Copyright mwnation

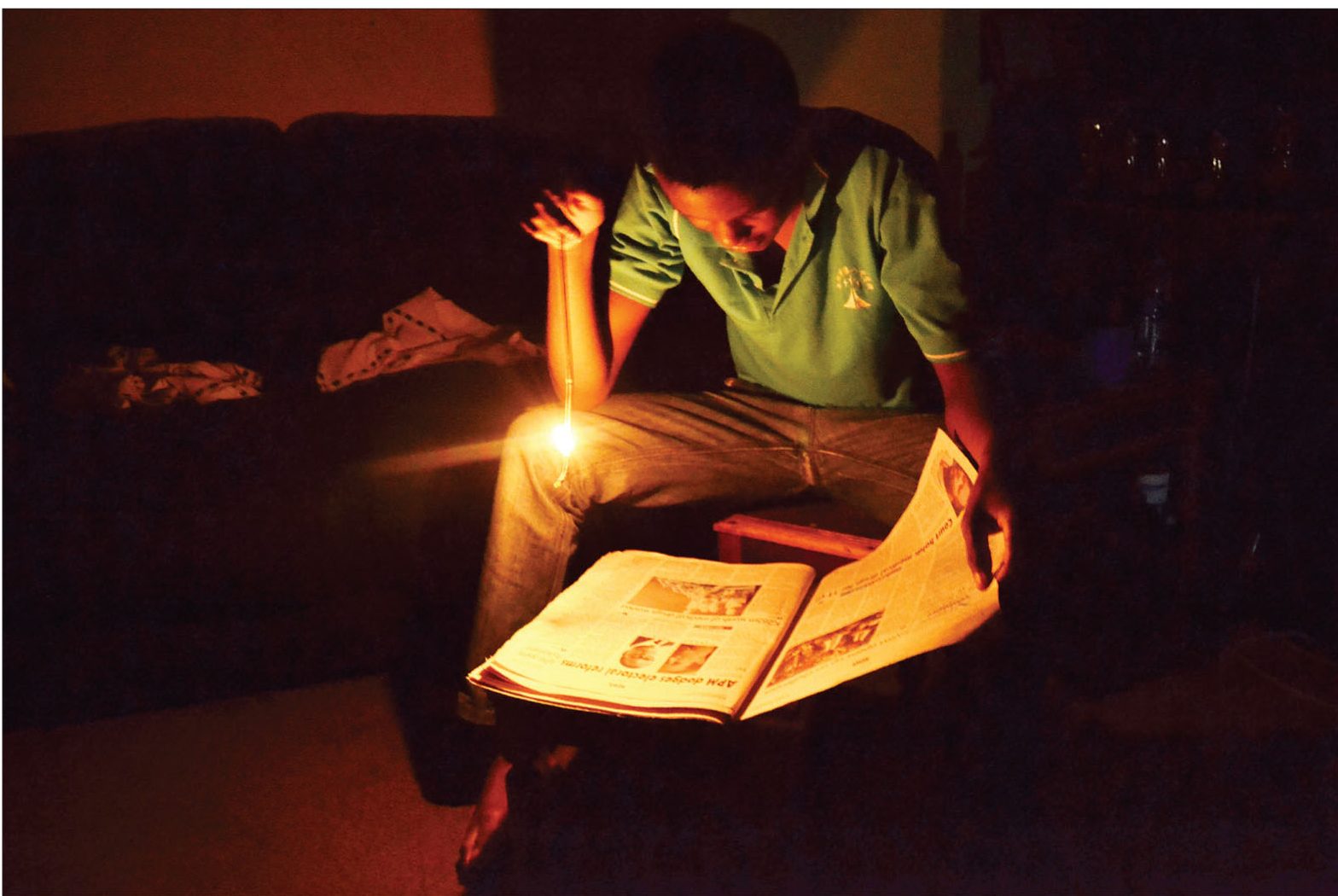

Greetings from the Munda wa Chitedze Farm where I relocated from the hustle and bustle of your city. Unlike you in that concrete jungle, we do not suffer in peace at the farm. The chitedze crop in the garden is yellowing early this year. Not for lack of rain, but because the irrigation pump has been sulking again—no power. Escom, our beloved electricity supplier, has once more left us in the dark. And not just metaphorically. I remember the day they said Escom would be unbundled. It was 2017, and the air was thick with reformist optimism. The idea was simple: break up the monolith, make it leaner, more efficient, and attractive to private investors. Generation would go to Egenco, market operations to Power Market Limited (PML), and Escom would stick to transmission and distribution. It sounded like a recipe for progress. But like a recipe missing salt, the taste has been off ever since. Let’s start with the money—or lack thereof. Escom hasn’t made a profit since the unbundling. The last time it did, we were still debating whether WhatsApp was better than SMS. Now, Escom buys electricity at a higher price than it sells it. It’s like buying tomatoes at K500 a kilo and selling them at K300, hoping volume will save you. The revenue streams have become as fragmented as a broken clay pot. With generation now under Egenco, Escom is left juggling bills with fewer coins in the purse. It’s a bit like being the eldest child in a family where the younger siblings have taken over the kitchen and the budget, but you’re still expected to feed everyone. Operat iona l ly, t h ings haven’t fared much better. The billing system is now a maze. Procurement delays have become the norm, and infrastructure upgrades are slower than a bicycle on a muddy road. Dear Diary, without direct control over generation, Escom is often left waiting for power like a farmer like me waiting for rain—hopeful, but helpless. The synergy that once existed between generation, transmission, and distribution has evaporated. Planning is no longer integrated. It’s like trying to plough a field with three oxen pulling in different directions. You end up with furrows that confuse even the crows. Then there’s coordination. With Escom and Egenco both doing their own thing, oversight has become bureaucratic and, some say, politically influenced. Civil society groups have raised concerns about sabotage and policy confusion. The reforms were meant to attract Independent Power Producers (IPPs), but progress has been slower than a tortoise with a limp. And yet, the intentions were noble. Escom’s old structure made it hard to pinpoint inefficiencies. Unbundling was supposed to streamline operations, improve transparency, and bring in fresh investment. It was meant to align us with global best practices. Kenya did it. Ghana did it. South Africa is doing it. Why not us? What works elsewhere, doesn’t seem to work here. In Kenya, they split the power sector into KenGen (generation), Ketraco (transmission), and Kenya Power (distribution). The result? Improved grid reliability and a surge in IPPs. Ghana followed suit with Volta River Authority, GRIDCo, and ECG. Transparency improved, and investors came knocking. But in Malawi, the story reads differently. Our unbundling created overlapping mandates and weakened coordination. Escom’s pricing model is unsustainable, and the hoped-for IPPs are still circling, unsure whether to land. So, what can be done? For starters, we need to clarify roles. Escom, Egenco, and PML must know who does what, when, and how. Reg u l at i on mu st b e strengthened. Mera, our energy regulator, should be empowered to enforce standards and pricing mechanisms. Licensing and procurement processes must be streamlined to attract private sector participation. And governance must improve—less politics, more professionalism. You see, seconding CEO Kamkwamba Kumwenda to teach at the Malawi University of Business and Applied Sciences is not the solution to the prolonged blackouts we are facing daily. Dear Diary, we have learnt to keep candles handy. The irrigation pump may sulk, but the chitedze still needs tending. We can’t use the diesel pump, because that is another long story!