Copyright thespinoff

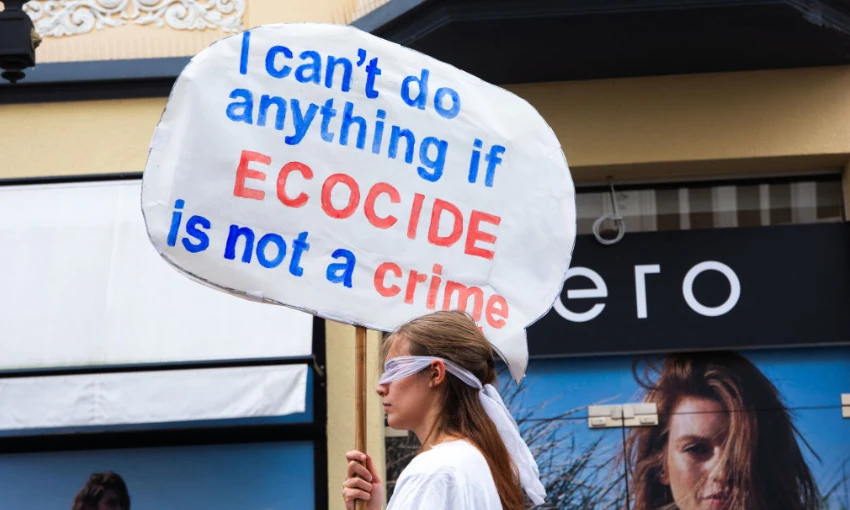

If someone were to cause harm solely to nature, but not people, New Zealand has very few legal tools available to hold them accountable, writes indigenous climate advocate Kaeden Watts. Last month, at the 2025 World Conservation Congress, the world’s largest environmental network, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), made a historic decision. The organisation’s 1,400 members voted to adopt Motion 061: “Recognising the crime of ecocide to protect nature.” The motion calls on states to enshrine ecocide as a serious crime in both national and international law. The aim of this decision was to hold individuals, governments and corporations accountable for environmental destruction on a scale so serious it can no longer be dismissed as unfortunate side effects of progress or capital gain. The motion is a watershed decision for environmental protection, and also part of a growing global movement. And while conversations around ecocide are still emerging here in Aotearoa, they’re picking up speed internationally, from courtrooms to parliaments to the International Criminal Court (ICC). The question now is not if New Zealand should engage with the idea of ecocide, but how. What is ecocide? The concept of “ecocide” has been around for about 50 years, with the term first used in 1970 by American biologist Arthur Galston in response to the massive environmental destruction caused by the US military’s use of Agent Orange during the Vietnam War. The use of the herbicide caused several serious long-term health problems, not just for human health but for environmental health also, from poisoned ecosystems to deforestation, lasting generations beyond the initial attack. For Galston, the scale of environmental harm demanded international recognition as a crime. But it wasn’t until 2021 that a formal legal definition was proposed. An independent panel of international legal experts, convened by the Stop Ecocide Foundation, defined ecocide as: “Unlawful or wanton acts committed with knowledge that there is a substantial likelihood of severe and either widespread or long-term damage to the environment being caused by those acts.” The goal of producing this definition was to propose it as an addition to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, placing environmental crimes in the same tier as crimes like genocide, aggression, war crimes and crimes against humanity. Why make ecocide a crime? One of the biggest challenges in environmental protection is accountability. Existing environmental laws often rely on regulatory fines or mitigation agreements. But these mechanisms are reactive. They tend to operate after damage is already done, and rarely act as serious deterrents, especially when the primary punishment is financial. For corporations already profiting from environmental harm, these fines are often little more than a line item. There’s also a glaring flaw in many domestic and international environmental laws: they largely only recognise harms to human health, not environmental health. That means the environment has little independent legal standing. If someone were to cause harm solely to nature, but not people, we have very few legal tools available to hold them accountable. Criminalising ecocide shifts the balance by making severe environmental harm unlawful. It creates personal and organisational liability where harm against the environment is premeditated, ensuring it is able to be legally recognised and penalised. How is ecocide being used internationally? Momentum is building. Earlier this year, Scotland introduced the Ecocide (Prevention) Bill into parliament. Spearheaded by MP Monica Lennon, the Bill would criminalise intentional or reckless acts that cause severe environmental damage. Penalties are serious: up to 20 years in prison and unlimited fines for individuals and organisations. The Bill even includes a “publicity order”, meaning those convicted must publicly acknowledge their crime; a reputational deterrent that could dissuade some companies from causing harm in the first place. If passed, Scotland would be the first UK nation to criminalise ecocide, joining at least 12 other countries, including Ukraine, the Netherlands, Argentina and France, that have either recognised ecocide in law or are actively exploring it. Some of the strongest leaders in the global movement to recognise ecocide come from our very own Pacific region. In September 2024, our Pacific neighbours Fiji, Samoa and Vanuatu jointly submitted a proposal to the ICC calling for the recognition of ecocide as a crime on par with genocide. For them, environmental destruction is not a theoretical debate; it’s an active threat. Rising seas, extreme weather and biodiversity collapse directly endangers lives, culture, sovereignty and whakapapa in the Pacific region. It’s time for New Zealand to lead New Zealand is a founding member of the Rome Statute, the treaty that established the ICC. Our legal experts helped shape its foundational texts. That history makes our current silence on ecocide all the more noticeable. But we don’t need to wait for international consensus to act. In fact, domestic law is the most powerful place to start. The ICC operates on the principle of complementarity, meaning it steps in only when national jurisdictions fail to act. That means it’s up to each country to embed ecocide into its own legal systems if we want meaningful accountability domestically. And while the ICC is a crucial backstop, we shouldn’t depend upon it to shape how we deal with environmental harm at home. The recognition of such an abstruse law may seem difficult to achieve, but we’ve already shown we can break new ground in environmental legislation. In 2014, Aotearoa became the first country in the world to grant legal personhood to a natural entity when Te Urewera Act 2014 was passed. Since then, Whanganui Awa and Taranaki Maunga have also been recognised in law as legal persons, challenging traditional legal thinking and pioneering new approaches to nature-centred jurisprudence. Many more countries including India, Canada, and Bangladesh have implemented similar legislation to protect the rights of nature, inspired by New Zealand’s model. Recognising ecocide would be a natural next step in the evolution in protecting the rights of nature. A legal tool for a planetary emergency To be clear, ecocide law alone won’t singlehandedly solve the climate crisis or reverse biodiversity loss. In fact, the concept itself is not free from critique and still has room for further development if it is to adequately protect the rights of nature, independent of human health and interests. But what it does offer is a legal tool rooted in accountability and justice. It recognises that intentional environmental destruction is deserving of serious consequences. It sends a signal that environmental harm will not be met with complacency, but instead with action. As the international tide turns, Aotearoa can choose to be idle and complacent, or we can choose to be the climate and environmental leaders we’re so often internationally recognised as. That starts with working with our Pacific neighbours, drawing on our legal whakapapa and taking principled positions for the protection of Papatūānuku, both at home and abroad. Thanks to the incredible work of Vanuatu, Fiji and Samoa in 2024, a formal proposal to the International Criminal Court to recognise ecocide has been submitted. With a concrete proposal now on the table, the diplomatic discussion is open for New Zealand to engage in. Let’s not choose to be left behind.