Copyright The New York Times

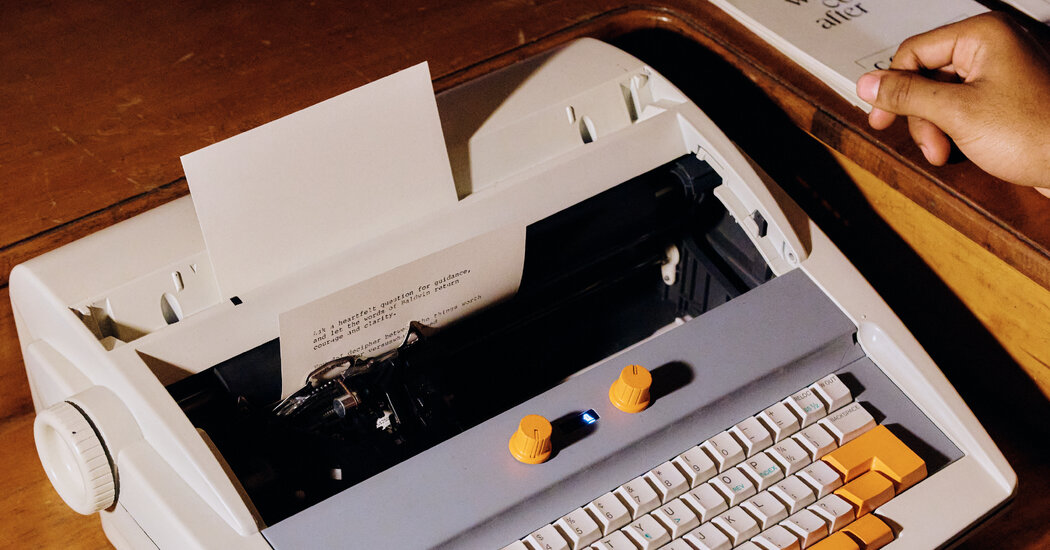

The other day I found myself sitting at a battered desk at WSA, the Manhattan financial district’s unlikely creative hub, staring at a sheet of paper in an old electric typewriter. Not just any typewriter: This one has been souped up to the point that if you type in a question, it types out a response, using artificial intelligence to direct you to relevant quotations from the work of the writer James Baldwin, one of 20th-century America’s most acute observers. I was here to experience an A.I. installation, “For Those Who Come After,” that’s focused on the words of Baldwin and produced by a Brooklyn nonprofit called Kinfolk Tech. My instructions were not to ask the typewriter about Baldwin’s life or work but to pose “a heartfelt question for guidance.” So I decided to go for broke. Channeling Camus and millions of lesser philosophers, I typed: “What is the meaning of life?” Given Baldwin’s marvelous expressions of empathy, not to mention his multiple suicide attempts, it seemed a reasonable enough question. People have been lining up for years to engage in dialogue with long-dead historic figures. In 2023, the Musée d’Orsay in Paris presented “Bonjour Vincent,” a digital incarnation of Vincent van Gogh that claimed, with limited success, to channel the thoughts of the post-Impressionist painter by way of A.I. The Metropolitan Museum of Art put an actor in a motion-capture suit and had him field questions about the Garden of Eden and the like while posing as a Renaissance statue of Adam — an even sketchier premise, since no record of the biblical first human’s opinions is known to exist. This particular typewriter sits at the end of a long corridor just beyond an arrangement of vintage living room furniture that’s grouped around an old television set on which Baldwin’s celebrated 1971 conversation with Nikki Giovanni is playing on an endless loop. The whole installation is meant to recall Baldwin’s living spaces, especially his final residence, a rambling stone house in the South of France. But his belongings have been scattered, and the house itself torn down, replaced by a luxury development. Next to the typewriter on the desk are three stacks of cards, labeled “courage,” “love” or “wisdom.” Each card has a number at the top, followed by a short quotation from Baldwin and a citation identifying its source. There’s a reason this part of the experience is so low-tech. Kinfolk Tech was inspired by A.I. chatbots from such companies as OpenAI and Anthropic. But the organization wanted to avoid the “Bonjour Vincent” approach, which involves a digital avatar saying what van Gogh might have said if he’d been a 21st-century computer program. “We are not here to zombify or bring James Baldwin back to life through A.I.,” said Idris Brewster, founder and executive director of Kinfolk Tech, which aims to surface the voices of Black, gay and other marginalized groups. “We don’t want to make up James Baldwin’s words. We want to connect you to his actual words, right? That’s a really big-deal issue with us.” The choice of medium has other advantages. “What’s cool about Kinfolk using the typewriter is that a lot of people of a younger generation wouldn’t even know how to insert the paper,” said Trevor Baldwin, the writer’s nephew and custodian of the Baldwin estate, which is working closely on the project. “So what Kinfolk is doing through the typewriter is having the user, the future Baldwinite, interact with history.” The organization teamed with the Baldwin estate and with Frank Leon Roberts, a Baldwin scholar at Amherst College, to build the digital archive that supports the installation. At the same time it built the website for Baldwin 100, last year’s celebration of the writer’s 100th birthday. But Brewster has ambitions that go well beyond typewriters. He views the WSA installation as a prototype. Early next year, Kinfolk Tech plans to release a web app that will enable users to view Baldwin quotations directly, no cards required. Eventually the idea is to use A.I. to make the work of other writers and artists of color equally accessible — a mission that’s seen by many as being in opposition to the tech industry’s race to advance A.I. no matter the consequences. “Idris Brewster should be on a stage the same way we highlight the Sam Altmans of the world,” said Michele Jawando, president of the Omidyar Network, a tech-focused philanthropy that’s one of many supporting Kinfolk Tech. Altman is the chief executive of OpenAI; Omidyar is one of 10 such organizations that make up Humanity AI, a consortium of foundations that together have pledged $500 million to ensure the technology works for humans and not the other way around. The Baldwin estate is expanding its mission as well. “We’re in the process of creating a Baldwin Justice League,” said Trevor Baldwin, “an unofficial collective of trusted writers, researchers, historians and scholars” who will build a complete digital archive of his work, his correspondence and his appearances. Their timing feels right. Baldwin’s writings on race and life seem more relevant now than ever. As Darryl Pinckney recently observed in The New York Review of Books, “people now want to know everything about James Baldwin. He has come to that.” And for good reason. When I retrieved the cards the typewriter sent me to find after I’d asked about the meaning of life, I found three aphorisms, each astute and provocative. One card, No. 3 from the “courage” stack, was particularly compelling. It was a quotation from “The Last Interview,” conducted shortly before Baldwin’s death in 1987 at the too-young age of 63: “You have to go the way your blood beats. If you don’t live the only life you have, you won’t live some other life, you won’t live any life at all.” Got it. ‘For Those Who Come After,’ part of ‘KIN: A Festival of Memory and Imagination’ Through Sunday at WSA, 161 Water Street; kinfolktech.org. At 3 p.m. on Sunday, the Baldwin scholar Frank Leon Roberts will speak with Nicholas Boggs, author of the recent biography “Baldwin: A Love Story.”