By Sebastian Contin Trillo-Figueroa

Copyright scmp

Europe’s attempt to reduce its dependence on China through trade agreements in Asia may not achieve the intended outcome. Instead of breaking ties, Brussels is being drawn deeper into supply chains where Chinese companies remain central.

EU deals in recent years with Vietnam, Indonesia and India broaden market access and diversify suppliers, yet also channel European demand into production networks controlled by China. Meanwhile, the European Union continues trade talks with Thailand, Malaysia and the Philippines. The result won’t be liberation from Beijing, but reliance restructured into more complex forms.

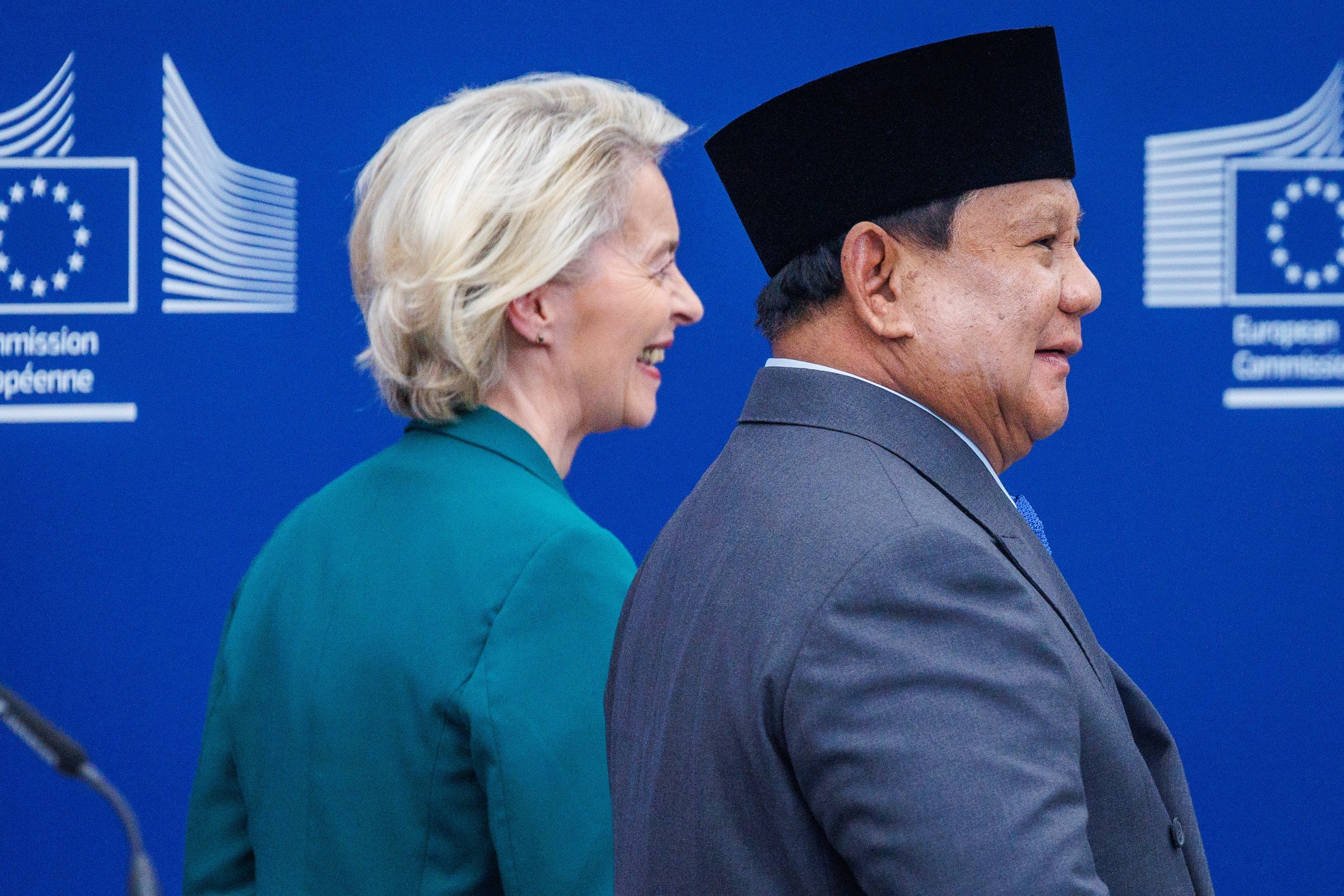

Last week, Jakarta and Brussels concluded a comprehensive economic partnership agreement (CEPA) after nearly a decade of negotiations, profiting more than 700 million consumers through tariff elimination. Hailed as a breakthrough in supply expansion, the CEPA broadens the EU’s access to Indonesia’s nickel, palm oil and digital services; yet its deeper implications are multifaceted.

