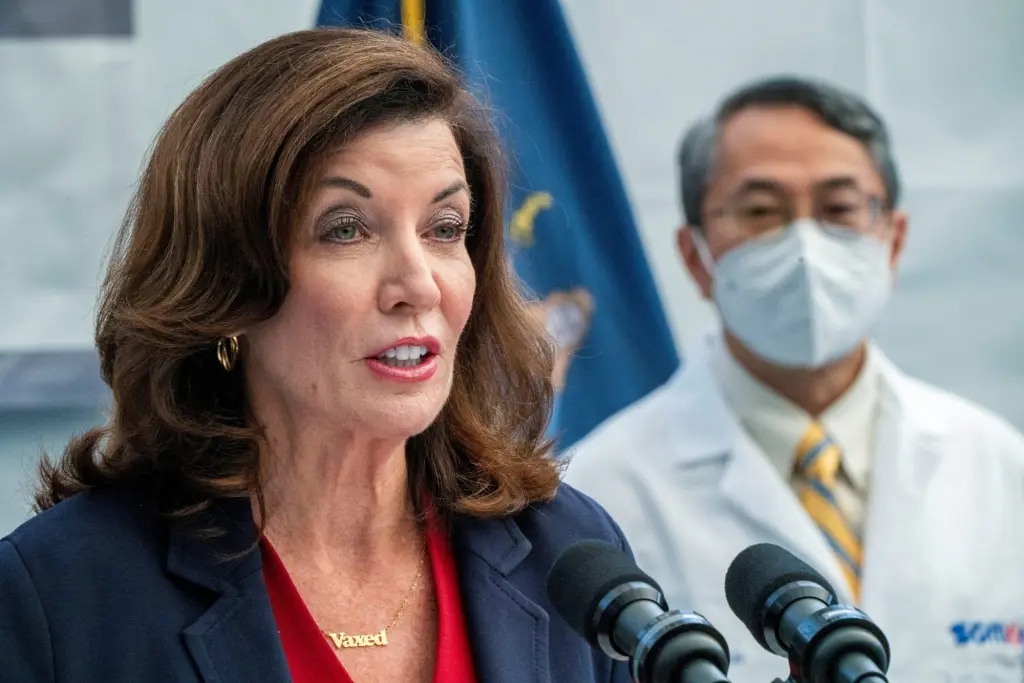

Cheer Gov. Hochul for starting to reverse New York’s tragic turn on treating major mental illness

Gov. Kathy Hochul deserves kudos for putting the brakes on New York’s decades-long experiment with deinstitutionalization of the mentally ill: She is adding beds to the state’s psychiatric hospitals.

Bravo for acknowledging reality, Governor.

Community-based treatment, supportive housing and mental health homeless shelter policies have had 70 years to prove they can work.

But the city’s streets, subways and jails remain filled with seriously sick people who desperately need real treatment.

A new report from the Manhattan Institute reveals that closing the big mental hospitals in the 1950s and ’60s and steadily eliminating psychiatric hospital beds in the following decades led to “transinstitutionalization” — meaning that those with serious mental illness wound up in other institutions, particularly prisons and jails, but also camped out in public parks or living in homeless shelters, spending their days in libraries and their nights on subway trains.

Mental hospitals were closed in reaction to lurid reports of overcrowding and poor treatment at many institutions, but shuttering them simply dumped the burden on local communities that suddenly had to dedicate resources to house, care for and sometimes jail the mentally ill.

Hochul has begun to reverse the slide by adding hundreds more hospital beds in psychiatric hospitals, but New York still has a long way to go: Mental-inpatient capacity statewide is still lower than in 2014, when Gov. Andrew Cuomo began slashing beds.

Supportive housing, which mental-health advocates and organizations push to expand, can help get mentally ill people into stable housing, but it’s not effective in treating their illnesses: Inpatient care is a far better solution for the seriously mentally ill.

Years of bitter experience prove that when no real treatment is on offer, the city’s jails and the state’s prisons become de facto mental health facilities.

Roughly 20% of Rikers detainees are seriously mentally ill. Many are jailed for committing serious crimes, but since the lockup can’t get them the treatment they need, they return to victimizing the public when released.

Taking sick people off the streets and getting them into inpatient treatment is the humane response to the mental-illness crisis.

Hochul’s reversal of the steady process of deinstitutionalization is a positive sign for New York, which can use any good news it can get.