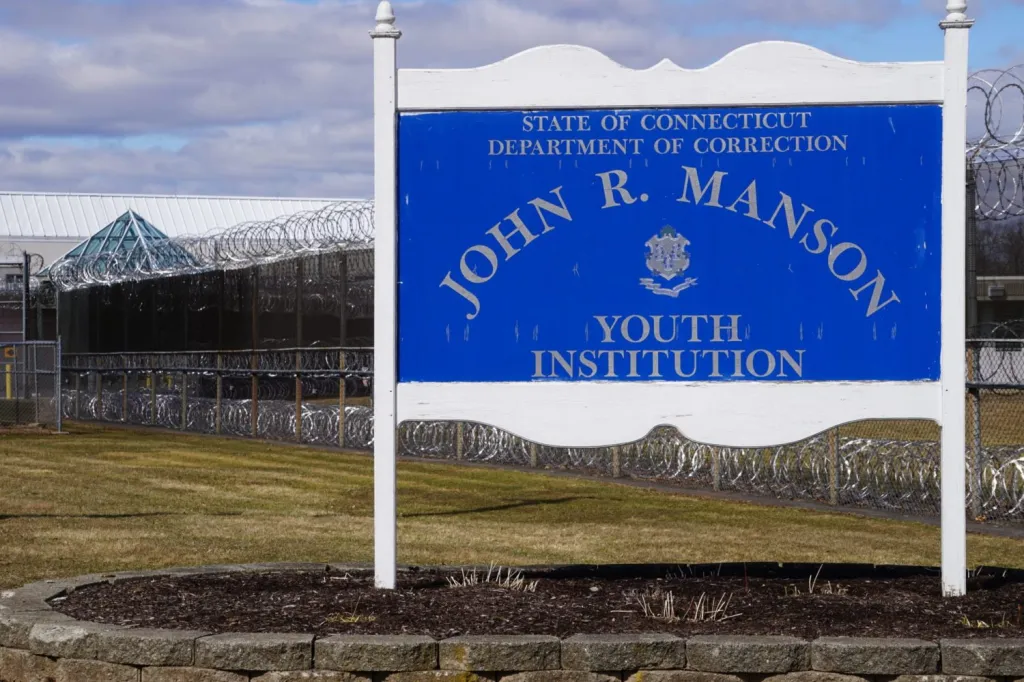

Connecticut’s juvenile prison has made progress in complying with a 2024 settlement with the U.S. Department of Justice, but concerns remain about the residential environment, as well as the education and mental health services incarcerated young people receive in Connecticut, according to a new report.

The “monitoring report,” released July 15, evaluated the state’s progress toward orders set out in the settlement agreement, which followed a two-year investigation revealing systemic problems with the way mental health and special education services were provided at Manson Youth Institution in Cheshire.

State and federal officials set goals for the facility, including required special education screening for incoming youth, new policies for reviewing and revising special education plans, and maintaining documentation of the services each individual receives. The settlement also required the state Department of Correction to limit the use of isolation as punishment.

Manson has made progress in some areas but fell short in some key places, evaluators found.

“The monitoring team recommends continued focus on priority areas to achieve substantial compliance and improve the quality of care and services for incarcerated youth at MYI,” the report said. “By addressing these challenges and implementing the recommended improvements, MYI can create a safer, more supportive, and rehabilitative environment for the youth in its care.”

Last week, correctional staff told members of the state’s Juvenile Justice Policy and Oversight Committee that they were making changes to improve their compliance with the orders in the settlement.

“When the juveniles came into our care, they came into a setting [that was] designed to house adult males,” Michael Pierce, warden at Manson Youth Institute, told the committee. “So when the investigation started, their focus was on education, mental health and our isolation procedures. And, rightfully so, we were found to be in non-compliance … we needed some help there.”

The report, which was conducted by monitor Michael Dempsey and a group of experts between November 2024 and April 2025, found that the facility had made some strides in decreasing the use of force and that staff were “professional and well-trained.” The facility has had 16 incidents where pepper spray was used between January and August of 2025. Most were related to fights or assaults, according to data provided by the agency.

But assessors highlighted several areas where the department continues to fall short: school days were cut short; young people had too much idle time without meaningful activities; residential rooms were poorly maintained; and mental health assessments and treatment plans lacked detail.

Connecticut’s acting Child Advocate Christina Ghio told the Connecticut Mirror that while it’s clear the department is starting to implement the changes outlined in the settlement agreement, there’s still “much, much more work to be done.”

State Rep. Toni Walker, D-New Haven, co-chair of the Juvenile Justice Policy Oversight Committee, acknowledged that the department had only just begun to implement some of the changes, and underscored the importance of getting regular updates about the department’s progress.

“We must not continue blaming the kids for failing. We have to take responsibility for the failure of not providing them with what they need,” Walker said.

Not a therapeutic environment

The report described the rooms of the facility as having “variable levels of cleanliness” and noted a significant amount of graffiti. The monitor recommended creating a “more homelike environment” using soft furniture, more sunlight and calming colors.

Pierce, the warden at Manson, told members of the JJPOC on Thursday that the facility was built in the 1970s to house adults. He said the department’s budget this year included $5 million for the remodeling of one of the cottages, and that they planned to buy softer furniture, like a new desk with a stool, nightstands and new mattresses, to make it appear more like a college dormitory.

