By Mark Magnier

Copyright scmp

Gilda Banugan of Davao City in the Philippines has worked for over a decade as a housekeeper in Taiwan.

While the money is much better than she could earn at home, it carries a cost: the knowledge that she is living in one of the world’s most dangerous flashpoints, facing the looming threat of an attack by mainland forces.

“If you ask many Filipino migrant workers, in case something happened are they going back to the Philippines or not, most likely the answer is no, they want to stay put in Taiwan,” said Banugan, 41. “Because, how can we survive even if they tried to rescue us?”

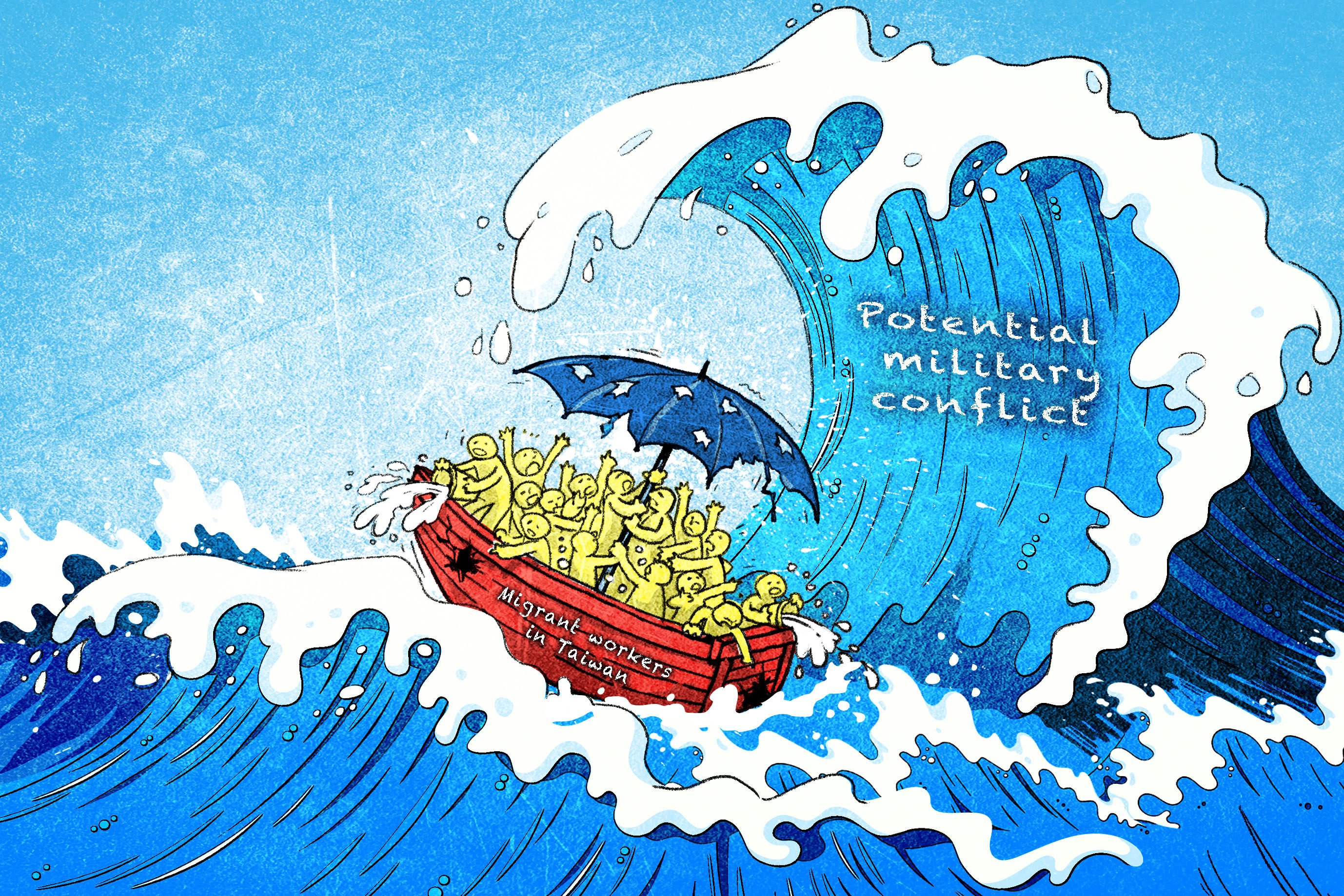

With tensions mounting across the Taiwan Strait, the fate of the island’s nearly 1 million foreign residents is often overlooked amid the geopolitical calculations.

