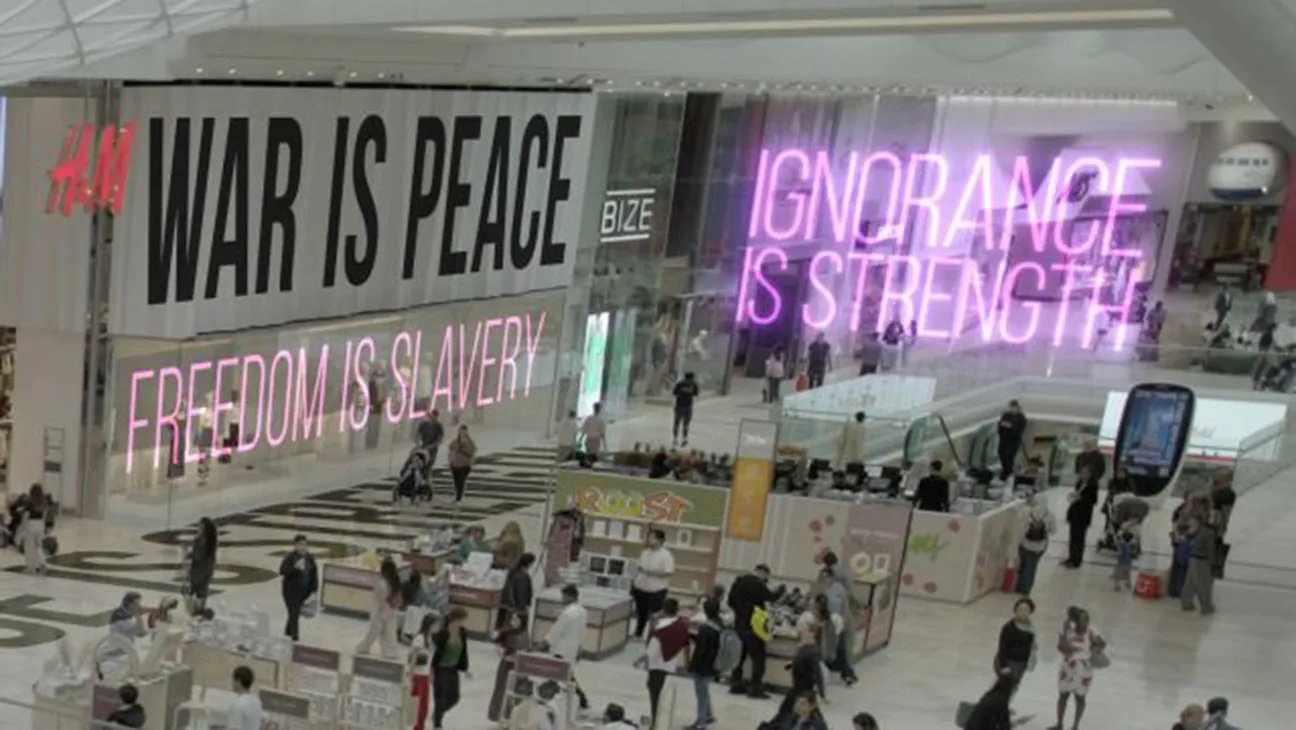

At a time when so many major Hollywood distributors are avoiding political stories for fear of offending or provoking, the new documentary Orwell: 2+2=5 is refreshingly direct. The director, Raoul Peck, intersperses readings of 1984 and Animal Farm author George Orwell’s writing about authoritarianism with footage of President Donald Trump and his supporters. Where the film stands on the trajectory of U.S. democracy is clear.

But Orwell: 2+2=5, of course, isn’t just an argument about Trump’s America. With the help of material from the Orwell estate, the Neon film attempts to shed new light on its namesake author (née Eric Arthur Blair), whose chilling view of totalitarianism has long petrified high school students making their way through summer reading lists and stemmed from Orwell’s own experience.

The movie charts Orwell’s life story with a special focus on his political awakening, starting with the author’s birth in India under British rule and lingering on his disillusionment with the empire as he briefly served as a police officer in Burma. Ultimately, Orwell ends up fighting in the Spanish Civil War with a Republican militia before turning to literature to make his political stand, finishing his masterwork 1984 just months before his death in 1950.

As he tells Orwell’s very 20th-century story and quotes his writing (performed by Homeland actor Damian Lewis), Peck intersperses images from authoritarian actions past and present to paint a picture of humans falling again and again into repressive government structures. Vladimir Putin justifying his attack on Ukraine by saying he was going to “de-Nazify” the country makes an appearance, as does footage of the persecution of Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar.

In an interview with The Hollywood Reporter on the eve of the film’s release (Oct. 3 in New York and Oct. 10 in L.A.), Peck explains his essayistic approach to telling Orwell’s story. He also describes why he didn’t just want to make a film that spoke to the current moment. “If you watch the news [today], I could change every single clip of this film,” he says. “But my intent was not to make a film for the current moment. Even though it is current, I wanted to make a film that will still stay in 10 years, 20 years, 30 years.”

