Copyright Everett Herald

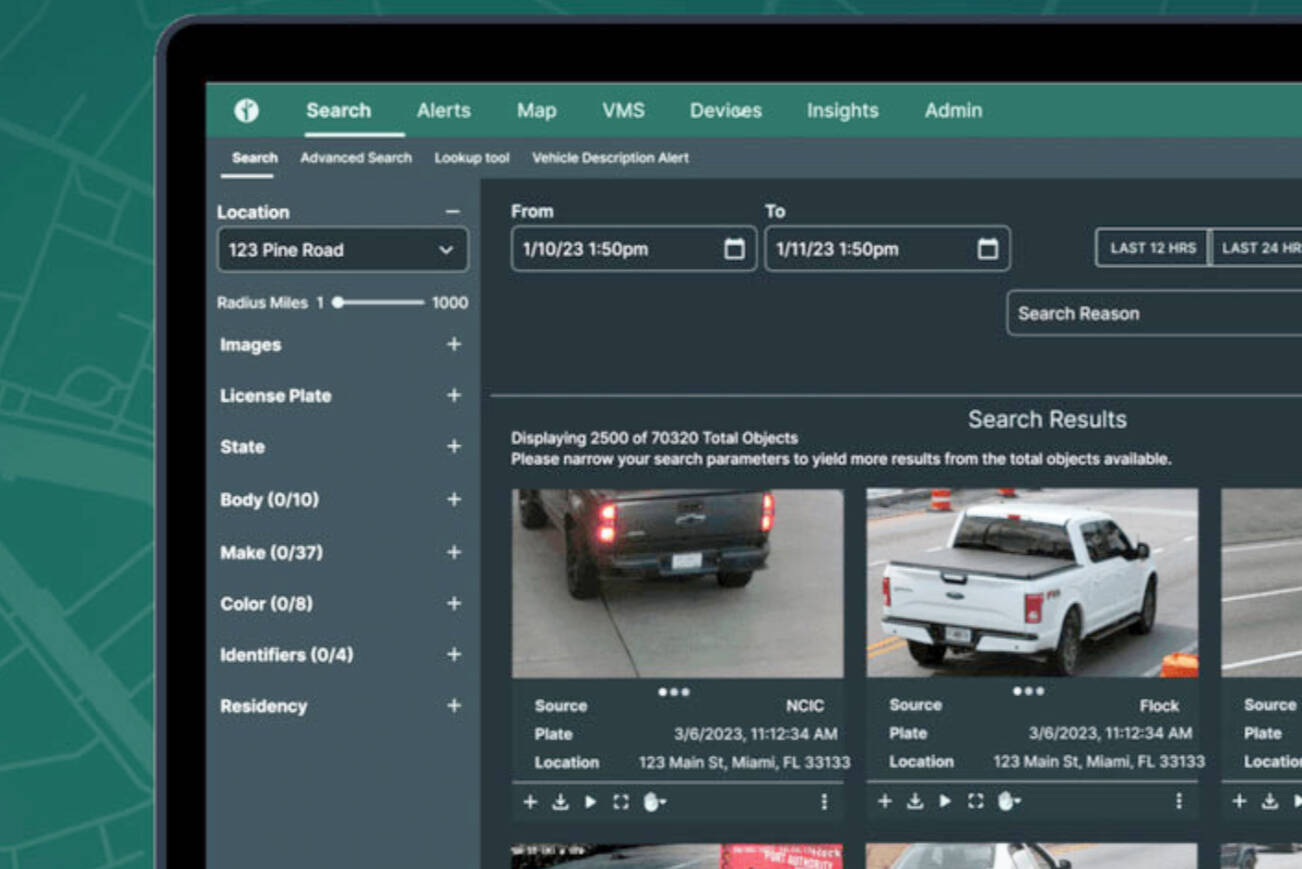

By The Herald Editorial Board A report by the University of Washington found that federal immigration agencies have used data from a system of surveillance cameras — called Flock Safety — that uses artificial intelligence to identify registered vehicle owners from license plate numbers and intended as a law enforcement tool and in use by local police agencies in the state and in Snohomish County. In some cases, it appears that federal use of local data has been without the full understanding of the agencies, local officials and the general public as to the breadth of that access, knowledge that should now prompt a full review of the systems by local and state officials, how they those systems are used and what limitations should be placed on the use and sharing of the data collected. In some cases, such sharing of data and analysis could be a violation of a state law, passed in 2019, that prohibits local law enforcement agencies from providing information not publicly available to federal authorities for immigration enforcement purposes. The report’s findings and further investigation by The Herald’s Jenna Peterson were detailed in The Weekend Herald, as was the response of at least one state lawmaker, state Sen. Marko Liias, D-Edmonds, that federal immigration access to the local data violated the spirit if not the letter of the state law. ”Leaving the Door Wide Open,” which details the data shared by Flock cameras operated by local law enforcement agencies in Washington state with federal immigration agencies, is a report released Oct. 21 by the University of Washington Center for Human Rights, part of the Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies. The report is a followup to the center’s 2022 report, “Who’s Watching Washington,” which first raised concerns about automated license plate reader technology and its potential uses — beyond local law enforcement investigations — for immigration enforcement and the criminalization of access to productive health care. Following the report, The Herald reviewed records from Arlington, Everett, Lake Stevens, Lynnwood, Marysville, Mill Creek and Mukilteo, all clients of the Flock system. The report noted that federal agencies, including Immigration and Customs Enforcement and Customs and Border Patrol, had access to Flock networks across the state, notably from Arlington and Mukilteo, and that out-of-state agencies conducted searches related to immigration from data collected in Mukilteo and Lynnwood. The UW’s original report described how the technology can identify a vehicle’s registered owner with a full or partial license plate number, but also how a network of the cameras can be used to track a vehicle’s location through one community and to the next and spot specific vehicles placed on a “hot list.” Among the concerns noted in the most recent report, the center noted: Arlington’s police department was among eight city or county law enforcement agencies in Washington state that had enabled one-on-one sharing of its Flock data with Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) at some point during 2025. Between May and August, CBP gained apparent “back door” access to license plate data from at least 10 other agencies that the agencies’ local governments had not explicitly authorized or were not fully aware of. In limited cases, agencies in the state conducted searches of Flock plate data on behalf of either CBP or ICE, while law enforcement agencies outside of the state had conducted their own searches of Flock data from agencies in this state, which could be a violation of state law. The report’s investigation, it says, raises doubts about the transparency and accuracy of Flock’s description and explanation of its technology and clients’ ability to control and understand the data being gathered, how it is analyzed by AI systems and how it’s being used. The report should further highlight