Copyright dailymail

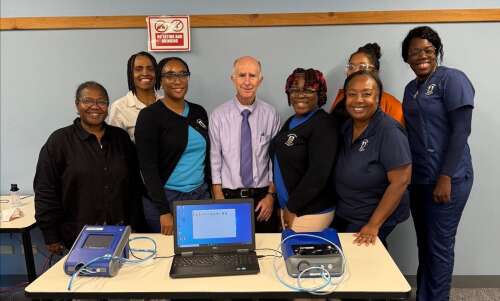

Everyday chemical now linked to liver disease and cancer, study suggests READ MORE: Dry-cleaning chemical may be fueling rise in Parkinson's disease By CASSIDY MORRISON, US SENIOR HEALTH REPORTER Published: 20:28 GMT, 6 November 2025 | Updated: 20:34 GMT, 6 November 2025 Scientists have identified a typical household and dry cleaning ingredient as a new risk factor for severe, potentially fatal liver damage. The compound tetrachloroethylene (PCE), commonly used in dry cleaning and present in everyday products like craft adhesives, stain removers and stainless steel polish, is a potential threat to liver health, according to the latest research from Keck Medicine of the University of Southern California. Researchers measured PCE levels in the blood of more than 1,600 adults aged 20 and older. They found that approximately seven percent of this population had detectable amounts of the chemical. People are exposed to the chemical when it evaporates into the air and inhale it. People with any detectable level of PCE in their blood had a three-fold higher risk of developing liver fibrosis marked by a buildup of scar tissue that can progress to liver cancer, liver failure or even death. PCE is the primary solvent used in many dry-cleaning machines and workers breathe in this contaminated air all day, leading to high, chronic exposure. When the customer brings their clothes home, they are exposing themselves to low levels of PCE, which can remain in the fabrics of the clothing and within the plastic wrapping for days, leeching toxins into the air of their home, car or closet. The researchers also determined that the more a person was exposed, such as over decades of working in dry cleaning or using the service, the more likely they were to experience life-threatening liver damage. This study, for the first time, points to a potential environmental cause. The chemical has been designated a probable carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer, with links to bladder cancer, multiple myeloma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. An estimated 80 to 100 million adults in the US may have liver disease, a silent killer, and are unaware of it. The liver often remains silent even when diseased (stock) Scientists used data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) from 2017 to 2020 to study a large, representative sample of American adults. They identified people with significant liver scarring, or fibrosis, using an ultrasound test that measured liver stiffness. Then, they analyzed whether people with a specific chemical (PCE) in their system were more likely to have this liver scarring. Skin condition suffered by millions could be sign of deadly liver disease Of the more than 1,600 American adults tested, 7.4 percent had detectable levels of PCE in their systems. Those with any trace of PCE in their blood were over three times more likely to have significant liver scarring. The results further showed a clear dose-response relationship, where the higher the concentration of PCE in a person's body, the greater their risk became. Dr Brian P Lee, a liver transplant specialist with Keck Medicine and lead author of the study, said: ‘Patients will ask, how can I have liver disease if I don’t drink and I don’t have any of the health conditions typically associated with liver disease, and the answer may be PCE exposure.’ Notably, the link between PCE and liver scarring held strong even after accounting for other common causes like alcohol use and obesity-related fatty liver disease. For every single-unit increase of PCE, the risk of liver scarring skyrocketed more than fivefold, indicating a direct escalation of risk with exposure. The presence of PCE was associated with a significant 27.7 percent increase in the actual number of liver disease cases. The graph shows that hospital visits for liver conditions almost uniformly increased from 2018 through 2022. Liver disease due to alcohol abuse increased most sharply, followed by cirrhosis and liver scarring Liver disease is a silent and underdiagnosed epidemic in the US. While only about 4.5 million adults have a formal diagnosis, experts estimate that as many as 100 million people, or one in three adults, are living with fatty liver disease, often without any symptoms or knowledge of their condition. Liver disease is most often linked to heavy alcohol use, fat buildup in the liver associated with obesity, diabetes and high cholesterol, or infection with hepatitis B or C. Lee said: ‘This study, the first to examine the association between PCE levels in humans and significant liver fibrosis, underscores the underreported role environmental factors may play in liver health. ‘The findings suggest that exposure to PCE may be the reason why one person develops liver disease while someone with the exact same health and demographic profile does not.’ Surprisingly, people’s health risks did not follow the standard pattern of poverty. Researchers noted that the people with the highest levels of PCE in their systems tended to be wealthier and more affluent than those with lower levels, ‘attributing this to participants with higher incomes being more likely to utilize dry-cleaning services, resulting in higher exposures.’ ‘However, people who work in dry cleaning facilities may also face elevated risk due to prolonged, direct exposure to PCE at work,’ Lee added. PCE cannot be smelled, seen or tasted. For most people, the primary route of exposure is through the nose. PCE evaporates easily into the air, and inhaling its vapors is a direct path into the bloodstream. This can happen in obvious scenarios, like living in an apartment above a dry cleaner, but also in more subtle ways, like bringing home freshly dry-cleaned clothes that still carry the chemical’s invisible residue. PCE is also a persistent contaminant that can leach into drinking water from polluted soil and groundwater, especially near industrial sites or waste disposal areas. While less common today, some consumer products like certain paint strippers, adhesives and spot removers have also historically contained PCE, offering a direct path of exposure through the skin or lungs during use. PCE is not only toxic to the liver on its own. The body's attempt to get rid of it creates another harmful chemical called TCA that interferes with the core functioning of liver cells, including how the body handles fats and sugar. PCE can also be processed by latching onto a protective substance in the body called glutathione. However, this process creates other byproducts that are just as toxic to the liver and kidneys. Lee said his team’s research is the starting point for a deeper investigation into the environmental factors at play. He said: ‘We hope our research will help both the public and physicians understand the connection between PCE exposure and significant liver fibrosis. ‘If more people with PCE exposure are screened for liver fibrosis, the disease can be caught earlier and patients may have a better chance of recovering their liver function.’ His team's findings were published in the journal Liver International. Share or comment on this article: Everyday chemical now linked to liver disease and cancer, study suggests Add comment