Copyright STAT

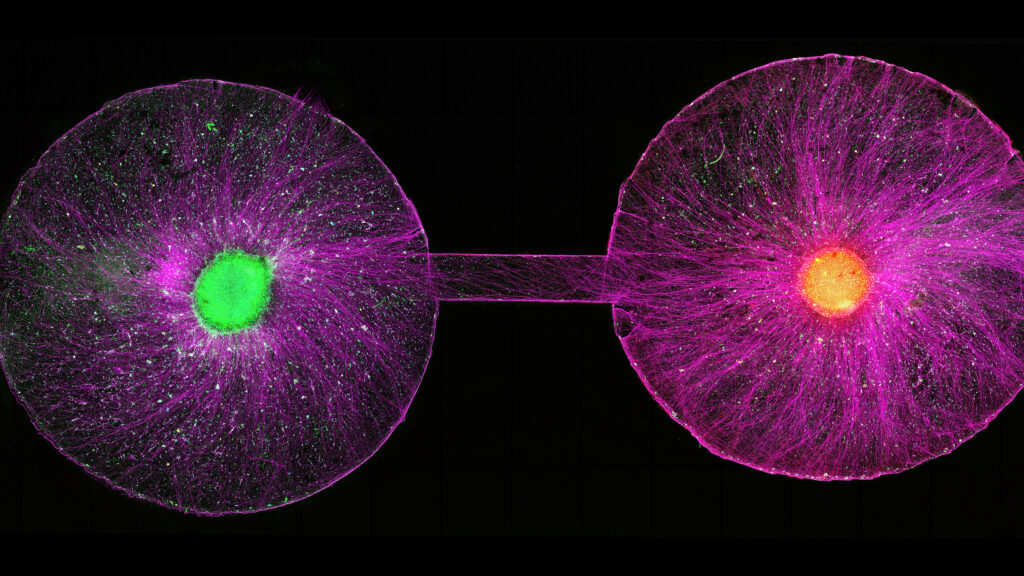

It’s been just over a decade since the first human neural organoids sparked into existence. Even back in 2013, when these clumps of cells in a dish could do little more than self-organize and spike their calcium levels in response to an electric signal, they ignited an intense ethical debate, including about whether they can suffer or be conscious, and whether they have human rights. Since then, these lab-created, three-dimensional structures made from human stem cells have shown remarkable capacity for mimicking key aspects of normal brain function, as well as severe psychiatric and neurological diseases including schizophrenia, autism, and Alzheimer’s. As researchers have coaxed them into increasing levels of complexity — growing them for years in some cases, or linking together miniature versions of different brain regions — they’ve helped reveal what goes wrong in the brains of people suffering from such diseases and offered a powerful new type of testing ground for experimental treatments. Advertisement Such breakthroughs have also raised new and more urgent ethical concerns about the organoids themselves, but also about the rights of people who donate the cells that serve as their foundation and the animals that wind up with them melded into their own minds. In an effort to address these ethical grey areas, 17 leading scientists and bioethicists from five countries are urging the establishment of an international oversight body to monitor advances in the rapidly expanding field of human neural organoids and to provide ethical and policy guidance as the science continues to evolve. The call to action, published Thursday in Science, comes as U.S. government agencies are making new investments in organoid science aimed at accelerating drug discovery and reducing reliance on animal models of disease. In September, the National Institutes of Health announced $87 million in initial contracts to establish a new center dedicated to standardizing organoid research. The move followed an earlier pledge by both the NIH and the Food and Drug Administration to reduce, and possibly replace, testing on mice, primates, and other animals with other methods — including organoids and organ-on-a-chip technologies — for developing certain medicines. Advertisement Government promotion of human stem cell models more broadly will only increase the recruitment of new researchers into the field of neural organoids, which has seen an explosion from a few dozen labs a decade ago to hundreds around the world now, said Sergiu Pasca, a pioneering neuroscientist and stem cell biologist at Stanford University who co-authored the Science commentary. “As the field is expanding and moving faster, there are a number of potential ethical issues arising down the line that make it necessary to start a conversation now,” Pasca said. “We can make many of the cells in the nervous system now, and we can keep them for longer, for years in a dish, and we can connect them with each other in more and more meaningful ways. It’s not necessarily that there is a specific experiment that is concerning, but the progress that is being made and the fact that this is done with human cells requires that we give special attention to this topic.” In 2017, Pasca’s group published a study which used human stem cells donated by three patients diagnosed with Timothy syndrome — a rare, severe form of autism — to create miniature versions of specific regions of the brain. In watching them develop, they noticed that neurons from the deep brain layer had trouble migrating into the right places in adjoining layers. These neurons contained abnormally high levels of instructions for making calcium ion channels, making them barrel forward haphazardly. The insight allowed the research team to develop an antisense oligonucleotide treatment that could silence the instructions that made the neurons too jumpy. Last year, they showed this approach could restore normal cell movements during brain development. Moves toward a clinical trial are now underway, Pasca said, with hopes to launch sometime next year. His lab’s work is a bright spot in the field of medical applications of neural organoids — highlighting their potential to reveal aspects of human biology long hidden by layers of bone and tightly packed cells and blood vessels and open up new therapeutic avenues for treating psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders. Advertisement But it also underscores some of the field’s emerging ethical issues.The experiments involved transplanting human organoids into the brains of