For many migrant workers, that awakens fear that they could be collateral damage, caught in the crossfire and left wondering whether they will be rescued.

Taiwan had 849,777 foreign workers at the end of July, according to the Ministry of Labour’s Workforce Development Agency, most from Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam, helping to ease labour shortages in manufacturing, construction, fishing, hospitals and home care for Asia’s eighth-largest economy.

With dependants and others, the number exceeds 950,000, some 4 per cent of Taiwan’s population.

But foreign workers often face second-class treatment under Taiwanese labour law, as well as sexual and physical abuse by employers.

“This population will be severely negatively affected in a military conflict, given that they are already marginalised in a peaceful Taiwanese society,” said Ava Shen, a Eurasia Group analyst.

“Taiwan will likely take care of the Taiwanese first, and then at the same time try to coordinate repatriation plans with Southeast Asian governments.”

Among the most vulnerable are foreign fishers working on Taiwan’s 2,000 deep-sea vessels, a US$1.5 billion annual business.

Trapped at sea, they are particularly vulnerable to exploitation, highlighted in a September 2022 US Labour Department report that called out Taiwanese fish products over child and forced labour abuses.

They are also on the front lines of Beijing’s grey zone tactics, as seen in July 2024, when the Chinese Coast Guard detained the Taiwanese vessel Da Jin Man, leaving several Indonesian crew members caught in the stand-off.

Despite their huge dependence on remittances, most Southeast Asian governments have been relatively muted about rescue plans, wary of provoking Beijing.

Clearly, evacuating tens of thousands of citizens during a conflict would present immense logistical and geopolitical hurdles.

The Philippines, a US ally and the closest geographically to Taiwan, has been the most forthright.

“If something happens to Taiwan, inevitably we will be involved,” said Armed Forces of the Philippines Chief of Staff General Romeo Brawner in April. “We will have to rescue them.”

Indonesia has also pledged, after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine drew parallels with Taiwan, to rescue its citizens in a cross-Strait crisis, while Vietnam and Thailand have been more circumspect. And none have provided details on potential flight, shipping routes, logistics or collection points.

“A contingency plan has been prepared in collaboration with the Indonesian Economic and Trade Office in Taipei,” Judha Nugraha, a director with Indonesia’s foreign ministry, said in 2023, adding that Jakarta was “actively monitoring” developments.

Successful evacuations by under-resourced Southeast Asian nations would depend on the amount of advance warning, the type of Chinese military action, Beijing’s willingness to spare non-combatants and whether global relief agencies assisted, potentially risking their own staff, analysts said.

“The number of Indonesians that live in Taiwan is more than 300,000,” said Broto Wardoyo, international relations chair with Universitas Indonesia. “I don’t think any plan would be able to safely transport that many.”

Wardoyo said the Taiwan-Asia Exchange Foundation officials told him in Taipei in August that many Indonesians would help defend Taiwan against any mainland attack. Given close Taiwan-Indonesian ties and many marriages, that “is not baseless”, he added.

The Foundation did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Southeast Asian nations have successfully evacuated citizens from recent wars and natural disasters in Ukraine, Libya and Iran. But those were smaller operations that often included UN assistance, which might not be available in light of the UN’s one-China policy.

A blockade by China – seen as a likely scenario given recent naval encircling exercises around the island – would make any evacuation particularly difficult.

“Whenever this happens, there’s no way for civilians, overseas foreigners to take aeroplanes and go away,” said Scott Huang, associate investment researcher at the Hsinchu Science Park Bureau.

“As soon as the [Taiwanese] government declared martial law and closed every harbour and every airport, no party will leave.

“Taiwan has fears like this.”

Beijing sees Taiwan as part of China to be reunited by force if necessary. Most countries, including the US, do not recognise Taiwan as an independent state. But Washington is opposed to any attempt to take the self-governed island by force and is legally bound to aid in its defence.

Former US President Joe Biden repeatedly said Washington would come to Taiwan’s aid if China attacked; current leader Donald Trump has been more circumspect.

“I don’t trust Trump’s words because he cuts down all the migrants,” said Ivy Centena, 52, a Filipina working in a motor vehicle parts factory in Taoyuan. “I don’t think he would defend Taiwan. He’s only words, not doing. I don’t trust him.”

Centena’s views align with a broader sentiment, reflected in an “American Portrait Survey” conducted in March. The results were released in May by a research fellow at Academia Sinica’s Institute of Political Science.

