By Ross Douthat / The New York Times

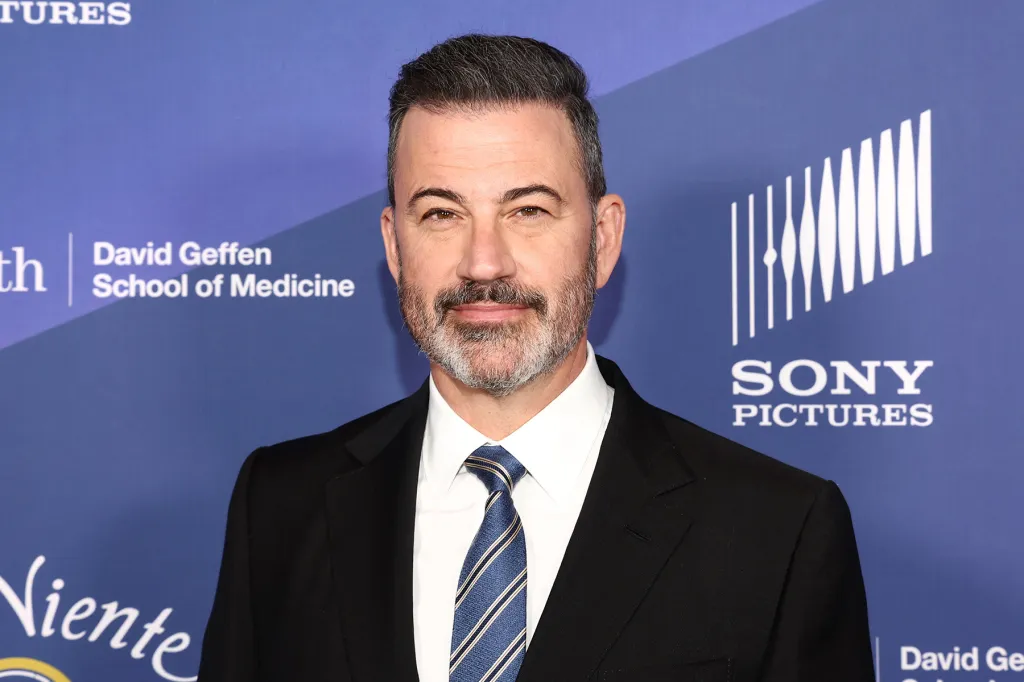

Seeing Jimmy Kimmel suspended from his late night show with, shall we say, the strong encouragement of the chair of the Federal Communications Commission, some conservatives immediately made an analogy to the “jawboning” that the Biden White House used to encourage social media companies to practice various forms of covid-19 censorship.

This, in turn, prompted an interesting question from liberal writer Derek Thompson. Even conceding that the Bidenistas might have acted inappropriately, he wrote, their push to police pandemic speech reflected a desire to serve the public interest by preventing unnecessary deaths. Whereas the Kimmel suspension, he argued, looks like pure partisanship: “I haven’t heard anybody even pretend that there’s a deeper principle at stake here.”

I think many conservatives do see a civic-minded purpose here, and I’ll accept Thompson’s challenge and try to articulate it. The argument starts with the assumption that America’s leading cultural institutions — broadcast networks, movie studios, major universities — are private enterprises but also a kind of public trust, with civic as well as commercial obligations. (On this point, at least, many liberals would agree.)

It’s possible to be a good, civic-minded steward without being perfectly politically neutral. Most cultural institutions have been staffed primarily by liberals since time immemorial (or at least since the 1960s), and while this has always been a source of conservative complaint, it’s something the right learned to live and work with; and even profit from, through the talk radio and Fox News alternatives.

From the conservative perspective, though, the nature of the stewardship changed in the 2010s. There was a shift within liberal culture, an increasing politicization, a ratchet to the left. This shift was mediated by generational conflict and novel technological forces and then embraced by a range of institutions, from academia to Hollywood to Silicon Valley, who collectively decided to enforce an emergent left-wing orthodoxy; through high-profile firings, novel speech codes and statements of ideological loyalty as a requirement for academic employment.

Late night television was an interesting bellwether. This was something I wrote about in the run-up to the 2016 election, describing the strangeness of watching a cultural zone that used to be pretty apolitical suddenly populated by a raft of increasingly partisan comics, Kimmel among them, each offering a different variation on a hectoring progressivism.

It wasn’t the marketplace of ideas or the imperatives of commerce that drove this shift: It was the internal dynamics of elite culture, and a failure of stewardship on the part of the people at the top. And that failure led first to an extended period of soft censorship in American life, and then to the political revolt against cultural progressivism. President Donald Trump’s 2016 upset was the foretaste; his 2024 return to power was its culmination.

In the aftermath, my sense is that many stewards of cultural institutions are aware that they have a problem, that they’ve lost the public trust or market share or both. The leaders of the Ivy League would like to have more ideological diversity and national credibility. The leaders of the big networks would like to cut themselves loose from their failing late night TV model. The leaders of Disney would like to figure out how to make unifying entertainment again.

But they are still dealing with internal ideological pressures; so to be able to reform, they need pressure from the outside to do the right thing.

This, then, is the arguable civic purpose of the Trump administration’s culture war. Sometimes it takes a systematic form, like the efforts to induce universities to change the way they admit and hire and handle speech issues. Sometimes it seizes on targets of opportunity, like a late night host bizarrely and offensively attacking “the MAGA gang” for correctly recognizing that the man who assassinated a conservative icon was probably left-wing. But in each case the purpose is to give cultural institutions a reason or an excuse to row back toward the great American middle.

I think this perspective has merit, but it also has a crucial problem: The president of the United States does not share it. Or rather, he would happily go beyond it, toward a world where most cultural institutions are simply subservient to his personal interests, his reputation, his amour-propre. Where journalists are guilty of “hate speech” if they’re mean to him. Where this newspaper has to pay him big, big reparations for underrating his celebrity and genius. Where the culture war is a way to empower and enrich his friends.

Certain conservative arguments right now dance around this reality; around the things Trump himself says, the most outlandish lawsuits that he files, the crudest threats he issues.

Conservatives will criticize White House subordinates, like Pam Bondi, for being too hostile to free speech. But Trump is the leader, the instigator, the king; not yet superannuated, indeed more powerful than ever.

So however the right justifies its cultural counteroffensive to itself, to the wider country it may feel like a rerun of peak wokeness; except instead of fealty to a strange new ideology, the unwelcome demand is fealty to Trump himself.