Copyright mirror

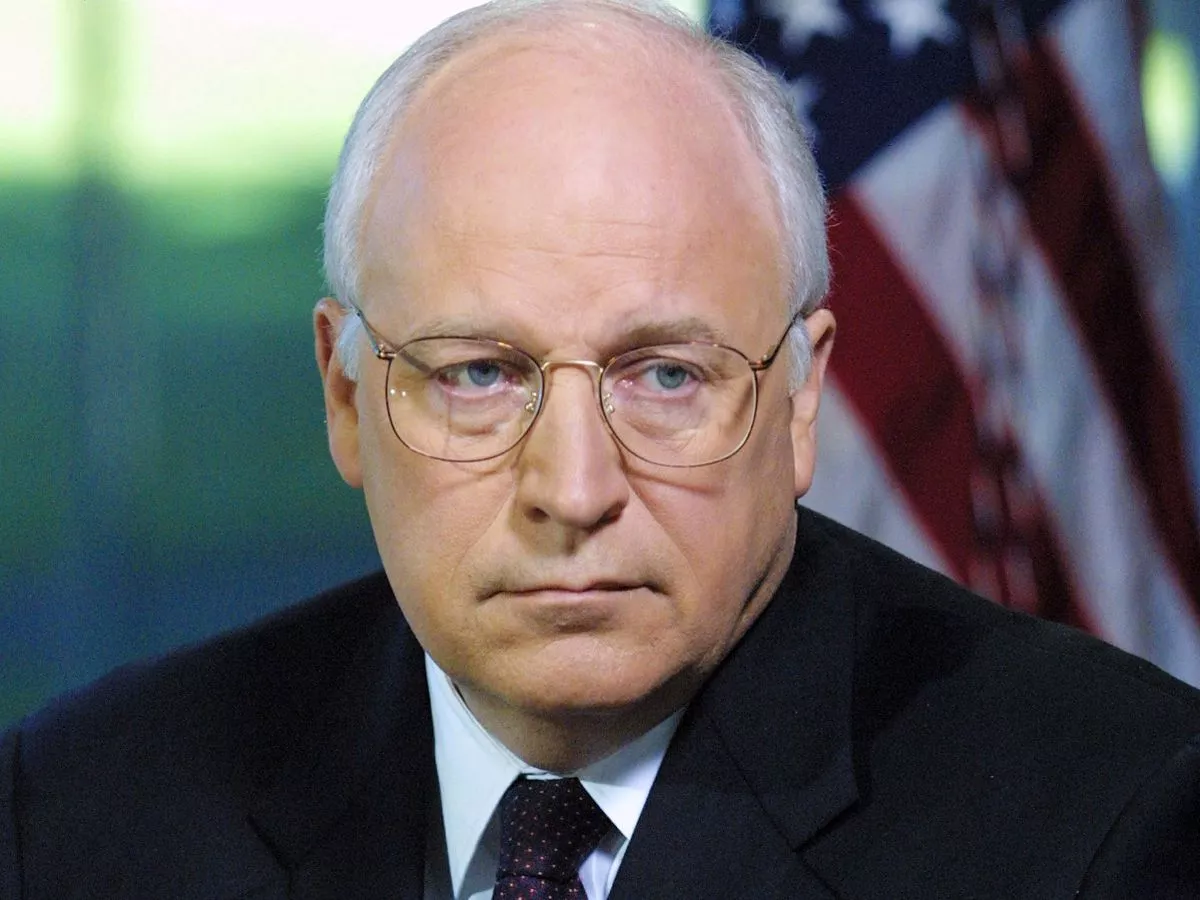

As US Vice President Dick Cheney was the most powerful - and perhaps most feared - deputy in American history. The “architect of the war on terror” and champion of torture in all but name, he was the driving force in convincing Britain to support the Iraq war. As the man who turned a presidency into a fortress of secrecy, the 84-year-old, who died on Monday, leaves behind a legacy soaked in controversy and consequence. For much of his career, Cheney was content to lurk in the shadows. He wasn’t a man for the campaign trail or the TV camera. His power came from the corridors, not the crowds. While George W. Bush was the public face of the White House, Cheney was the hand on the tiller - calm, ruthless and utterly convinced he was right. In his final years, however, Cheney, still a hardline conservative, nevertheless became largely ostracised from his party over his intense criticism of Donald Trump , whom he branded a “coward” and the greatest-ever threat to the republic. Announcing his death, his family said: “His beloved wife of 61 years, Lynne, his daughters, Liz and Mary, and other family members were with him as he passed. The former Vice President died due to complications of pneumonia and cardiac and vascular disease.” Born Richard Bruce Cheney in Lincoln, Nebraska, in 1941, he grew up in the windswept town of Casper, Wyoming. After a rocky start at Yale University, he returned home after being kicked out, earning degrees from the University of Wyoming and finding his way into Washington as a congressional aide. His rise was steady, not spectacular. But behind the scenes, he built a reputation for discipline, cunning, and a refusal to be outmanoeuvred. By the time he became Gerald Ford’s Chief of Staff in the mid-1970s, Cheney had already mastered the dark arts of bureaucratic power. When Ford lost the presidency, Cheney turned to Congress, serving six terms in the House of Representatives before becoming Secretary of Defence under George H. W. Bush. He oversaw the first Gulf War with military precision - decisive, swift, and bloodless, at least from an American perspective. It would become the high point of his reputation before the storm to come. After a stint in the private sector as CEO of Halliburton, the oil services giant, Cheney was pulled back into politics as George W. Bush’s running mate in 2000. Many saw him as the “grown-up” on the ticket - a safe pair of hands. Few realised that he would emerge as the most influential vice president in US history. Then came September 11, 2001 and with it, Cheney’s defining moment. As smoke rose over the Pentagon, he retreated to a secure bunker beneath the White House and assumed command while the president was still in the air. Those chaotic hours crystallised Cheney’s worldview: the world was dangerous, and America must never again appear weak. From that day forward, he pushed for a doctrine of pre-emptive war, enhanced interrogation, and surveillance on a scale the world had never seen. Cheney’s influence on Britain’s fate was profound. He found in Tony Blair a willing partner, and the two nations marched in lockstep into Iraq on the now-discredited claims of weapons of mass destruction. It was Cheney who pressed hardest for regime change in Baghdad, convinced that Saddam Hussein’s removal would reshape the Middle East. Instead, it unleashed years of bloodshed and chaos that scarred both nations. Behind the scenes, he