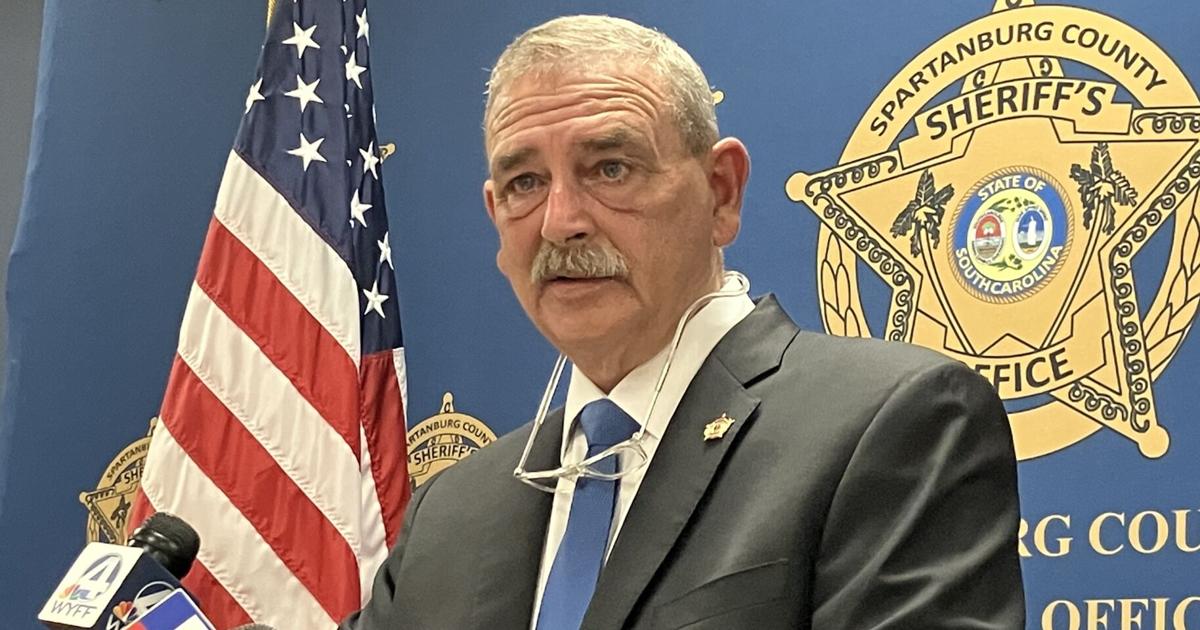

The most important thing to remember about now-former Spartanburg County Sheriff Chuck Wright isn’t that he agreed Thursday to plead guilty to three federal charges involving theft, wire fraud and illegal drugs — although that’s important.

It’s not that he hired his own son as a deputy, in what looks like a clear violation of the anti-nepotism provision in the State Ethics Act. It’s not that he made a national spectacle of himself and embarrassed our state by going up to North Carolina in the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Helene to launch a televised attack on FEMA workers who were trying to help desperately needy people.

It’s not that he hid public records about what operated like a highly organized highway robbery operation, and kept hiding those records for months after settling a lawsuit by agreeing to release them.

The most important thing to remember about Mr. Wright is that he isn’t alone. He’s the 18th S.C. sheriff who’s gotten indicted or charged with crimes since 2010; one more would have been charged if he hadn’t died first.

Perhaps you’ve forgotten some of his predecessor criminal sheriffs.

The current string started in 2010, when two-term Lee County Sheriff E.J. Melvin was indicted for turning his office into a sprawling criminal enterprise of drug dealing and fraud. He was convicted.

That same year Union County Sheriff Howard Wells was accused of concealing income from sizable loans he had made and trying to persuade the witness to lie. He was convicted.

Saluda County Sheriff Jason Booth pleaded guilty in 2012 to misconduct in office for using a prisoner to build a party shed — a scheme that inspired other sheriffs.

Abbeville County Sheriff Charles Goodwin pleaded guilty in 2013 to misconduct in office for taking kickbacks on repairs to county vehicles and using a state inmate to do work for him and his friends.

The next year Williamsburg County Sheriff Michael Johnson was convicted on federal charges that he created bogus police reports to help a friend’s credit repair business.

Also in 2014, Lexington County James Metts, then the state’s longest-serving sheriff, pleaded guilty to taking bribes to help illegal Mexican immigrants get out of jail.

And Chesterfield County Sheriff Sam Parker was convicted on public corruption charges for helping convicted inmates get out of jail in exchange for working on his house and doing other personal tasks.

In 2016, Berkeley County Sheriff Wayne DeWitt pleaded guilty to DUI, leaving the scene of an accident and failure to stop for blue lights.

Greenville County Sheriff Will Lewis was indicted in 2017 on obstruction and misconduct charges after a former assistant alleged he sexually assaulted her during a business trip; he was convicted in 2019 on one charge.

Colleton County Sheriff Andy Strickland pleaded guilty in 2020 to using his office for personal and political gain.

Florence County Sheriff Kenney Boone pleaded guilty in 2020 to domestic violence charges and in 2021 to using federal and county money on everything from bicycle equipment to window tinting.

Chester County Sheriff Al “Big A” Underwood was convicted in 2021 for lying to cover up an illegal arrest and using deputies to work on his property.

Fast forward to March of this year, and Williamsburg County Sheriff Stephen Gardner was indicted in a money-laundering scheme to funnel federal pandemic relief funds through a third party and into his personal bank account. He is awaiting trial.

And then of course there’s Mr. Wright. And whoever comes next — as someone surely will. Probably not this year. Maybe not next year, but almost certainly by the next.

This is not how government is supposed to work. Government works this way in South Carolina because we give sheriffs extraordinary power, access to largely unmonitored pots of money and no oversight except public election — which isn’t worth much if everybody who might be able to defeat them is afraid of what might happen if they run against them.

It doesn’t have to be this way.

At a minimum, our Legislature should take a few basic steps to chip away at the legal culture that tells sheriffs they’re above the law, and perhaps delay the inevitable next indictment. Lawmakers should authorize the state inspector general to investigate sheriffs, require routine outside audits of all sheriff expenditures, require sheriffs to follow state procurement regulations, give county officials clearer authority to deny sheriff’s office expenditures, and require sheriffs to post details about their spending online.

Lawmakers also should start a conversation about making sheriffs appointed positions, like police chiefs. We realize that historically speaking, that would be an extreme measure, but it seems much less extreme when it’s stacked up beside the never-ending criminality in our sheriff’s offices.

Click here for more opinion content from The Post and Courier.