Copyright Hartford Courant

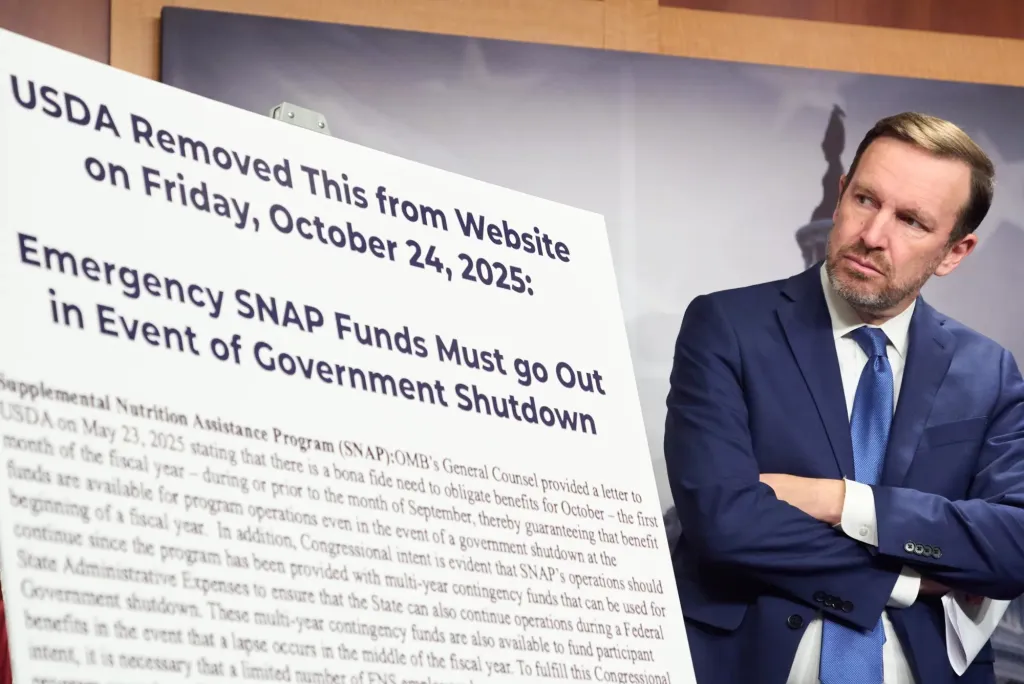

Chris Murphy was known as a lead negotiator during the Biden administration, tackling thorny political issues like gun safety and immigration. But as a group of congressional Democrats struck a bipartisan deal to end the government shutdown, the Connecticut senator was notably not involved — and openly critical of the negotiations taking place. In an interview from early 2024, as the Senate was taking a vote on an immigration bill he helped craft but that ultimately failed, Murphy said he was proud of “my developing role as a negotiator and dealmaker in the Senate.” But as the Senate took a series of votes to pass the shutdown deal on Monday night, the Connecticut senator was seeing things very differently. “I just don’t think that’s the job right now. The job is to save the democracy and that involves a lot more fighting and drawing hard lines than it does negotiating,” Murphy said in an interview near the Senate floor as lawmakers passed the government funding package Monday night. “I think there’s a danger to bipartisan dealmaking today in a world where it ends up giving some level of endorsement to [President Donald Trump’s] campaign to destroy our democracy.” “There’s still room for negotiation, but only with Republicans that are willing to actually stand in the way of his corruption,” he added. “Unfortunately, there don’t seem to be any Republicans right now that are willing to protect our democracy and thus you don’t have negotiating partners.” That’s a marked change from the past couple of years when Murphy seemed to revel in his role as a key negotiator for some of the more politically fraught issues coming before Congress. In 2022, he secured one of the biggest policy achievements of his career with the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act, which brought modest changes to gun laws after pushing for reforms for a decade. Several months after, he was part of a negotiating group on the Electoral Count Act, aimed at preventing future interference in certifying election results and avoiding a repeat of the Jan. 6 attack at the U.S. Capitol. A year later, Murphy waded into a more unconventional policy area for him when he became the lead Democrat trying to hash out a border deal to unlock support for then-President Joe Biden’s national security package. The deal seemed like it would get the backing of nearly two dozen Senate Republicans, but most of that support quickly disappeared when Trump, who was a presidential candidate at the time, came out against the bipartisan legislation. It was, as they say, a wake-up call for Murphy. “In 2022, when we negotiated the gun bill, we didn’t have to deal with Trump. It mattered what he was going to say about it, but we didn’t have to negotiate with him,” he recalled. “Now you have to negotiate directly with him. By the time we got to 2024, he was starting to take control of the party. I saw the transition.” Murphy doesn’t know how the Democratic side of the shutdown negotiating group came together, and shook his head when asked if he had been interested in getting involved. But he said he spoke with those colleagues over the past few weeks and discouraged them from making a deal that contained only a promise to vote on enhanced health care subsidies, rather than a guaranteed extension. Murphy, who became a prominent voice on gun control following the 2012 mass shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, has become even more of a national figure since last year’s election. He is frequently mentioned as a potential presidential contender in 2028 — or moving higher up the ranks of Senate leadership — and has grown into a prolific fundraiser. He has nearly $11 million in his campaign account, even though he will not need to tap into that for his own race since he’s not up for reelection until 2030. But he has more recently focused on his political action committee, American Mobilization Project. His PAC has made political contributions to some of his colleagues and other Democratic candidates, but has also contributed money to efforts and groups pushing back against the Trump administration rather than tied to an election. Some of that money has gone to organizing groups like Georgia Youth Justice Coalition for Action, Project 26 Pennsylvania, and Down Home North Carolina. His ascendance in the Democratic Party hasn’t come without sharp criticism from Republicans inside and outside of Washington. Murphy has tangled with the White House over the past year and the president himself, who has posted on his preferred social media platform, Truth Social, to take jabs at the senator. And Republicans back in his home state have also been critical of his more visible role in the Democratic Party. Connecticut Republican Party chairman Ben Proto argued Murphy’s evolving role in the party “gives him a huge platform, takes fundraising prowess to another level and gives him an opportunity to be even more hyper partisan, particularly if he’s in the minority.” House Minority Leader Vincent J. Candelora, R-North