In a world where shiny AI data centers are popping up faster than affordable housing, and you can get a blueberry smoothie delivered from a robot while human delivery workers picket nearby for living wages, it’s worth asking how our systems calculate worth.

“MediaLive: Data Rich, Dirt Poor” takes that question off the balance sheet and into the art gallery, digging into what we, as a society, prize, what we overlook and how we might recalibrate.

On view at the Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art through Jan. 11, the exhibition brings together artists from across the U.S., Chile and the U.K. to probe how value gets assigned — whether to soil, servers or social systems. The works lean into what guest curator Maya Livio calls “low-tech and slow-tech” approaches, trading screen-based spectacle for tactile forms that grapple with climate, culture and community.

MediaLive is BMoCA’s flagship series on media arts. Over the years, it has stretched from experimental video and internet culture to sound, performance and interactive installation. Launched more than a decade ago as an annual festival, it now runs on a biennial schedule, each edition guided by a new curator to reimagine what media art can look like, and why it still matters in a moment where everyone’s screen time is up and attention spans are down.

For 2025, the museum tapped Livio, who teaches digital culture and technology at American University in Washington, D.C. She earned her doctorate at the University of Colorado Boulder and has long been connected to BMoCA, having curated four straight runs of MediaLive between 2016 and 2019, back when the series was still an annual event.

The theme for this year sprung from what Livio sees as a growing imbalance in contemporary culture.

“People are experiencing increased precarity, technologies are often hyper-valued, and, meanwhile, lives and livelihoods are undervalued,” she said.

That tension sharpened while she was planning the show, particularly when the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) started pulling grants it had already awarded (MediaLive, miraculously, held on to its funding).

“When visiting the exhibit, the first thing I want people to think about is that art still has meaning and value in culture,” Livio said.

That throughline cuts across wildly varied works.

“One of my orienting principles for the works in the show is that they don’t just critique problems, but actually suggest other paths,” she said.

Those paths take all kinds of forms: a speculative bureaucratic tool for climate protest by Tega Brain and Sam Lavigne, a compost-as-medium piece by Cassandra Marketos, pirate radio frequencies harnessed by Xiaowei Wang.

Walking into “Data Rich, Dirt Poor” doesn’t feel like stepping into a sterile tech expo or a server farm. Instead, the walls glow with projections that swing from hypnotic patterns of light and color to close-up footage of hands scribbling notes beside crumbling material. Oversized beanbags invite you to sink in and watch as films unspool, while in the next room, a mosquito looms across a lavender screen, magnified into something between menace and metaphor.

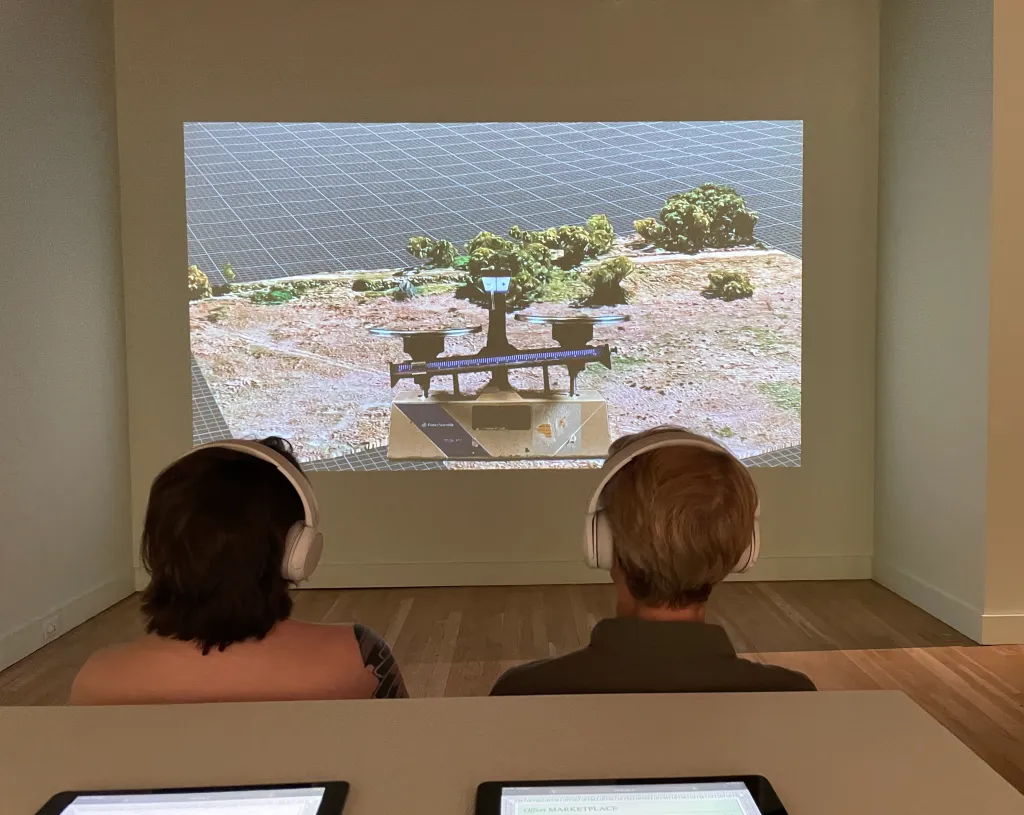

Isabel Beavers’ “Tomb Keeper” casts a kaleidoscope of electric blue and green across the wall, like stained-glass hacked by a motherboard. Nearby, Josefina Buschmann’s “Las Nubes Caídas” slows the viewer down with meditative images of fragile, cloudlike forms, equal parts geology and dream. Sarah Rara’s “Lavender House” sprawls across a long wall, pulsing with environmental unease, while Tega Brain and Sam Lavigne’s project sets viewers up in headsets, turning NOAA weather data into a strangely intimate spectacle of grids, landscapes and stormy skies.

One work emits a slow, uncanny hum — like a ghost trapped in a modem. Another invites you to observe a virtual pile of dirt long enough to start wondering if it’s whispering secrets of the world to you. Other materials used by artists in the exhibit include reclaimed metal, video, textile, sound and the kind of outdated tech that would get you laughed out of a Best Buy, but revered in a media art gallery.

Programs extend those ideas into the real world…or at least into your backyard The “CTRL+ALT+COMPOST” workshop on Oct. 23 will teach participants how to start and maintain a backyard compost system, while the “Cloudsourced” workshop on Nov. 13 invites people to intercept live NOAA satellite signals with a simple laptop and antenna. Both, Livio said, are designed to raise practical skills and bigger questions: Who has access to weather and climate data, and who gets to decide what becomes waste?

Bringing “Cloudsourced” to Boulder, she noted, made particular sense.

“Boulder is a really important site for weather data in the U.S., because NCAR is in Boulder, and so that was part of the impetus for bringing this work.”

For Livio, cuts to institutions like the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the NEA don’t just affect individual jobs, they chip away at how society makes meaning. Artists and scientists, she said, “both interpret and make meaning of the world, analyze what’s happening, and help us understand.” Without them, she added, “we might have the data, but we lose the systems of knowledge and meaning-making that help us use it.”

One of the best compliments she’s received so far is also the simplest: visitors telling her they left reminded of the importance of art.

“If that happens, then, by gosh, like I’ve more than done my job.”