baby mice and allowing them to integrate into the developing animals’ circuits. While there are laws and standards that govern how animal welfare needs to be considered by ethics bodies approving such experiments, assessing how human neural organoids might be changing animals’ abilities, and even giving them new capabilities, falls outside the remit of existing review structures. “What does it mean if human cells are causing gains in animals’ abilities?” said Insoo Hyun, a bioethicist at Harvard Medical School and a co-author of the Science commentary. “Currently, we’re not set up to deal with that.” These concerns ratchet up as researchers look to move from experiments with living rodents to non-human primates. Bigger brains, bigger clumps of human brain-like materials, and bigger amounts of integration all add to the potential that something unexpected might emerge. Spelling out what to look for, and how, in advance of such experiments is something that should be a priority for existing standard-setting bodies like the International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR) or the International Neuroethics Society (INS), Hyun said, especially because outside of animal cruelty laws, there are no legal limits on neural organoid use anywhere in the world. The ethical issues he and his colleagues outlined include questions about whether these lab-cultured constructs could one day become sentient, feeling sensations like pain, or even achieve something akin to consciousness. Neither seems remotely possible today, but the science of how these phenomena develop is still murky enough that it’s unclear how one would tell if such thresholds were being crossed. Because of that, and because of the rapid pace of progress, there are also questions about how specific the consent process needs to be for stem cell donors. Even if they might be okay with having their cells turned into organoids, how would they feel having those organoids implanted into the brain of an animal? Or infected with a potential bioweapon? Or plugged into a biocomputer? “Wetware computing is one of the rapid new directions for this field that we’re just starting to grapple with,” Hyun said. Advertisement Keeping tabs on the field as it expands geographically and across disciplines is something he and his co-authors would like to see tackled either by existing organizations, like ISSCR and the INS, or by a new group with dedicated, sustained funding. Its focus should be on producing regular reports on recent developments that merit additional ethical review and creating spaces for scientists and the general public to convene to discuss whether and how responsible organoid research might progress. While the field may recognize the need for such an effort, it remains an open question who is willing to take it on and commit the funds necessary for its creation and long-term operation. In the short-term, at least, Stanford and the neuroscience-focused philanthropy the Dana Foundation are supporting an effort to get the wider conversation going. Next week, hundreds of the field’s brightest luminaries, along with bioethicists, legal scholars, policymakers, and patient advocates, will gather at the historic Asilomar conference grounds in California for a three-day discussion of the ethical, legal, and societal dimensions of neural organoid research. It’s being organized by Pasca and Hank Greely, director of the Stanford Center for Law and the Biosciences, and its location is no accident. It’s the same place where, 50 years ago, the now-late David Baltimore led a conference on recombinant DNA, which successfully fended off calls for a moratorium on the technology and ultimately led to its oversight by the NIH. That conference also spawned federal and foreign biosafety regulations that banned some uses — like reproductive cloning — while allowing others to flourish and fuel the growth of the entire biotechnology sector. To many, it’s the definitive story of modern scientific self-regulation. It’s a story Pasca is hoping to rewrite with neural organoids. “We’re not saying there’s necessarily the same kind of urgency as there was at that time,” Pasca said. “Experiments are progressing, but it’s not like something like CRISPR that you can do within days with minimal equipment. There’s quite a lot of expertise needed for building very complicated assembloids and it takes a long time. But what we are trying to do is predict what the issues will be down the line, right? That’s what you want to do for a field is, you want to think about what are the ethical and societal implications before they become issues.” Advertisement