The poll, which drew on interviews with more than 1,200 adults in Taiwan, showed 18.7 per cent saying the US “definitely would not” intervene if mainland troops attacked the island and 23.7 per cent saying it was “unlikely”.

Those numbers came in at 15.3 per cent and 16.4 per cent, respectively, in the survey’s 2024 edition.

Analysts said China may factor foreign workers into any attack plan given the likely political fallout of mass casualties involving the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, a region it actively courts.

“The last thing China wants to do is attack Taiwan and kill 1 million Aseans,” said Richard Heydarian, professorial geopolitics chair at Polytechnic University of the Philippines. “That will be part of the game.”

But Beijing has also played it both ways, he added. “The Chinese ambassador here said, ‘You have a great Filipino community in Taiwan. It would be a shame if something happened to it,’” Heydarian said.

“Even humanitarianism will be weaponised … It’s a very complicated situation.”

Another scenario would see China interfere in the rescue process. “Beijing could claim that it represents Taiwan and force the Southeast Asian governments to negotiate with [the mainland] instead to ensure peaceful repatriation of their citizens,” said Shen, the Eurasia Group analyst.

Taipei has reportedly held conversations with Asean countries about rescue operations. “There may be some ideas but no formal discussions,” said a Taiwanese diplomat, who added that countries would likely liaise with Taiwan’s foreign and defence ministries as conditions worsened – if they had time.

Taiwan’s September 2024 “Whole-of-Society Defence Resilience” initiative does not include guest workers.

In the Taiwanese TV show Zero Day, a speculative depiction of a mainland attack, a Vietnamese worker emerges from her job at a karaoke bar saying: “My government has dispatched a boat to take us home.”

But self-defence civic groups in Taiwan say the unique vulnerabilities of migrant workers are rarely factored into Taipei’s plans.

“We’ve been kicking the idea around, including working with foreign migrant governments,” said an official with Kuma Academy, which trains Taiwan residents for emergencies.

“They should be provided for regardless of nationality.”

Migrants are keenly aware of their precarious position. “We come here to work, not for the war,” said factory worker Centena, who has not seen her Philippines-based husband or two sons since 2019.

“If it comes to war, maybe we will wait for our employer to say, ‘We cannot protect you,’ and we’ll go home.”

Beijing’s long-standing intimidation manoeuvres intensified after the pro-independence ruling party won a third term last year.

Five months ago, following a speech by Taiwanese leader Lai Ching-te, some 31 People’s Liberation Army warplanes crossed the median line under Strait Thunder 2025A exercises during a 24-hour period, Taiwan’s Defence Ministry reported, with two maritime formations observed in the island’s northern and central waters.

Any attack would create international shock waves given adjacent global shipping lanes and Taiwan’s critical semiconductor industry, risking up to US$3 trillion, including Group of Seven sanctions, the Rhodium Group and Atlantic Council estimated in 2023.

In August, ex-military personnel, academics and security experts held a closed-door exercise in Singapore to game out scenarios were 1 million Asean workers stranded by a China blockade.

The reported outcome saw rescue only possible after Singapore convinced Beijing to allow an evacuation.

The London-based International Institute for Strategic Studies, which organised the exercise, did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

For migrant workers in Taiwan, an attack is concerning. But it is also not seen as imminent – and something they have little control over – as they worry about daily life.

Centena contrasts the seemingly nonchalant attitude of many Taiwanese with that of the Philippines, which has repeatedly pushed back on Beijing’s expansive South China Sea claims.

“In the Philippines, the strength is very high. But here in Taiwan, no issues, they are quiet, the government is quiet,” she said. “Maybe they don’t want to provoke or show what’s happening.”

Centena added that it is hard to know which approach works better. “If you show them that you are not afraid and you want to fight for your rights, they just bully you. If you show them that you will fight, maybe they will stop bullying you,” she said. “But you need to stand up for your rights.”

Banugan, the housekeeper who is a board member at the worker rights group Migrante, sends some NT$11,000 a month (US$362), or around half her salary, to the Philippines each month to support her father, son and niece.

For her, cross-Strait tension goes beyond a possible evacuation.

“Rescuing migrant workers is not the solution. For us, they should have a better economy in the Philippines so we don’t have to work overseas,” said Banugan. “If they prioritised industrialisation and good salaries, no one would be forced to work abroad.”

“They are using migrant workers to be the front line in the war,” she added. “They are just putting us in the danger line.”

Additional reporting by Robert Delaney