By Holly Mead

Copyright independent

Experts will tell you not to look at your investment portfolio too often – after all, investing is for the long-term, and checking in too regularly can mean you get spooked by short-term dips in the market. But that doesn’t mean you should ignore it completely.

Rebalancing your portfolio is an important part of good investing hygiene. It requires checking in once or twice a year and doing some tinkering to ensure your investments are behaving as you had intended.

For example, your money was equally split between two funds: after a year, one is up 50% and the other has fallen 50%. Your portfolio is now no longer split 50/50 between the two. Instead, the better performer now accounts for 75% of your assets and the underperformer just 25%.

This is a problem as it changes the risk profile of your portfolio. If the underperformer starts to recover, you won’t benefit as much, and if the outperformer starts to dip, you will be more exposed to losses.

So, what should you do? Here are five rules for rebalancing.

What’s happened since you last logged in? A lot can change in markets, and often very quickly. Do some reading about global markets and understand how they have impacted your portfolio. This will help you decide what to do next.

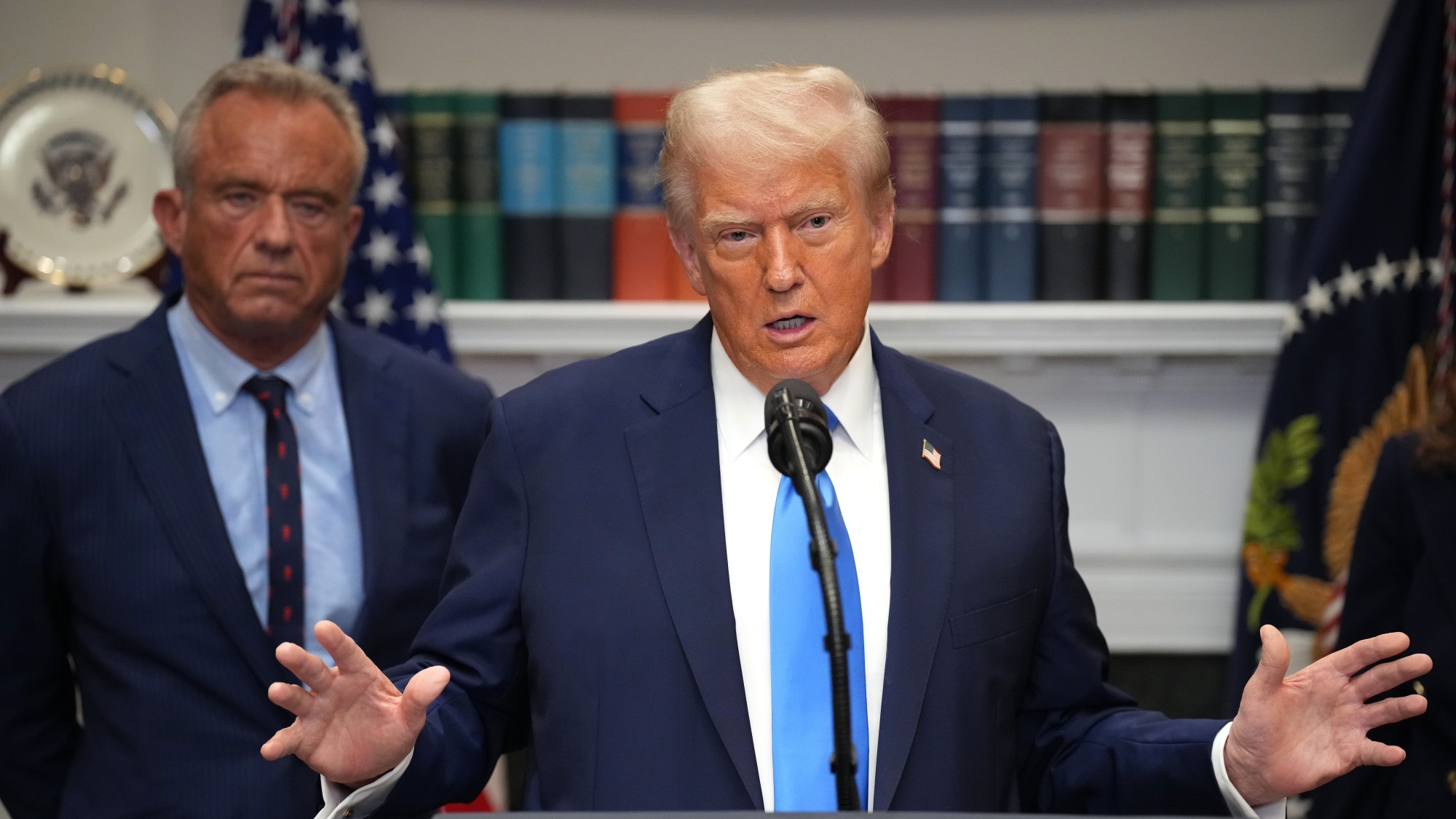

Time it right. The right time to rebalance a portfolio is not during a major market event, such as the stock market falls seen in April around Donald Trump’s trade tariff announcements.

“Rebalancing on the noisiest days is a bit like trying to install seatbelts during a car crash – there is a chance it will help, but you would have been much better off putting them on in the first place,” says Ben Gilbert, portfolio manager at Sarasin & Partners. “Once the initial panic passes, you will find better prices and a calmer environment, allowing you to rebalance at a time that reduces your risk of getting it seriously wrong.”

Paul Derrien, from Canaccord Wealth, recommends setting rules around when to rebalance to avoid making knee-jerk reactions or emotional decisions.

You could, for example, do it whenever a holding’s allocation in your portfolio moves by 10% either up or down – so if you had originally set it to account for 20% of your assets and it moves to 30% or 10%.

Do you still believe in all your holdings?

Consider their performance against similar investments, read the fund factsheet to check how it is invested or check the company’s latest results, and read the fund manager’s latest commentary to understand how they are thinking about the market.

If the manager of a fund has changed, you might consider selling if the successor’s strategy is different or their track record not as strong, says Darius McDermott, managing director at FundCalibre.