Indonesia possesses the world’s largest nickel reserves, essential for Europe’s energy transition. But 75 per cent of its nickel refining capacity is controlled by Chinese stakeholders. So European industries gain access to raw materials, but via a value chain shaped by Beijing’s presence.

In manufacturing and digital services, the imbalance persists. Indonesia’s semiconductor ambitions depend on Chinese components and South Korean and Taiwanese inputs, while its digital market integrates Europe into platforms controlled by Beijing.

Palm oil reinforces the trend. The CEPA is expected to increase Indonesian palm oil exports to the EU to about four million tonnes next year, up from an estimated 3.3 million tonnes this year, lowering costs for industry yet boosting Chinese agribusiness conglomerates with major stakes in the plantations.

Vietnam also illustrates the trap of indirect dependence. The EU-Vietnam free trade agreement, ratified in 2020, promised to ease reliance on Chinese manufacturing, yet up to 67 per cent of Vietnam’s fabric imports come from China and its electronics assembly relies on components sourced from across the border.

India offers a similar picture. Its pharmaceutical sector is a major supplier of generics and active ingredients to Europe, but an estimated 70 per cent of the raw chemicals and key starting materials come from China. As much as half of India’s electronic component imports come from China.

Hence, in sourcing Indonesian, Vietnamese or Indian products, Europe does not escape Chinese influence. Rather, it channels demand into supply chains where Chinese companies hold decisive positions, relying on intermediaries Beijing controls. It seems China is positioned to benefit regardless of the direction of European trade flows.

Furthermore, the geopolitical effect for Europe is negligible. Any decision by China to restrict rare earths, semiconductor inputs or key chemicals would reverberate across the Asia-Pacific, disrupting European supply lines despite the diversification efforts.

Expanding trade ties broadens Europe’s network of partners but multiplies the channels through which Beijing can exert leverage, increases Europe’s exposure to Chinese-controlled value chains through third-party pressure points, and underpins Beijing’s centrality in global strategic industries.

The economic data highlights these vulnerabilities. For instance, EU exporters can expect to save €600 million (US$704 million) annually from the CEPA with Indonesia, while Germany’s car exports to China alone were worth US$16.2 billion in 2023. If Beijing were to restrict Europe’s market access, the loss from car exports alone would vastly outweigh trade savings elsewhere.

Still, dismissing diversification as meaningless misses its institutional dimension. These agreements give Brussels a stronger presence in Asia-Pacific economies and cement sustainability, labour and digital governance standards, though unevenly enforced – as proved by the repeated deferral of the EU anti-deforestation regulation.

The agreements also expand options for partner governments. Indonesia is reducing its reliance on Chinese and American capital by increasing Europe’s role within its circle of trade partners. Vietnam integrates its EU deal into a broader circumventing strategy. India treats European investment as a complement to other partnerships. The EU’s diversification is also helping others to diversify.

This produces a layered interdependence: Chinese companies dominate inputs and infrastructure in Asian production while Europe provides some hedging. Brussels cannot escape Chinese influence, yet its agreements create bargaining power and open up market access. Full autonomy remains out of reach, but diversification reveals an institutional and economic weight rather than mere cosmetic change.

China’s reach still guides regional trade and geopolitics. Export-dependent governments calibrate foreign policy primarily around Beijing’s preferences. Indonesia’s positions on South China Sea disputes reflect Chinese stakes in its nickel, while Vietnam’s cautious stance on Taiwan stems from its reliance on Chinese-controlled supply chains. By structuring access to capital, technology and production networks, China embeds leverage into the very systems Europe seeks to engage.

Europe’s Asian trade policy thus delivers mixed outcomes. It reduces some reliance on China while extending indirect exposure through intermediaries. Beijing’s leverage persists but diffuses across multiple economies. Europe gains presence and institutional ties, but not the independence its leaders proclaim. The outcome is deeper access to markets embedded in production systems that China continues to underpin.

The first objective should be to manage this duality. Agreements extend Brussels’ scope but also entrench Beijing’s role. These dynamics suggest China-EU relations will increasingly be defined not by direct confrontation but by China’s ability to maintain leverage through regional intermediaries, making European independence illusory.

The second goal may be not to eliminate dependence but to stimulate interdependence: embedding standards, securing supply and diversifying partners while acknowledging China’s dominance. In any case, the deals position Europe inside the supply chains where global power is increasingly determined.