By Hiroshi Yamamoto

Copyright kyodonews

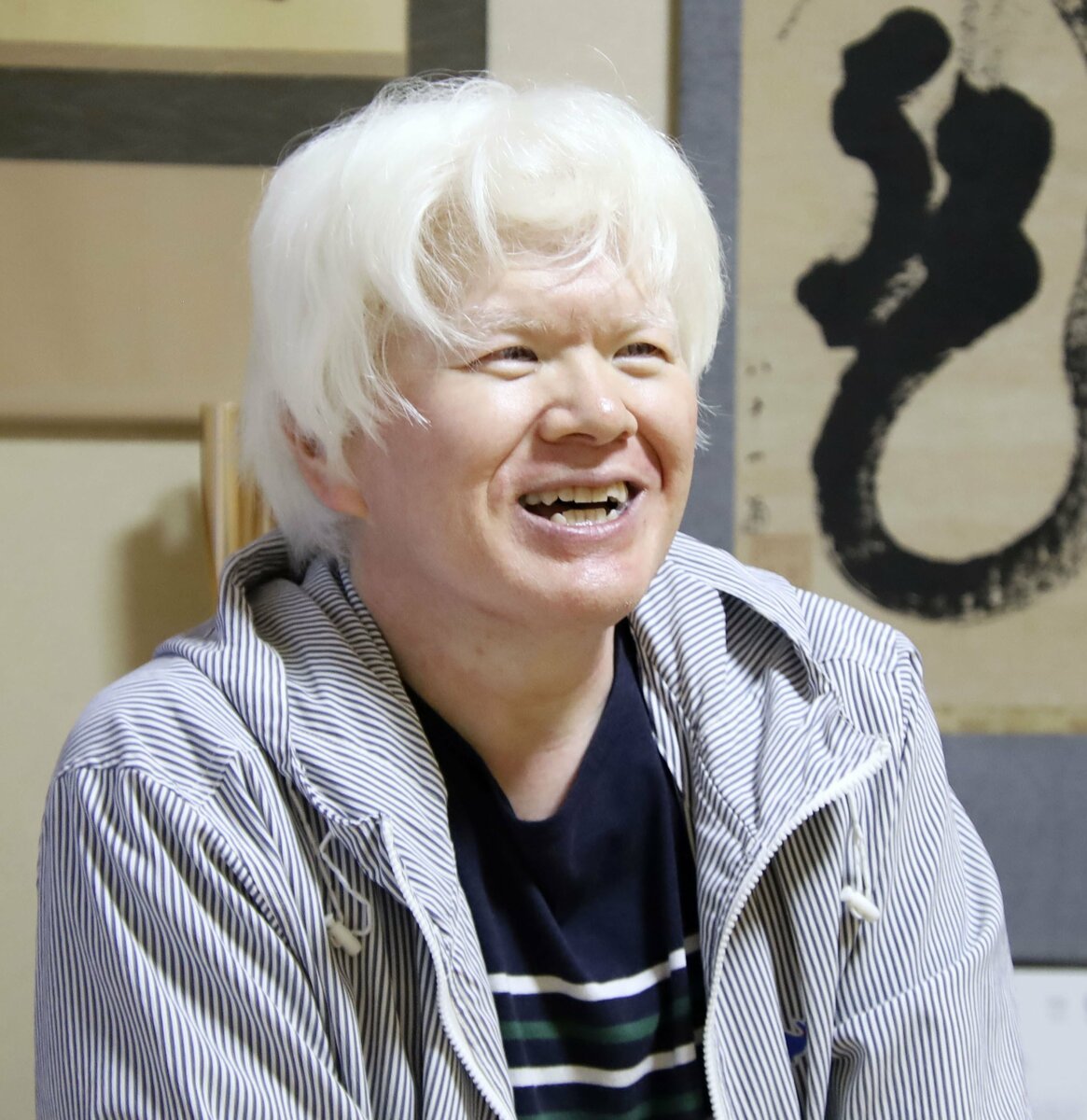

CHIBA, Japan – Born with white hair, pale skin and failing eyesight, Nobuyuki Ishii spent almost 30 years not knowing why he was different.

Today, the 52-year-old from Chiba Prefecture has transformed that painful time into a mission: helping others with albinism live with strength and dignity.

For more than two decades, Ishii has traveled across Japan at his own expense, meeting people with the rare genetic condition that prevents the body from producing melanin, the pigment that gives color to the skin, hair and eyes.

In Japan, the incidence of albinism is about one in 20,000, meaning there are roughly 6,000 people with the condition, according to the Japan Albinism Network.

In Japan and other countries, harmful misconceptions have persisted, including beliefs that people with albinism have shorter lifespans, have magical powers or may die if exposed to the sun.

Ishii has spoken in person with more than 1,000 individuals, listening to their struggles and offering support.

“I think I’m the person with albinism who’s met the most people like me in Japan,” Ishii says with a laugh.

His determination comes from a childhood filled with uncertainty. In elementary school, classmates would ask, “Why are you white? You’re an alien. Gross!”

Doctors told him his poor eyesight could not be cured, but nobody explained why. For years he believed frightening rumors, such as that people like him would die prematurely.

It was not until he was formally diagnosed at 26 that he finally understood. The revelation lifted years of confusion.

“My white hair and skin are all mine,” he recalls thinking. That sense of acceptance became the spark for his life’s work.

In the late 1990s, Ishii launched a website under his real name and photo, an unusual move at the time, to spread accurate information. He endured slander and abuse but pressed on, convinced that visibility would empower others.

The parents of a person with albinism once feared for the future, telling him, “We’ll die with my son.” By showing them assistive devices for low vision and sharing stories from others, he convinced them that life could be lived fully regardless of the condition.

By 2003 he had organized the first social gathering for people with albinism in Chiba, near Tokyo, an effort that soon expanded nationwide. Since then, his work has stretched from small one-on-one meetings to books and lectures.

In 2017, he published “Let’s Talk About Albinos,” a compilation of the views of albinism patients and doctors. It won the Medical Journalists Association of Japan award for excellence.

In 2021, he carried the Olympic torch in Tokyo, calling it a chance “to spread understanding about albinism to the world on this coveted stage that inspires people, regardless of country, religion, or race.”

Ishii’s efforts have helped shift the needle. Where once many hid their condition, today people with albinism increasingly post online using their real names and photos.

Advocacy groups also credit Ishii with creating a network of trust. One in the Kansai area describes him as a source of security for families, praising his wealth of knowledge and empathy.

Despite worsening eyesight — he is now almost completely blind in his left eye — Ishii continues to travel on weekends while holding a day job at a chemical factory. His message remains consistent: people with albinism must practice acceptance, connection, and resilience.

“Correct information is spreading, and we’re getting closer to the ideal society we envision,” he says. “I want to help not only people with albinism, but anyone who finds life difficult.”