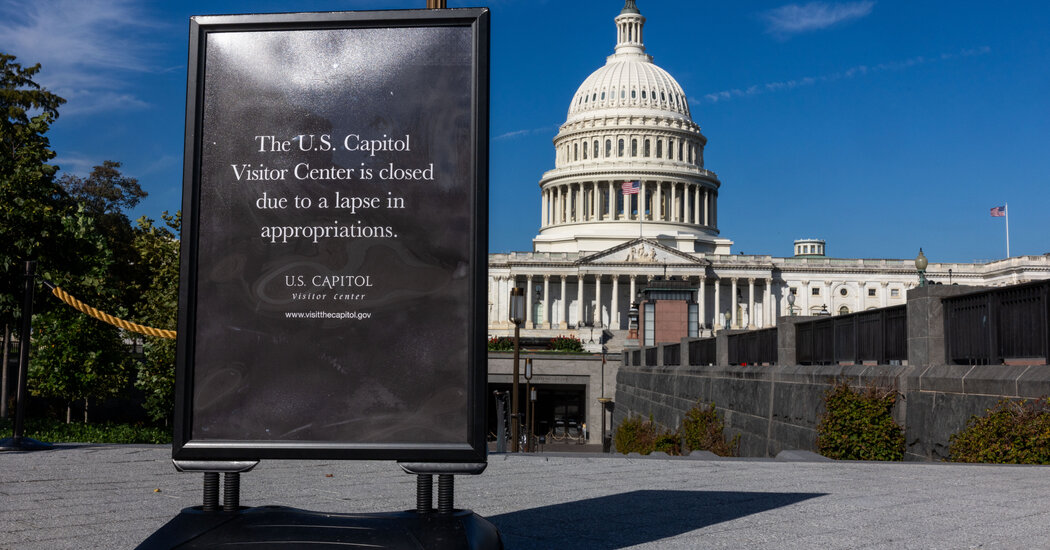

The first government shutdown in nearly six years left federal agencies in flux and many of their employees in a state of confusion on Wednesday, as they received last-minute and conflicting instructions from managers.

Even though the likelihood of a shutdown has been high for months, agencies were late to post their contingency plans compared with previous years, leaving employees and the public in the dark about what to expect. And internal guidance to work forces in some cases was not consistent with the official plans. Some employees who expected to be furloughed learned on Wednesday that they had to report to work.

But despite the uncertainty inside the government, the initial ripple effects across the country were scattered and limited.

There was no major disruption to air travel. The Internal Revenue Service answered calls from taxpayers. And federal agents arrested immigrants who showed up for routine court appearances in Lower Manhattan.

But the impact was felt elsewhere. The Jimmy Carter Presidential Library in Atlanta was closed, and visitors got a quick civic lesson: Presidential libraries are operated by the federal National Archives and Records Administration, which furloughed more than half of its staff.

“We thought it was privately funded, or we would have come yesterday,” said Cindy Mobley, 64, of Baltimore. Ms. Mobley and her husband were in town visiting their son, a freshman at nearby Emory University.

Not being able to visit the museum, Ms. Mobley said, “is a small price to pay if it leads to something better for all of our citizens.” She said she supported congressional Democrats who are refusing to agree to a spending plan that does not restore funding for Medicaid and extend health insurance subsidies.

For Chris Hill, of New York, the first day of the shutdown brought an unprompted message from the Department of Veterans Affairs. He said he had been working with the agency to resolve a benefits issue regarding his late father and was surprised to see the message informing him that the government was shut down, noting that some agency services would not be available.

The message also blamed Democrats for the shutdown, which Mr. Hill said also caught him by surprise.

“It was such a political and one-sided message sent out by a department that is supposed to deal equally with veterans, regardless of their political opinions,” he said in an interview.

Similar political responses have come from other agencies, marking what many believe to be the first time an administration has used the bureaucracy to deliver blatantly partisan messaging during a shutdown.

Legal experts say doing so violates a federal law, the Hatch Act, designed to ensure that the federal work force operates free of political influence or coercion. And many federal workers expressed discomfort about being drawn into the political morass.

And for at least the first week of the shutdown, the 74,299 employees at the Internal Revenue Service are working as though nothing has changed. The agency is able to do this because of a special pot of money created by Democrats in 2022 intended to fund operations when appropriated funds have run out.

The tax agency lost 25,000 employees this year under the Trump administration’s efforts to shrink the size of the government. It is racing to prepare for next year’s filing season, when many Americans could feel the effects of new tax cuts passed by Republicans this summer.

It is not clear how many people at the tax agency will continue working once the special fund is depleted. But until then, if people call the agency with a question about the upcoming extended filing deadline on Oct. 15, for example, they should be able to receive a response as if the rest of the government were not shut down.

But not all agencies were as clear and transparent as the I.R.S. when it came to telling employees what to expect on Wednesday.

Some employees at the Environmental Protection Agency were surprised late on Tuesday to learn that they would not be furloughed, as expected. The agency’s shutdown plan called for just 11 percent of the staff to continue working. Instead, the employees were told they would continue to work on activities that have yet to run out of funding.

Typically, when operations are able to continue during a government shutdown because of leftover funds, that is noted in an agency’s contingency plan. This was not the case for the E.P.A.’s plan, though, and employees wondered whether they would be working without pay.

“Continue to work on initiatives as directed by your leadership,” the head of the agency’s air office, Aaron Szabo, said in a Wednesday memo to his staff, which was reviewed by The New York Times. He advised that employees would be “notified if there is any change in status.”

Employees from some agencies noted other inconsistencies and problems, including how little notice they received about plans ahead of the shutdown.

A National Park Service employee said messaging was chaotic and changing well into Wednesday afternoon. Some employees were told that they were furloughed but that their status could change at any time.

The Statue of Liberty, which is operated by the National Park Service, was open on Wednesday, but funding was expected to run out in the coming days.

The Justice Department asked judges across the country to pause many civil cases because the department did not have the staff to handle them during the shutdown. While this is a routine outcome during a funding lapse, if the shutdown goes on for weeks it could have a real impact on cases that judges have agreed to postpone, including those challenging Trump administration policies that have been moving through the court system.

Organizations that sued the administration over funding cuts may be forced to change course and try to settle cases, said David Super, a law professor at Georgetown University.

Other federal programs that the public relies on will also run out of funding if the government shutdown stretches into days or weeks, including federally funded child care and federal grocery vouchers for low-income mothers and children.

If the shutdown drags on, the Food and Drug Administration may have to stop some routine inspections of food and medication facilities.

Lisa Friedman , Christina Jewett , Andrew Duehren , Maxine Joselow , Alessandro Marazzi Sassoon and Luis Ferré-Sadurní contributed reporting.