Rob Morgan, chief investment analyst at Charles Stanley, adds: “There is no point in rebalancing in something you have lost faith in. Make sure you are still happy with each of the components in your portfolio.”

Do your holdings still fit your investment goals? The appropriate level of risk for you will change over time, depending on your life stage, health, wealth and income needs.

That means the investments you chose ten years ago may no longer be suitable.

Don’t just consider individual holdings – look at your overall exposure to different asset classes (such as equities, bonds or property), geographical regions, and market caps (for example, small or large companies).

If your portfolio has seen quite dramatic performance – either up or down – it could be a sign you need to diversify more. Spreading your money across different types of investment should mean a steadier journey as they are unlikely to all rise and fall at the same time.

Consider broadening into different assets or using a very broad, multi-asset fund at the core of your portfolio, says Morgan.

Once you’ve worked out what you need to do to get your portfolio back in shape, it’s time to start trading.

Rebalancing simply means trimming the holdings that have grown and reinvesting the money into those that have not been as strong. Alternatively, if you are still building up your portfolio, you could just gradually add any new contributions to the laggards.

“If things have not shifted too much, you may not need to do anything. But if there are big differences between the top performers and the laggards, you should consider acting,” says Morgan.

Don’t let any one investment dominate your portfolio. It can be tempting to add to top performers, but this could mean you end up over-exposed to “hot” areas of the market, which could hurt when they fall out of favour, McDermott explains.

“If a holding is too small to move the needle – say, it accounts for less than 1% of your portfolio – either build the position into something meaningful or cut it out entirely,” he adds.

Once you are happy with your portfolio, log out and try not to check in again too soon.

It’s easy to feel like you should be doing something – especially if the market is volatile – but it is important not to make changes too regularly.

There are costs each time you buy and sell a holding which could eat into your returns in the long run.

McDermott says: “If you’ve built a diversified portfolio aligned to your risk profile, you shouldn’t need to tinker constantly. But, just like a car, it’s sensible to give your investments an MOT every six to twelve months to make sure everything is still fit for purpose.”

When investing, your capital is at risk and you may get back less than invested. Past performance doesn’t guarantee future results.