Copyright cleveland.com

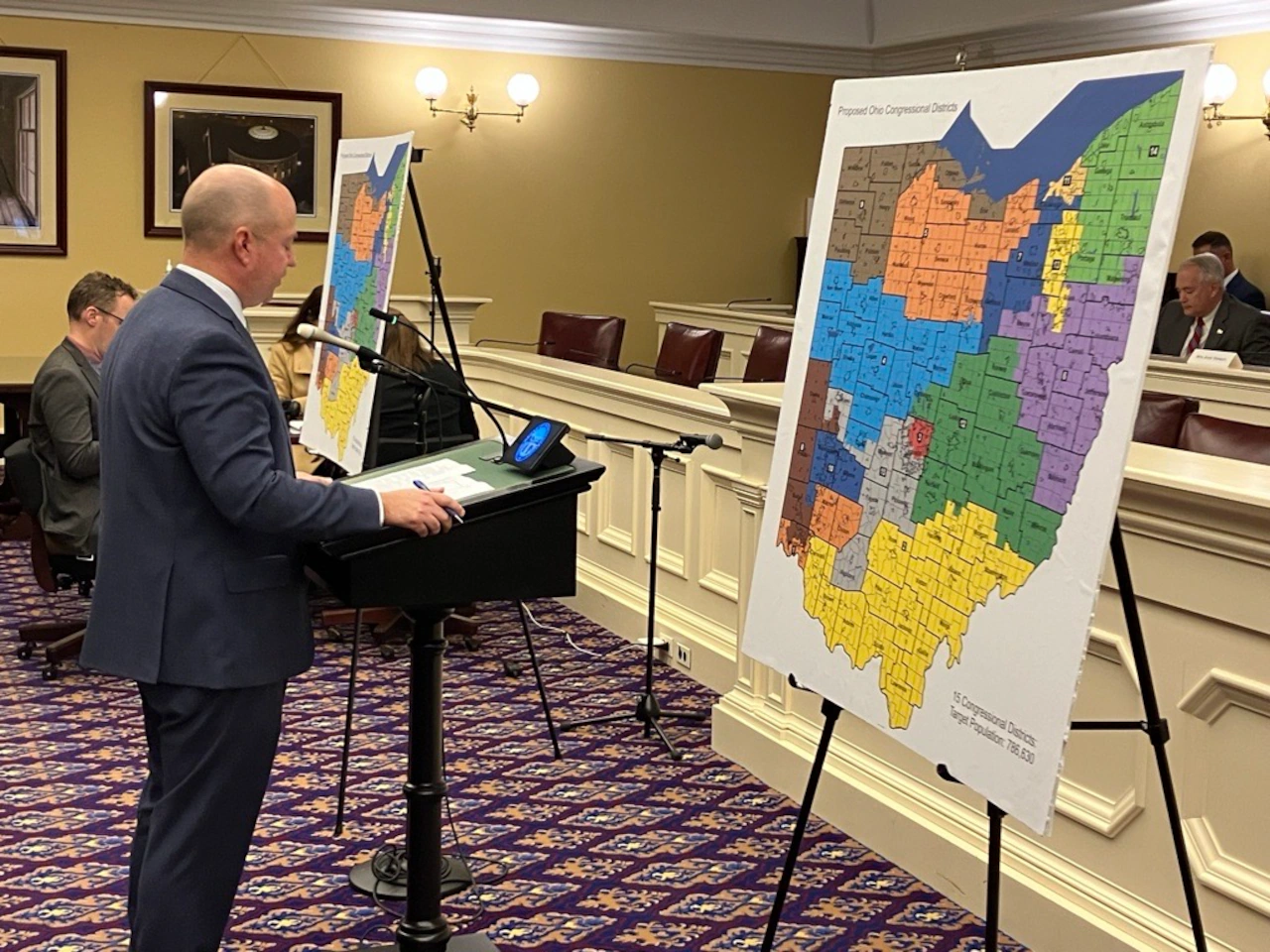

COLUMBUS, Ohio—Ohio’s redistricting process, passed by large bipartisan majorities last decade, has faced loud and unceasing criticism that it allows the state’s Republican majority to push through gerrymandered districts that give GOP candidates an unfair advantage. But last week, Republicans and Democrats on the Ohio Redistricting Commission unanimously passed a new congressional redistricting plan for the next six years. The vote came two years after the seven-member commission unanimously approved new state legislative maps for the rest of the decade. Does this mean that, after all the public ridicule, court battles, and even a failed statewide referendum to replace it, Ohio’s redistricting process is actually working the way voters were promised? And will it keep working this way in the future, or will redistricting reform activists try again to convince voters to completely overhaul the process? “I don’t think it’s necessarily working as intended, but it is imposing some constraints on Republicans from imposing a maximal gerrymander,” said Kyle Kondik, an Ohio native and managing editor of Sabato’s Crystal Ball at the University of Virginia’s Center for Politics. “If you’re a Democrat,” Kondik said, “it’s better than nothing.” Initial hiccups Ohio’s last two redistricting processes have certainly gone more smoothly than the first time the state’s redistricting rules were used in 2021, when Republicans unilaterally pushed through new U.S. House and state legislative district lines despite repeated rulings from the Ohio Supreme Court that the maps were unconstitutionally gerrymandered. In both 2023 and this year, Republicans seemed poised to ram through redistricting plans designed to help their candidates win as many seats as possible. But, in each case, GOP leaders ended up trading some concessions to the Democrats in exchange for the imprimatur of bipartisan support. Ohio’s new congressional map makes it more likely for Republicans – who already hold 10 of the state’s 15 U.S. House seats – to flip two more Democratic-held U.S. House seats starting next year. Critics on both sides The new map drew scorn from both sides of the political spectrum. Some conservatives fumed that Republican leaders should have muscled through a plan with 13 GOP-friendly districts, while many liberals denounced Democratic redistricting commissioners for supporting a plan more advantageous to Republicans than the 2021 congressional map the Ohio Supreme Court declared to be a GOP gerrymander. House Speaker Matt Huffman, a Lima Republican who helped write Ohio’s current redistricting rules, said he and legislative leaders from both parties struck a deal because of “uncertainty” on each side. Republicans, Huffman said, were afraid that if GOP lawmakers pushed through a 13-2 redistricting plan, Democrats would organize a statewide referendum to repeal it. Democrats, meanwhile, were worried the referendum effort would fail and they would be stuck with a worse map. Conservatives, Huffman said, should see that the new map is “the most Republican map that there has been in the history of the state of Ohio.” He said most Republican criticism died down when GOP leaders like himself explained both what the Ohio Constitution’s restrictions are and pointed out that the new map positions Republicans to unseat Democratic U.S. Reps. Marcy Kaptur of Toledo and Greg Landsman of Cincinnati. Huffman also ridiculed critics on the left, who packed Ohio Redistricting Commission meetings last month to loudly heckle the new map and the overall redistricting process that produced it. “I know a lot of people like to say, ‘Well, that’s not what we really voted for.’ Well, if you voted so that both parties have a seat at the table, both parties actually gain something that they might not have if an alternative happened, I’m not sure what other system is ever going to be better,” Huffman said. “I think for a lot of people,” he added, “the system that’s better is, ‘Give me everything that I want.’” One critic is Common Cause Ohio Executive Director Catherine Turcer, who supported the 2018 state constitutional amendment setting up Ohio’s congressional redistricting rules but is now a leading redistricting reform advocate. The state’s current redistricting process “can have good results,” as it does put pressure on elected officials from both parties to reach some sort of agreement, Turcer said in an interview. But the incentive to strike a deal this year, she noted, wasn’t anything prompted by the state constitution’s redistricting rules, she noted. Rather, it was each side’s fear that they would lose a statewide referendum over repealing a lopsidedly GOP-friendly redistricting plan. Public input shut out Turcer’s biggest criticism is that any deal struck between the two parties is worked out by their negotiators in private meetings behind closed doors without public input. The newly approved congressional map, for example, was first shown to the public by legislative leaders only a day before it was passed – and only then by a single picture of the proposed map, without any details. Both Huffman and Senate Minority Leader Nickie Antonio of Lakewood, the Ohio Redistricting Commission’s Democratic co-chair, have previously said that such closed-door negotiations are a feature, not a bug, of the state’s redistricting process, as it allows for frank and productive discussions. Turcer scoffed at that notion. “I mean, this works really well for them,” she said. “But for the public, this is a violation of trust.” National tug of war While Ohio had to redraw its congressional districts this year (the 2021 redistricting plan expired after only four years because it lacked bipartisan support), the state’s latest round of redistricting comes amid an arms race in other states to more aggressively and overtly gerrymander U.S. House districts. Several red states, including Texas, North Carolina, and Missouri, have moved to create new districts designed for Republicans to build on their narrow House majority in 2026. In response, California voters approved a redistricting measure last week that opens the door to Democrats picking up five additional House seats. Other blue states, including Virginia, are also eyeing a similar move. However, all this escalation has, so far, resulted in little net change for either side, Kondik argues. Whether Ohio’s changes to its congressional district lines could affect control of the U.S. House next year will depend on several factors, Kondik said. Among them is whether 2026 is a “wave year” for either party, as well as the result of a much-anticipated U.S. Supreme Court ruling on the federal Voting Rights Act that could result in several blue-leaning, Black-majority districts being redrawn. “There are all sorts of ifs and buts and about redistricting,” Kondik said. “But if the Democrats win a 218-217 majority next year, and they lose one seat in Ohio instead of two or three, you know, that could be the difference.” What’s ahead While Ohio’s congressional and legislative maps are now set until after the 2030 U.S. Census, it seems likely now that the next round of redistricting will shape up much like the last two rounds have, said David Niven, a University of Cincinnati political science professor and former speechwriter for Democratic Gov. Ted Strickland. “I certainly think that’s a plausible scenario that we continue with this stalemate followed by an ‘abracadabra’ map,” Niven said. However, he continued, the current nationwide push for states to gerrymander their maps, as well as the criticism Ohio Republicans have received from their fellow conservatives, suggests the state’s next redistricting process will draw a lot more pressure from national political leaders. “I think we can expect a national imposition on this process that’s even greater going forward,” he said. In addition, redistricting reform advocates haven’t given up the fight to pass a new constitutional amendment, despite last year’s failure of Issue 1, Turcer said. It’s not yet clear when activists might launch a renewed campaign, as it will take time to figure out what changes need to be made to ensure it succeeds. That includes getting public input on how to improve and streamline the 23-page-long proposed redistricting process shot down by voters in 2024, Turcer said. It also includes preparing a preemptive information and advertising campaign in favor of any new proposal, in case Republican officials again approve ballot summary language that doesn’t paint the proposal in a favorable light, as they did last year. “We’ll be back,” Turcer said. “We also know that we need to be thoughtful. We need to plan well, and everything takes longer than we want it to.”