after leaving the Ministry of State Security in 1999, holding meetings in Gweru with faction-aligned operatives who briefed him behind Mugabe’s back. These revelations expose the deep partisanship and capture of the intelligence services. The November 2017 coup revealed the extent of institutional capture in Zimbabwe. The army, after defending Mugabe for 37 years, suddenly turned against him. The CIO played its part, while ordinary citizens were mobilised to march against Mugabe under false pretences. Reports later emerged that some security and intelligence officers involved in the coup were promised money and gold—transforming them from professionals into mercenaries. Mukandi’s allegations about the existence of a parallel intelligence structure are therefore deeply alarming. They highlight how politicisation and personalisation of intelligence can destabilise a nation. Mugabe himself was accused of maintaining a similar structure during his rule. The repetition of such practices points to systemic failure in the oversight and governance of security institutions. To prevent further deterioration, Zimbabwe must first ensure that intelligence officers are properly remunerated. Underpaid and impoverished agents can easily be co-opted into political or factional service. Furthermore, ZANU-PF’s reported involvement in recruiting party-aligned youth into the CIO compounds the problem—it embeds partisanship within the institution itself. This raises a fundamental question: can citizens still trust such institutions? And if so, on what grounds? Zimbabwe urgently needs to reflect on the kind of intelligence agency it desires—one that is professional, well-compensated, and non-partisan. The fact that individuals can run parallel intelligence structures or that top spies intervene in party succession disputes shows how deeply flawed our oversight mechanisms are. We need a civilian-driven oversight model for intelligence institutions—one that monitors their welfare, budget, and conduct to shield them from political interference. Such reform would require a bold constitutional process involving civil society and independent experts. Admittedly, those benefiting from the current politicisation—particularly within ZANU-PF—would resist it, fearing the loss of their grip on power. But this reform should not be viewed as an attack on any political party. It would, in fact, strengthen national institutions and safeguard democracy. ZANU-PF’s greatest illusion is the belief that it will rule forever. It will not. Therefore, the party itself would benefit from institutions that serve the nation rather than transient political elites. The convergence of an unrestrained, partisan intelligence apparatus and a volatile succession struggle within ZANU-PF is a ticking time bomb. For a nation already weighed down by poverty, unemployment, and despair, the spectre of collapse looms large. How we reform and depoliticise our intelligence agencies will determine whether Zimbabwe retains even the remnants of democracy—or slides further into authoritarian decay. Professor Allen Munoriyarwa is a Professor of Journalism at Walter Sisulu University, South Africa. This article forms part of an eight-country research project titled “Public Oversight of Digital Surveillance for Intelligence Purposes: A Comparative Case Study of Oversight Practices in Southern Africa,” supported by the British Academy Global Professorship Programme through the University of Glasgow.