Branford, remembers his time serving in the state legislature while Murphy was a state senator. At a recent meeting speaking to Connecticut’s Young Republicans chapter, Candelora placed the blame for the shutdown on Democrats for digging in on their health care demands. And he singled out Murphy, painting his transformation as someone who has moved away from policy in pursuit of politics. “Unfortunately because we live in such a blue state, our [congressional] delegation feels that they have the ability to do that without coming to the table. And I was around and worked with Sen. Murphy at the time,” Candelora said. “I watched the evolution of an individual who used to be principled and believe in policy to evolve into a political creature that has become the fundraising machine for the Democrat Party nationally, and it’s at the expense of the state of Connecticut.” But Murphy’s frustration and criticism is not limited to Republicans. The three-term senator has become one of the most outspoken Democrats to take aim at his own party, especially when it comes to reassessing their messaging as a party after major losses in 2024 and their response to the Trump administration. That frustration was especially evident this week. Murphy and U.S. Sen. Richard Blumenthal, D-Conn., both opposed the bill that would reopen the government because it made no guarantee to extend the policy at the heart of the fight: expiring health care subsidies. Blumenthal similarly wasn’t part of the shutdown negotiating group and warned against accepting a deal that fell short on health care. Like Murphy, last week’s electoral victories bolstered his belief that Democrats should have stood firm on their demand that an extension of Affordable Care Act enhanced premium subsidies — that are set to expire at the end of the year — must be in a funding agreement. Blumenthal, who’s been involved in his own bipartisan negotiations on legislation like the Kids Online Safety Act and some of his foreign policy work, said he’s close with a few of the Democratic negotiators and had been talking to them in recent weeks throughout the shutdown. “I didn’t discourage them from talking. I would never discourage an attempt to reach a bipartisan solution, but anything that failed to adequately address health care would be a nonstarter for the caucus, and was going to be heavily criticized,” Blumenthal said. The latest rift over the shutdown deal put a spotlight back on the divisions within the Democratic Party that were brewing earlier this year. When government funding was close to running out last spring, Senate Democratic leadership faced blowback from the base for providing enough votes for Republicans to keep operations going through the fall. Murphy said he worries that Democratic defections on major pieces of legislation ultimately gives Trump more leverage and power. Democrats split on a short-term funding bill, known as a continuing resolution, twice this year. On top of that, he pointed to Democratic votes for the Laken Riley Act, which requires U.S. officials to detain any immigrant without legal status who has been arrested, charged or convicted of specific crimes, and the GENIUS Act, which regulates a type of cryptocurrency known as stablecoins. Senate Democrats didn’t get a vote on an amendment to the latter bill, which sought to block elected officials like the president from personally profiting. Trump signed both bills into law earlier this year. “I think it’s really harmful to have our party regularly split like this. This is the fourth major instance this year … where a minority of Democrats worked with Republicans to pass legislation that allows Trump to get away with a lot of corruption and illegality,” Murphy said. “At the very least, there should have been more people in that room, but we also have to find a way as a party to stop being split over and over again.” Murphy has had a long political career that began at the age of 25 when he ran for the Connecticut House of Representatives. He went on to serve in both houses of the state legislature before he unseated a Republican congresswoman in 2006. He has served in Congress ever since, moving over to the U.S. Senate after the 2012 election. Now, at the age of 52, he acknowledges the trajectory of his time in elected office and how he’s moved away from his dealmaking days from just a few years ago. “I just think 2025 is fundamentally different than any other year that I’ve been involved in politics,” Murphy said. “I think I would be committing sort of political malpractice if I was operating this year like I’ve operated in the past.” Responding to criticisms from Republicans who’ve known him for years, Murphy said he’s proud of his work with GOP lawmakers during his time in Connecticut’s General Assembly and on Capitol Hill. Yet, he’s unsure of more dealmaking in the near future. “I wish that there were more opportunities for good bipartisanship,” he said. “But right now, those avenues aren’t available.” Lisa Hagen is a reporter for the Connecticut Mirror. Copyright 2025 @ CT Mirror (ctmirror.org).