The report also found that young people were spending what the investigators believed was too much idle time without meaningful activities. Their review found that young people were spending 3.5 hours after school in their rooms, where they also ate their meals.

“Youth spend most of their time in small, uncomfortable, drab, living units or rooms, leading to boredom and higher rates of incidents of violence,” the investigators wrote. “The team emphasizes the importance of developing more meaningful activities and programs, particularly on weekends when fewer programs are available to keep youth engaged, reduce idleness, and reduce the need for the excessive amount of operational room confinement hours.”

Pierce said the young people were out of their cells more than the legally-required five hours per day. He said that while they did have programs aimed at incentivizing good behavior in young people, the investigators “felt it was not as meaningful as it could be.”

Ashley McCarthy, spokesperson for the Department of Correction, said the department took the concerns seriously and was already working to improve conditions.

“Since November 2024 we have expanded programming to support positive engagement and skill-building,” McCarthy wrote in a statement. She cited fitness programs, chess tournaments and other sports, as well as weekend activities.

Ghio, the state’s child advocate, said, “ If we want to help the children who are there to rehabilitate, if we want to cut down on incidents, we need to have children engaged in meaningful activities throughout their day and on weekends.”

Sarah Eagan, executive director of the Center for Children’s Advocacy and former Child Advocate, said redesigning Manson into a place for adolescents could be “a little bit trying to fit a round peg into a square hole.”

“The state policy makers have a decision to make,” Eagan said. “Is this the setting, is this environment where we can best meet the needs of youth so that they may make gains and return safely and productively to their communities, or not?”

The report also detailed evidence of young people being disciplined using prolonged periods of isolation.

Lynnia Johnson, deputy warden for operations, told the JJPOC that the department has created a new policy around solitary confinement that requires staff members to check on young people placed in isolation every 15 minutes. While the isolation can last up to 72 hours, Johnson said no one had been placed in isolation for more than 1 hour since the policy began in March. She said that isolation was used only as a last resort.

Eagan said she believes the state should create a dashboard or framework for measuring how well the department was doing at keeping teens safe, the quality of services they were getting and the planning process for young people preparing to return to their communities.

Not making the grade

The report also pointed to problems with consistency in the young people’s educational experience, noting that between January and March 7, 2025, there hadn’t been three consecutive days in which all the students had a full day of school. (A November 2024 report from the Office of the Child Advocate found that in the 2022-23 school year, students lost nearly 25% of the hours they were supposed to be in school.)

The investigators said that dormitories would arrive 15 to 20 minutes late to school on a regular basis, meaning that students with special education needs wouldn’t always get their full services.

DOC spokesperson McCarthy said that students are taught by certified teachers in classroom setting, and that special education students receive their education from specialized teachers. She said “safety and security concerns” have sometimes impacted their schedule, but “we have taken steps to adjust routines to minimize these interruptions and ensure students receive a full school day.”

While the report praised the special education department for having certified staff providers on site and for its compliance process, the monitor noted that the teams of people responsible for students’ specialized education plans regularly reduce the amount of time and the services that the young people are supposed to receive — a serious problem that came to light in the original investigation.

About 61% of students in Manson Youth Institute are identified as having special education needs.

Addressing the JJPOC meeting, Manson Principal Matt Reinke said the facility was implementing a program called MAP, or Making Action Plans, where special education students identify a team of people and outside resources, like community programs, who can support them. They then create a roadmap for what success would look like after they leave Manson Youth Institute, and what steps they would need to take — like vocational training or college — that would help them reach their goals. Another module, Project Genesis, is also supposed to help young people explore possible careers and get ready to transition back into society.

Many of the young people at Manson are also behind in reading and math skills. The Office of the Child Advocate has reported that 70% of the teenagers assessed in June 2023 were reading at an elementary school level, and more than half were doing math at an elementary school level.

Reinke outlined the steps the facility has been taking to address those issues, including increased early data collection about students’ goals and their academic abilities. He said students whose skills are below their grade level receive one-on-one remediation, which he said was successful.

“ The vast majority of the youth that are at Manson are well below grade level in math and reading, right? And so it’s just unacceptable for them to have anything less than a full day of education,” Ghio said.

A plan for mental health treatment

Mental health was also a focus of the original investigation, in which the Department of Justice found that the facility did not properly assess the incarcerated young people for mental health needs or identify signs of trauma. The monitor’s report found that the treatment plans they reviewed for the teens “mostly lacked detail and at times failed to target the assessed needs.”

Dr. Michael Moravecek, the mental health supervisor at Manson Youth Institute, told JJPOC members that the facility has increased its staffing and developed a mental health assessment that is relevant for young people — including questions about education, friends and what they do in their free time. He said they’d introduced more detailed documentation, as the settlement agreement required.

Moravecek said it was “hard to measure” if the treatment was effective, and said his assessment of progress would be more “qualitative.”

Rep. Walker said she believes the department must develop ways of measuring the outcomes of any programs or changes that the Department of Correction undertook.

“I need to see the data, and I need to know — have you made improvements with the services you have been charged to provide with the state?” she said. “We’ve got to be much more transparent.”