cultivated what aides called the “Cheney Doctrine” - a belief that America should act unilaterally, without apology, and without restraint. He championed Guantánamo Bay, defended waterboarding, and authorised “extraordinary rendition” - polite Washington-speak for kidnapping suspects and sending them to secret prisons overseas. Critics accused him of turning the war on terror into a war on truth. His domestic controversies were no less notorious. In 2006, during a quail hunting trip in Texas, he accidentally shot his friend, lawyer Harry Whittington, in the face with a shotgun. The incident hurt Cheney's popularity standing in the polls. According to polls on February 27, 2006, two weeks after the accident, Cheney's approval rating had dropped five percentage points to 18 per cent. The incident became the subject of a number of jokes and satire. The image of the vice president spraying birdshot while Whittington later apologised to him became a darkly comic metaphor for Cheney’s style: deadly, unapologetic, and somehow always in control. Yet for all the scandal, there were flashes of humanity. Cheney, who suffered several heart attacks from his forties onwards, became one of the first major figures to receive a heart transplant while still alive. He once said: “I reached a point towards the end on the old heart where I had trouble getting out of a chair. All I wanted to do was get out of bed in the morning and walk to my office and sit back down in the chair. Now I throw 50-pound bags of horse feed in the back of my pickup truck, and I don't even think about it. I'm back doing those things.” The Vice President spoke openly of his daughter Mary’s marriage to another woman, even as his party’s base railed against same-sex unions. “I think that freedom means freedom for everyone,” he said. “As many of you know, one of my daughters is gay, and it is something we have lived with for a long time in our family. I think people ought to be free to enter into any kind of union they wish. Any kind of arrangement they wish.” His relationship with the UK remained both strategic and symbolic. British troops followed American orders in Iraq and Afghanistan , and Cheney’s influence echoed through Downing Street. Former officials recall him as both “immovable” and “intimidating”, with one describing meetings at Number 10 as “like being briefed by a general who’d already decided the battle plan.” When he left office in 2009, Cheney’s approval rating languished at a meagre 13 per cent. Yet he seemed almost to relish his unpopularity. “I didn’t take an oath to be popular,” he once snapped. “I took an oath to defend the Constitution.” Even out of power, he remained a hawkish voice on national security, always unrepentant, unbowed, and utterly convinced history would vindicate him. In his 2011 memoir, In My Time , he offered no apologies. “I did what I thought was right,” he wrote. “And I’d do it again.” It was a defiant farewell from a man who viewed politics not as performance, but as a series of necessary calculations. To his admirers, Cheney was a patriot who made the hard calls others shied from. To his detractors, he was the cold engine of an administration that misled the world and left chaos in its wake. Either way, his impact was seismic. He is survived by his wife, Lynne - his high-school sweetheart - and their two daughters, Liz and Mary. Liz followed him into politics, serving as a congresswoman and, later, one of Trump’s fiercest Republican critics.