the ubiquity of such camera systems and the need for clearer understanding among the general public. Law enforcement agencies aren’t the only Flock customers; the camera and AI systems are in use by other local governments outside of police agencies, neighborhood associations and businesses, including The Home Depot, Lowe’s hardware and some mall operators. The report comes as debates have expanded as other cities and counties consider the technology, now said to include a network of some 80,000 cameras in 6,000 U.S. communities, with the prediction by the company’s CEO, Garret Langley, that Flock will eradicate nearly all crime in the U.S. within a decade. The cameras and their AI analysis, in use by more than 80 law enforcement agencies in Washington state, are credited with decreases in vehicle theft and location of suspects in other investigations. And the sharing of data among departments has been used in location of missing persons, such as those with Alzheimer’s disease or dementia. At the same time, however, the recent report has provided a better focus into how the data the cameras collect and that its AI systems analyze can be used in ways that are not necessarily fully understood by local government officials or their constituents. For example, Arlington, according to information from the UW report shared with The Herald, directly shared its network with CBP and the U.S. Postal Inspection Service, which focused its investigation on locating undocumented immigrants for a Department of Homeland Security task force. Arlington’s city administrator told The Herald it was working with Flock and on its internal controls to “ensure transparency and adherence” to state law. (Also of concern, out of The Herald’s reporting, was the refusal by the City of Arlington to release a “network audit” for its Flock system — logs of searches made into an agency’s data — as part of a public records request. Five other cities complied with the request, but Arlington denied the release saying the audit did not qualify as a public record. But the state’s public records law is clear that a public record is any writing — including photos, maps, videos, voicemails, webpages, emails, text messages and social media content — that is prepared, owned, used or retained by any state or local government agency that contains information that relates to the conduct or performance of government; the audit clearly fits that language and none of the law’s exemptions apply to the Flock search audits. Arlington should comply with the lawful request.) Many local governments, the report found, may not have understood that they had enabled sharing of their data with federal agencies, a feature called “nationwide lookup” that allows peer-to-peer sharing of data. But as ICE and other Homeland Security agencies do not have contractual relationships with Flock, local agencies may have assumed federal agencies would not have access to that data. Indeed, at least one local agency told The Herald it was not aware of the federal access until the release of the UW report. The Flock Safety system can be defended as a legitimate law enforcement tool; there should be little expectation of privacy assumed for a broadly visible number attached to a motor vehicle. But the recent revelations call for a broader review by local governments and state lawmakers, better understanding of that tool’s features and controls and consideration of the opportunities and risks that it and similar technology may pose in the future. That concern was well stated during a recent Lynnwood City Council meeting that followed the release of the UW report, The Herald’s Peterson reported: “The real question is not just, ‘Does this solve crime?’” Lynnwood resident Xavier Rodriguez said at the meeting. “It’s, ‘What kind of infrastructure are we building for the future, and who ultimately controls that data?’ The long-term civil liberties risked are far greater than the advertised short-term benefits.”