There are two ways to think about “Nineteen Eighty-Four,” the great dystopian novel of totalitarianism that George Orwell wrote on the Scottish isle of Jura and published in 1949, six months before his death (at 46, of complications from tuberculosis). The first and most obvious way to think about it is as a midnight-dark tale of political oppression: the deprivation and bullying violence that dominate life in a ruthless authoritarian state. To a large degree, Orwell based the book on his perception of the Soviet Union, but he drew from other regimes as well, crafting a myth of what it’s like to exist as a humble pawn in a fascist prison state.

Yet that’s not ultimately the reason “Nineteen Eighty-Four” remains such a brilliant and mind-blowing book. Orwell was arguably the greatest psychologist of totalitarianism who ever lived. The words and phrases we get from “Nineteen Eighty-Four” that became famous (Big Brother, thoughtcrime, doublethink) remain more relevant than ever, and just as heady to ponder as they were 76 years ago, because what those words speak to isn’t merely the cruelty of life under totalitarianism — it’s the insanity of it, the way that fascist regimes destroy not just freedom but reality. That’s actually the cruelest thing about them.

“Orwell: 2+2 = 5” is Raoul Peck’s documentary meditation on Orwell’s writing, and on how his visionary insight applies to the world today. The film’s title piqued my interest, since that famous bit of business from “Nineteen Eighty-Four” — it refers to a torturer insisting to Winston Smith that he admit, in his mind, that 2+2 really does equal 5 — speaks to the essence of Orwell’s great theme, which is the metaphysics of fascism. If you’re willing to believe that 2+2 = 5, then you’ve allowed the state to determine reality to the point that it determines what’s going on inside you. At that point, you truly are owned; or maybe you don’t quite exist. But how does that dynamic work? How does it evolve? And how does it apply to the present day?

These are essential questions, but the surprise and, I have to say it, the disappointment of “Orwell: 2+2 = 5” is that the film doesn’t quite answer them. Peck, nine years ago, made the great ruminative documentary “I Am Not Your Negro,” based on the writings of James Baldwin, and that film was suffused with mystery. It was about racism and oppression, but Baldwin was a writer who dissected racism from a perch of perception that wasn’t just moralistic; he opened your mind to the deepest layers of identity. Whereas “2+2 = 5” is a movie that very much leans toward chronicling the brutality and violence of despotic regimes, and is less interested in exploring how they toy with your brain.

Peck fills the film with footage of contemporary autocracies and their infamous leaders (Marcos, Pinochet, Putin, Orbán). He also features images of the destruction of war, like the aftermath of the “strategic bombing” of Berlin during World War II — though that feels like a strange one to include, since it raises ethical questions about war crimes along the lines of what was explored in “The Fog of War,” but that all seems very separate from Orwell (plus, the world was fighting fascism during WWII).

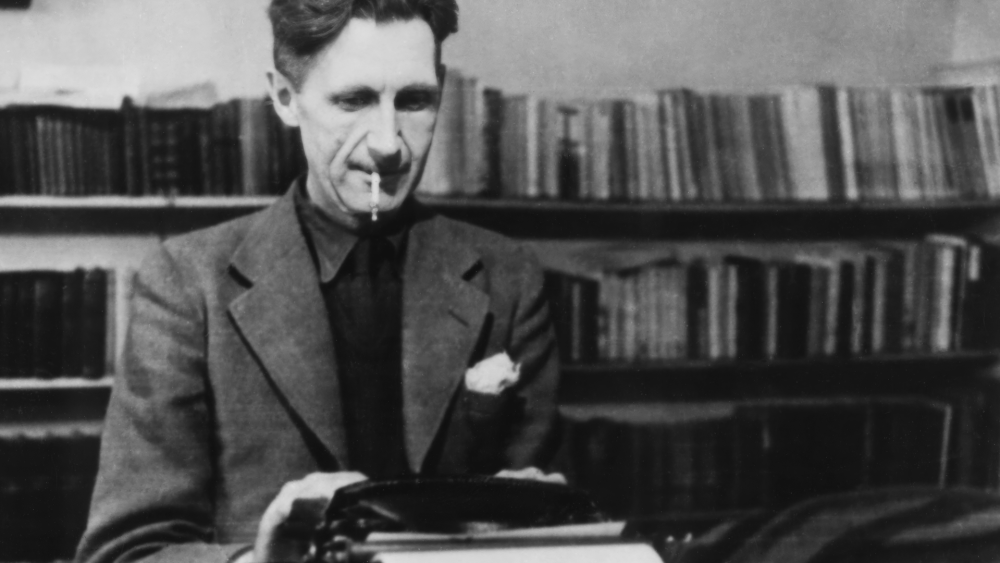

“Orwell: 2+2 = 5” is in part a portrait of Orwell, and on that score it’s quite compelling. We hear of his experiences as a teenager (when he looked round-faced and a bit smirky in a way that set him apart from his peers), or working for the imperial British state in Burma, which first imbued him with a sense of cosmic injustice. He saw the insidiousness of empire in his own middle-class desire to be a “gentleman,” and that pitiless ability to examine life through the prism of his own flaws is part of what made Orwell such a thrillingly honest writer. The film then traces him, through his diary and letters and other writings, over the last two years of his life, when he was stricken with tuberculosis and he moved from one health facility to the next, all the while finishing the manuscript that would become “Nineteen Eighty-Four.”

Orwell’s essays and novels are read on the soundtrack with puckish gravity by Damian Lewis, and as long as we’re hearing the flow of thoughts like “Everything in our age conspires to turn the writer, and every other kind of artist as well, into a minor official, working on themes handed down from above, and never telling what seems to him the whole of the truth,” or “Everyone believes in the atrocities of the enemy and disbelieves in those of his own side, without ever bothering to examine the evidence,” we can luxuriate in his 20-20 wisdom.

But when it comes to the works that made him famous, notably “Nineteen Eighty-Four” and “Animal Farm,” Peck makes the obvious but misguided decision to string together clips of the numerous film versions of them. The reason I think that’s a mistake is that with the possible exception of the 1956 version of “1984,” none of those films is really any good, and they slow the documentary down. (The version made in 1984, with John Hurt looking a lot like Orwell, is particularly drab.) These movies, too, miss the head-trip aspect of totalitarianism, and that’s partly because it’s such a difficult thing to dramatize. It would have helped to have had some critical voices explain Orwell’s insights into how the ultimate purpose of authoritarianism is to rob people of themselves.

The film is on more solid ground when it leaps to the present day and deals with the “surveillance capitalists” (there’s a clip of Edward Snowden speaking quite eloquently on the subject), or charts the banning of books, or the rise of orthodox media narratives, or phrases (“peacekeeping operations”) that mean anything but what they say. At this point, we start to touch the meat of the matter: how societies increasingly use technology to manipulate reality.

“2+2 = 5” is didactic in a way that Orwell, I suspect, would have looked a bit askance at. Except for a few shots of Chinese President Xi presiding over a military parade, the film’s image of totalitarianism leans far more toward right-wing regimes; to leave out Mao, or Castro, feels like a mistake. Yet the film’s timeliness is still a tonic, given that the spirit of autocracy looks more and more like a virus that now wants to take over the world. The film’s vision of the Trump presidency is scathing, and it puts its finger on one moment — the rationalizations made by George W. Bush to attack Iraq — as a key transitional event into the New Age of American Political Fakery. It was Orwell who got there first, showing how thoughtcrime arrives not just when leaders lie but when we stop believing we have the right to believe our own eyes.