I could imagine a version of this film that would let viewers draw their own conclusions about similarities to the present. But this one actually includes contemporary footage. Why did you take that approach?

It was so obvious. If you read a passage of the third chapter of 1984 where Winston is describing what is happening on the Mediterranean, of course those images will come up immediately. There was no hesitation. What I do, though, is make sure that I don’t overkill. I make sure that I leave space for the audience to make up their own minds. What you might feel as a sort of quantity of images, the density of all this is in fact because we are in a very dense moment where we are bombarded every day with hundreds and thousands of images. And there is a time where you can’t really play with nuance.

And last on that question, I think what people feel massively is the fact that so many places of conflict, of killings, of authoritarian regimes [are] put together in one narrative. I experience it with younger people: Suddenly they realize, “Oh my god, that’s way bigger than what happened in my own country or in one part of the planet.” It is an incredibly large movement to a point where you can say, well, the 85 percent of Oceania that Orwell is talking about, it’s the planet. It’s the amount of people that are in really dire situations. [In 1984, Orwell’s protagonist writes, “If there was hope, it must lie in the proles, because only there in those swarming disregarded masses, 85 percent of the population of Oceania, could the force to destroy the Party ever be generated.”]

There are themes that authoritarian regimes have in common, is what you’re saying?

That they have in common. I think that’s one of the most important reasons for Orwell to write 1984, where he said, I put the [setting] in the U.K. because I wanted to show that totalitarianism doesn’t only happen in totalitarian countries, it can happen here as well. He saw the incentive toward totalitarianism as a big problem. And indeed it happened everywhere. I had no problems finding clips far back, and actually today as well. If you watch the news [today], I could change every single clip of this film. But my intent was not to make a film for the current moment. Even though it is current, I wanted to make a film that will still stay in 10 years, 20 years, 30 years.

Did you anticipate, when you first set out to make this film, just how topical the story might be by the time it was released?

That happens to my films a lot. And the reason for that is I am making films as a way to implicate myself to what’s going on around my life, around where I live, around the world. I came to cinema through politics. I never came to cinema because I wanted to go Hollywood or just to be an artist, a filmmaker. In fact, before studying film, I studied industrial engineering. So it was a political decision and a political decision that fits Orwell’s decision as well. When he said, “Animal Farm was the first book I wrote where I tried to mix politics and art,” that is what I’ve always tried to do throughout my life as a filmmaker.

What do you think Orwell would make of the state of the world today, after having studied him so closely?

I’m pretty sure he would say, “I told you so.” Because he had an insight about how politics functions, how people function, because he had been there himself. He’s not a desk intellectual. The fact that he was born in India and then went as a soldier to Burma, [where he was] as he says an imperialist tool and bullying people, arresting people, all sorts of things that he was not very proud of. And then finally the Spanish Civil War, where he said, “After that war I knew where I stood.” Those are important moments in his life that shaped him. He knows from the inside what human beings are capable of.

The sentence that we have in the film where he says, “People are always willing to condemn the other without recognizing what they are doing themselves and without bothering to analyze the evidence,” we are exactly in that situation. Whether it’s in Israel, Palestine or in the United States right now, everybody is accusing the other, and it’s like a total collapse of everything we’ve known as fundamental landmarks. Words doesn’t mean the same thing. Again, we come back to “newspeak,” to Orwell. Somebody can say “democracy” or “free speech,” and it’s two different [meanings]. So how do you engage in a conversation?

So we are in a very, very bad place right now. Once you start to say, “Well, there are alternative facts,” where do you go with that? When science doesn’t mean anything? Look at the announcement about Tylenol. We are in such an absurd world and Orwell would have said, “What the…?” Because he would think that there should be some common sense, what he repeats again and again, where is all common sense? Now I’m afraid that we are in, not a point of no return, but the return will cost us a lot of time.

What is your take on the current environment for nonfiction films with strong political messages and what do you hope happens moving forward?

I think we are in a time where everybody’s looking for cover. People are afraid, people are terrorized. And that was the intent. That’s how a totalitarian regime operates. They choose one person, one group, one entity, and they attack it. And it’s a way to terrorize everybody else. And the wrong reaction of society is to let that person alone or that entity alone. And sometimes, thankfully, there is a reaction, like in the case of Jimmy Kimmel, there was some collective reaction, but if you know the history of the rise of antisemitism in Germany, within a few months you can be totally intimidated and you don’t resist. And it’s hard. I’m not saying it’s easy. People sometimes expect some heroic situation. I say, no, no, it’s you are in the subway, somebody is being attacked. Do you stand up or not? And if you stay seated, you will regret it at some point. And it’s those little renouncements that at one point paralyze a whole society. And when they understand it, it’s too late.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.